Ringling Students Are Bringing Cold Cases Back to Life Through Forensics

Image: Courtesy Photo

The bond between art and anatomy is ancient. Leonardo da Vinci once filled his notebooks with meticulous drawings of muscles, bones and the fragile scaffolding of the human face. On a campus in Sarasota, that centuries-old relationship has found a modern expression in the unlikely form of cold case investigations.

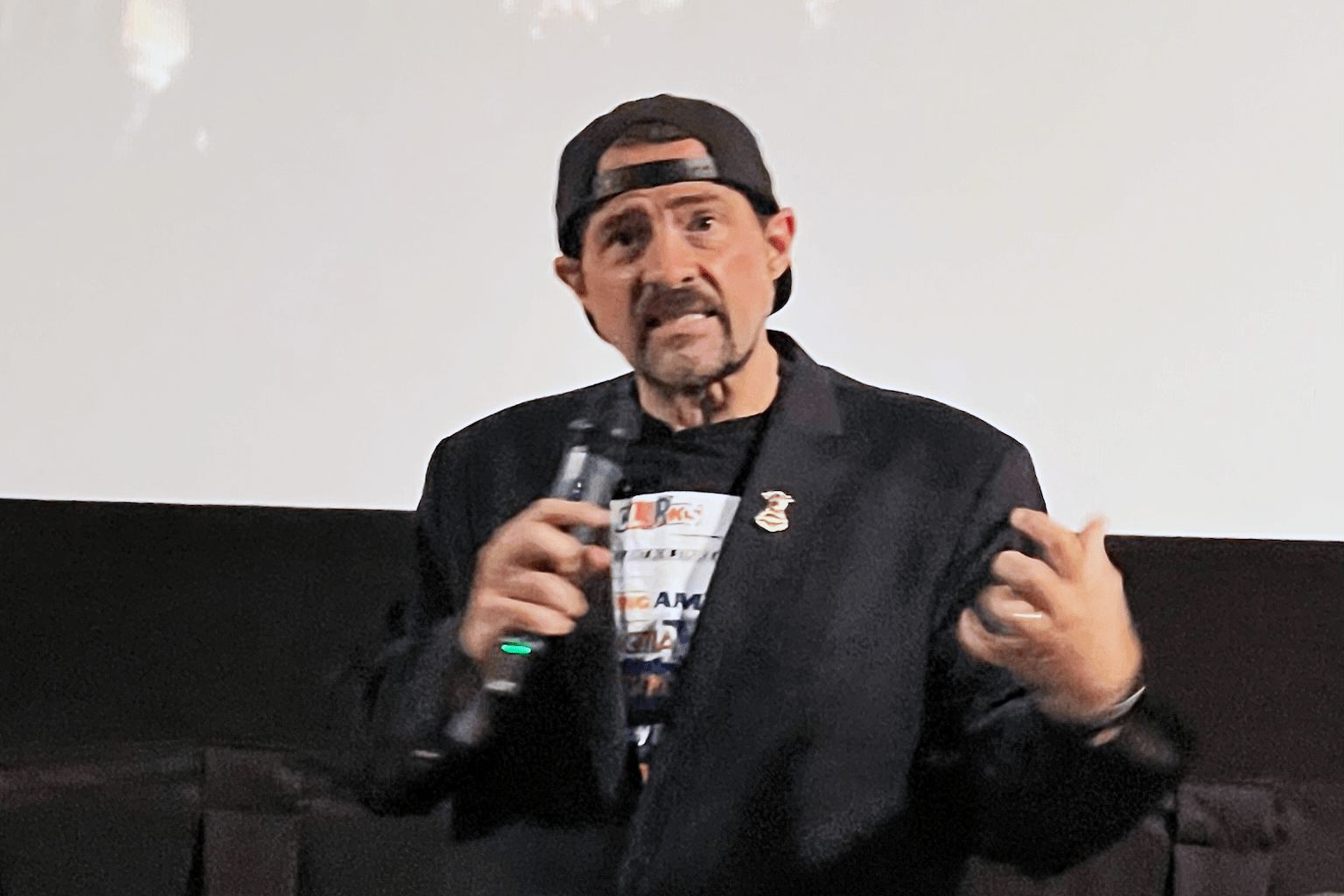

At Ringling College of Art and Design, a small but growing forensic art program is training students to reconstruct the faces of the unidentified dead. Led by veteran forensic artist Joe Mullins, the workshops are yielding not just practice, but breakthroughs in real-world criminal investigations.

“This work brings answers to questions we shouldn’t have to ask,” says Noah Shadowens, a 22-year-old Ringling graduate who never expected to be sculpting faces from the remnants of long-forgotten crime victims. Originally from Virginia, Shadowens studied illustration, arriving at Ringling with dreams of working in concept art or children’s books. But when Mullins visited the campus to give a workshop, Shadowens signed up on a whim. What followed would redirect his career—and help solve a cold case.

The workshop, now formally in its second year at Ringling, began with Mullins’ persistence. Based in Virginia, Mullins has spent more than two decades at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. His background in fine art led him into forensic work almost by accident. “A friend got a job across the street at the center, and when I visited, I saw a guy sitting with a human skull at his desk,” Mullins says. “I thought it was the coolest thing ever.”

In 2015, Mullins started teaching forensic reconstruction at the New York Academy of Art, but he wanted to expand. After speaking at PINC, an annual Sarasota event showcasing visionary speakers celebrating people, ideas, nature and community, he pitched the idea to Ringling leadership, including Jeff Schwartz, associate vice president of academic affairs. “It took a year or two,” Mullins says. “But finally, they said, ‘Let’s give it a shot.’”

Image: Courtesy Photo

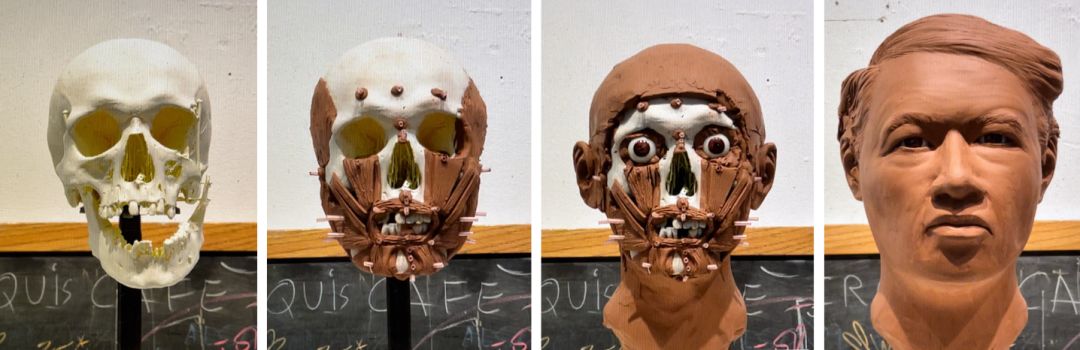

Students in Mullins’ workshop work on actual cold cases, but not with real skulls. Remains are scanned, 3D printed and prepared for students to reconstruct, layer by layer, in clay. Every measurement is dictated by anatomy and forensic standards—brow ridges, cheek contours and tissue depth markers—to millimeter precision.

“You don’t take creative liberties,” Shadowens says. “You do what the skull tells you.”

Shadowens’ second cold case tested his skills. Approximately a year beforehand, remains had been discovered in a transient encampment in Fort Myers. “I had more info: the jaw was intact, but still no teeth,” he says.

Four days after completing the clay reconstruction of the head and showing it to law enforcement, the detective involved in the case texted Shadowens. The bust had helped identify the victim as Shane Michael Williams. Shane’s brother had recognized him.

Initially treated as a “John Doe,” Williams, 39, was found in August 2024. A backpack alongside his remains contained handwritten notes that his family later recognized as his. The case is now closed, determined an accidental death with no foul play.

The bottom line is that “a family who missed and cared for him now knows what happened to him,” says Detective Rich Harasym, a cold-case and homicide investigator with the Fort Myers Police Department.

For a student project to result in a confirmed ID so quickly is rare. “At first, I couldn’t believe it,” Shadowens says. “But [the experience] doesn’t go away. It’s not like getting an A on a project. I still think about that case and that family.”

For Mullins, moments like this are the reason he teaches. “The driving force behind the workshops is to motivate the next generation,” he says. “Noah did everything right, and it worked.”

Mullins knows the emotional cost that comes with forensic work. Over his 26-year career, he has seen thousands of faces—many of them belonging to children or victims of brutal violence. “There’s an emotional gut punch,” he says. “But that fuels the path to getting it right. The family deserves answers.”

For law enforcement, forensic art remains a last resort, often called in after DNA, dental records and other databases come up empty. “We’re the last ones to get a call,” Mullins says. “This work only succeeds when the right person sees the image and recognizes it. Just because someone died in Florida doesn’t mean they’re from there.”

Nationally, thousands of cold cases remain unresolved, many with unidentified remains sitting on evidence shelves for decades. Mullins hopes programs like the one Shadowens attended at Ringling can help chip away at that backlog. “These are the coldest of cold cases,” he says. “If we can give these remains dignity and give families closure, then the work matters.”

For Shadowens, what began as an elective workshop has now become a career pursuit. He wants to give the unidentified back their names. “There are only about 200 people in the country who do this,” he says. “Now that I know it works and I can help families, I want to keep chasing that feeling.”