How Should Our Buildings Adapt to Florida's Rising Sea Levels?

Part of Florida’s inherent mythology is a world of underwater fantasy that used to be sold to tourists as an alternative reality to the miseries of Northern winters and boring, 9-to-5 jobs. The view through glass-bottomed boats, diving bells, extravagant water follies, swimming-pool balletics, alligator wrestling and dolphin shows offered a comforting kind of subaqueous suspension.

The Biltmore Hotel opened in Coral Gables in 1926 with the biggest swimming pool in the world (255 feet by 150 feet), an inland sea surrounded by Pompeii-style arcades and neoclassical statues. There were tea dances and aquatic ballets on Sunday afternoons, and people crowded around the pool to watch Esther Williams and her synchronized aquanettes.

A pre-Tarzan Johnny Weissmuller was the swimming instructor, and little Jackie Ott dove like an osprey from an 85-foot-high tower.

In the late 1930s, the town of Silver Springs promoted the charms of its crystal-clear waters by publishing photographs of a variety of events taking place underwater: men mowing the lawn, playing poker or golf; young women talking on the phone or reading the newspaper—a surreal kind of mainstream America, submerged. In 1956, Morris Lapidus, master architect of postwar Miami, designed a circular bar beneath the swimming pool of the Eden Roc Hotel with portholes so that inebriated males could watch aquatic dancers from below, half-naked, kicking and turning in the water to a musical score that couldn’t be heard.

All of these attractions seem quaintly anachronistic and politically incorrect today, but they provided a playfully erotic Atlantis in which everyday rituals—chatting on the phone, combing hair—appeared magical for being performed by pretty mermaids in slow, drifting motions. At Weeki Wachee Springs near Spring Hill, the audience sat back in comfortable amphitheater seats and watched the topsy-turvy world of aquatic wonders unfold through thick panes of tempered glass—fin-tailed beauties posing among faux ruins of a classical Roman city—and forgot all about their everyday worries.

However trivial and seemingly banal these water shows seem now, they foreshadowed another new kind of underwater realm in which actual buildings, actual cities, would one day be submerged beneath the sea, a grander, darker version of Weeki Wachee Springs.

“Goodbye, Miami,” an alarming article written by Jeff Goodell for Rolling Stone magazine (June 2013) begins by painting a scene of a partially submerged Miami circa 2030 (only 16 years from now): “A dead manatee floated in the pool where Elvis had once swam... a crocodile nested in the ruins of the Perez Art Museum...” A three-foot rise in sea level will submerge more than a third of southern Florida, according to Goodell. “If the seas rise 12 feet,” he writes, “South Florida will be little more than an isolated archipelago surrounded by abandoned buildings and crumbling overpasses.”

Florida is the flattest, lowest state in the United States and has recently become the poster child for climate change, the New Atlantis. According to experts, the region is under imminent threat, wedged as it is between the Atlantic on one side and the Gulf of Mexico on the other. (Many of Sarasota’s own iconic buildings were built on low-lying spits of sand that will most likely be the first to go.) Sugarloaf Mountain, near the town of Clermont—and hardly a mountain at 312 feet—is considered the highest point, but much of the state, especially around Miami, lies less than five feet above sea level.

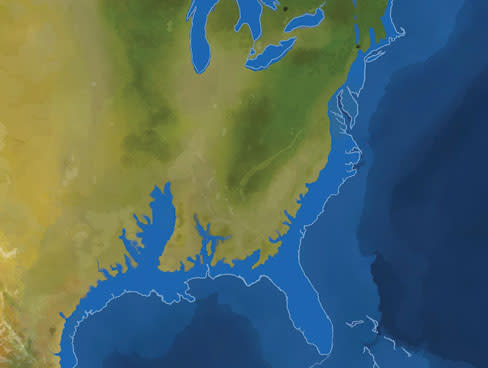

A map recently published by National Geographic shows what North America might look like after the polar ice caps have melted. Coastal areas along the east coast will be entirely underwater and Florida—the entire peninsula, including Sugarloaf—is not even on the map.

“Miami, as we know it today, is doomed,” says Harold Wanless, chairman of the department of geological sciences at University of Miami. “It’s not a question of if. It’s a question of when.” Wanless and other scientists predict that by 2030, the sea may have risen more than two feet and as much as six feet by 2100.

“This is ground zero for sea-level rise,” warned U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson, who hosted a hearing in Miami Beach on Earth Day last April. More than $1.5 billion has already been allocated for projects designed to hold back the rising tides. Dutch flood experts have been flown in to consult on the matter, and Broward County enacted a climate change master plan, but all of this may be in vain, a case of too little, too late.

Despite the dire predictions, investors and developers in Miami and other coastal cities seem to have missed the memo. With speedy profits in mind, they’ve been lulled into mass denial and continue to build higher and more elaborate structures in a place that may, one day, be a sunken city. Instead of sober resolve, there’s an intoxicated, end-of-the-world giddiness to new development that, regrettably, matches the area’s stereotypical image of sybaritic excess. Party hard and live for today! Forget about the drowning future. Miami Goes Wild, reads the wet T-shirt of today. Of course, it doesn’t help that many of the state’s political leaders—including Gov. Rick Scott, Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio and former Gov. Jeb Bush—continue to insist that climate change is a myth conjured up by a liberal conspiracy.

Money speaks louder than scientific fact. Real estate is booming. Wildcat investments are pouring in from South America, Europe, Russia and the Far East. Virtually every block along Miami Beach has a new project under construction, and the skyline of downtown Miami bristles with glassy new high-rise buildings that appear to have been dropped into place like so many alien entities. Architecture with a capital “A” is exploited as a mighty marketing tool, with riotous forms and oversized balconies that expand giddily into fleckless blue skies.

As Miami rises higher, the city continues to sink at alarming rates. On any given day, you can find areas that are already under water, depending on the tide and lunar cycle. Sub-level garages and residential basements are regularly flooded. Fresh water is being contaminated as sewage gets displaced by seawater. Storm drains are overflowing and can’t handle the saltwater that bubbles up through the porous limestone aquifer. During the full moon, small rain puddles expand into lagoons that stretch along the lower sections of Alton Road while the undercarriages of Bentleys and Maseratis corrode in the brackish soup.

Over the past few years, an A-list of star architects descended upon Miami, offering oddly pale and bone-like monuments to the doomed city, such as the 60-story “exoskeleton” tower by Zaha Hadid; a luxury condo tower by Sir Norman Foster; glass cubes with breakaway walls by Richard Meier (at the Surf Club); twin towers—something like dueling tornados—in Coconut Grove by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels—to name a few high-profile projects.

The old Miami Herald building was recently demolished to make way for Resorts World’s $3.1-billion “city-within-a-city” (by Miami-based Architectonica), and pushes the denial to an even grander, more ludicrous scale. The Malaysian-backed project is being built right on the city’s endangered waterfront and features blob-like forms that appear hyperinflated with helium. It’s all beginning to feel spookily like a Pompeian bacchanal.

Presented as they are in CAD (Computer Animated Design), so many of these proposed structures have an overlit, airless quality. In a CAD rendering for one new tower, a single heroic figure wearing a white linen suit stands in silhouette on a cantilevered balcony, sipping a mojito and watching the sunset over Biscayne Bay. He is the Architect, the new Howard Roark, oblivious and unaware of the rising waters and social unrest brewing down below. Within this sunny, plenoptic Fountainhead, the moody charcoal chiaroscuro that Hugh Ferriss popularized in his Depression-era renderings of a future New York has been replaced by a shadowless empire awash in waves of translucent blue pixels.

Instead of denial or full-scale panic, architects, developers, environmental and urban planners, scientists and, yes, poets need to be looking for solutions that are both practically and metaphorically viable. (Unfortunately, without the right set of metaphors, true change is impossible.)

There are a few architectural exceptions to the rule, one being the recently opened Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), in which the Swiss firm of Herzog & De Mueron managed to create an inspiring civic space while acknowledging the city’s precarious narrative with low-key design based in part on environmental conditions—hurricane winds, flood, climate change—and paying homage to both the human culture and natural ecology of

the place.

I grew up on the eastern shores of Long Island, N.Y., a low-lying sandy area (not unlike Sarasota) that became known in the postwar era for its radical artists (Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, etc.) and experimental architecture. My first book, Weekend Utopia, was a personalized survey of escape houses built during the 1950s and 1960s by architects such as Peter Blake, Andrew Geller, Tony Smith and George Nelson. Their designs were highly sculptural and often whimsical in form, but were small, inexpensive and easy to maintain—unlike so many of the trophy houses built in recent years by New York billionaires.

The earlier houses—tiny in comparison, often less than 1,000 square feet in plan—provided simple summer pleasures: a direct connection with the sea and sky, large sun decks, bunk beds, outdoor showers, swimming, beach picnics and a kind of family unity that came from sharing small spaces. The houses stood out boldly on their waterfront sites, perched high enough on locust posts to withstand hurricanes, Nor’easters and seasonal flooding. Their footprints took up only a fraction of the designated building lot. For me, these all seemed like basic truths that could be applied to a broader kind of sustainable architecture.

Raising the bar for all of Florida, the 120,000-square-foot Perez Art Museum hovers lightly above Biscayne Bay with a humility that is uncharacteristic for this city of architectural hubris.

Early proposals showed pyramidal forms with stacked slabs rising vertically, as if to compete with the skyscrapers of downtown Miami, but such temptations were resisted by the architects; and the end result is an airy assemblage of screens, slender columns, scrims and cubic volumes (containing art galleries) that float between a wooden roof “trellis” above and cantilevered terraces below.

“Museums work better when they’re horizontal,” says Jacques Herzog, who makes it a practice to immerse himself in the context of every site he works on, conducting in-depth research into historic and environmental conditions. In this case, he studied South Florida’s vegetation as well as local building styles, and found inspiration in mangrove swamps and how the mangrove plants were able to grow in salt water, a fitting reference for a waterside museum. He also discovered Stiltsville, a unique little community of self-built bungalows that sit high on wooden pylons in the middle of Biscayne Bay. Stiltsville became a touchstone and operative metaphor throughout the design process: simple, indigenous forms rising cautiously above the water.

Cast concrete forms are complemented by a series of hanging “gardens” that surround the museum, dangling from the roof like ropes of Spanish moss or the air roots of a banyan tree. Columns and peripheral plantings were designed by French garden artist Patrick Blanc, who used 54,700 plants and 77 local species, including an exotic mix of salvia, parlor palms, begonia and silver-leafed Artemisia, all lushly sprouting so that the museum begins to resemble an overgrown ruin, a kind of monumental chia pet with multiple trunks and dangling air roots. All parts of the facility were designed to withstand Category 4 hurricanes and severe, 100-year flooding.

The museum doesn’t scream out for attention like so many other recent buildings. From the water it almost disappears, blending into its setting without disrupting the messy urban vitality and natural beauty of the site at the intersection of Northeast 11th Street, Biscayne Boulevard and the MacArthur Causeway. The sea-flecked light is voluptuous, sparkling, almost iridescent with inlets and ocean on one side, skyscrapers and sprawling urban infrastructure on the other, at the very crux of a convergence between nature and commerce, and the architecture seems just right: subtle and porous but distinct in character while accommodating a wildly uncertain future. Cars and people movers whiz past; cruise ships come and go through Government Cut; tankers unload at the adjacent Port of Miami; and jetliners stream overhead, making their final descent into Miami International.

Alastair Gordon, a contributing editor for architecture and design at WSJ, the Wall Street Journal magazine, also publishes the Wall-to-Wall blog. An award-winning author, critic, curator and filmmaker, he will be a featured speaker at the SarasotaMOD weekend taking place Oct. 9-12.

This article appears in the October 2014 issue of Sarasota Magazine. Click here to subscribe. >>