Sarasota Author John D. MacDonald is Back in the Spotlight

When John D. MacDonald died in December of 1986, I called up the editor of The New York Times Book Review—for whom I had been writing reviews and essays—and asked if they wanted a short piece about him. I had gotten to know him pretty well during the last several years of his life.

There was a long pause from the other end of the phone. The audio equivalent of a blank stare. “No,” the editor finally said. “Why would we want that?”

“Because he was a great writer,” I wanted to yell back. But I kept my mouth shut, thinking, just wait, you’ll see.

***

At the time of his death—a little premature, as he was only 70—JDM was considered one of the country’s best mystery writers. But that only took you so far back in those days. Real writers were people like Saul Bellow and John Updike. How seriously could you take a mystery writer, particularly one who wrote about Florida? It’s been a while, but these days “John D.”—as many people in Sarasota still refer to him—is finally being recognized as not just a great writer, but one of the most important of his time, his time being the latter half of the 20th century. He perfected a genre—the thriller anchored by a complex antihero—and turned it into the genre of our time. Just look at the best seller list. John Grisham. Michael Connelly. Carl Hiaasen. And Stephen King, who has called John D. “the great entertainer of our age.”

His books were latecomers to electronic publishing—there was some problem with the rights—but have lately been selling so well that his son and heir, Maynard—who lives in New Zealand, of all places—has become a wealthy man. And now there’s Hollywood. Rumors of a big-budget version of The Deep Blue Good-by fill the Hollywood trades, with a major star playing Travis McGee. There is even talk about a “franchise.”

I can’t think of franchises in the works for Rabbit Run or The Adventures of Augie March. John D.’s “competitors” in the Important Writer category are fading fast into, if not obscurity, at least that part of academia that archives and preserves things. Whereas John is the toast of hip young Hollywood. Would he have been surprised? Absolutely not. He knew exactly what he was doing, and how good it was, and how good he was at doing it.

***

John D. moved to Sarasota just after World War II when he got out of the Army. He found himself part of a group of like-minded writers, artists, and architects who formed what came to be known as an artists’ colony. He and his wife, Dorothy, settled on Siesta Key, and the key became his home for the rest of his life.

His house is still there, the one he built in the mid-1960s when he started making decent money. It overlooks New Pass and was designed by his good friend, architect Tim Seibert, and it is both simple and sophisticated. The primary concerns seem to be security and privacy.

The MacDonalds were beginning to have problems with overzealous fans ringing the doorbell of their first home on Point Crisp, so the new one was tucked away on a dead-end street, behind a gate. It was fortress-like in its construction, with pillars going right to the limestone, and was designed to withstand the strongest hurricanes. Although even it would have been destroyed by the one John dreamed up for Condominium, the 1975 best seller that ought to be required reading for every newcomer to town.

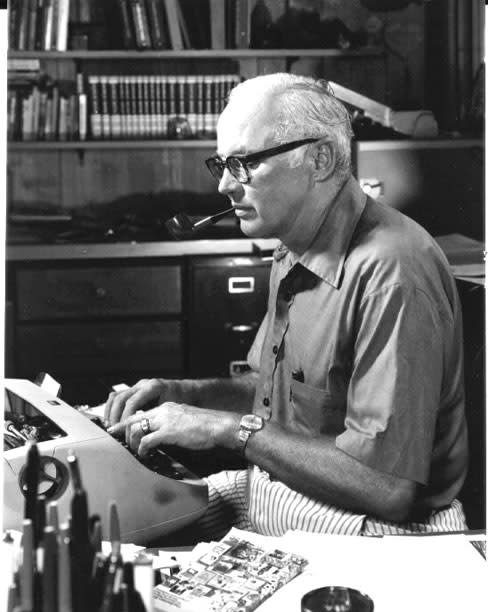

John and Dorothy had refined but unpretentious taste. The home, famous for having only one bedroom so houseguests wouldn’t be an issue, was in the style of the time, rather sparsely furnished with well-designed modernist furniture—nothing antique, no family heirlooms, and everything suitable for Florida beach living. John worked in his office on the top floor, although he faced away from the view so he could concentrate better.

Dorothy was a serious amateur painter, a member of a group called the Petticoat Painters, and her canvases covered the walls. And I mean covered—there were scores of them. They were mostly abstracts, well-composed and well-executed but lacking the spark of true creative talent. I still own three of them. Only one really hits the mark, but, oddly enough, it’s the least successful one that I cherish most of all.

Back in the 1960s and ’70s the MacDonalds were very much a part of the town. They were charter members of the Field Club. He was one of the founders of New College, he was on the board of a local bank, and he pushed environmental causes, an almost unheard-of quirk back in those days. They went to all the parties, the dances at the Sarasota Yacht Club as well as the more bohemian affairs with too much drinking at MacKinlay Kantor’s, Sarasota’s other famous writer at the time. Kantor, in his heyday, was the more well-known and revered of the two, a “real” writer of serious novels who has, alas, slipped into obscurity.

If you read the Travis McGee books carefully, you’ll find all sorts of allusions to the Sarasota of those days. Travis wears a Hagar the Horrible wristwatch, a tribute to John’s friend, Dik Browne, who created the comic strip. An even more important friendship was with Syd Solomon, the painter. Syd, who is now recognized as one of the great colorists of the abstract expressionist generation, helped John come up with the famous color-referencing titles of the Travis McGee series. This accounts for the wallop each title packs—they are all a color poetically distilled to its essence, only in words: The Deep Blue Good-by, Nightmare in Pink, Free Fall in Crimson, Darker Than Amber…

John returned the favor by putting a Syd Solomon painting on Travis’s famous houseboat, The Busted Flush. It’s rather small, 12 inches by 16 inches, and is screwed to the bulkhead. In The Lonely Silver Rain, it gets splattered with blood.

Was Travis John D.? Absolutely not, although they did have much in common. There is a dignified unflappability about both men. You can’t picture either one uncertain or flustered about what to do next. They both had a hard, cynical streak, but it was redeemed by a compulsion to right wrongs and protect the weak. Both were generally kindhearted, but both could be withering and abrupt about people who were behaving foolishly—or in John’s case, writing foolishly.

The unsettled question that fans debate endlessly concerns Travis and women. Was he condescending to them? Did he take advantage of their vulnerabilities? He was certainly unwilling to commit. But was this a character flaw or a statement John was making about the human condition?

And that may be the biggest difference. Travis was a loner. John had a wife and partner. Maybe up in his study he imagined himself doing all those things, but when he came downstairs for lunch he was very much a married man.

But the main thing that Travis and John D. had in common was their love for Florida. John left Sarasota in September 1986 to journey to the Mayo Clinic for open-heart surgery. It was hardly routine, but still, thousands of people did it successfully. Just before he left he told me that the mortality rate was 6 to 8 percent. He certainly didn’t seem very worried. “Pretty good odds,” he said.

But things didn’t go well. There were complications, and pneumonia developed and he kept getting worse and worse. For almost three months he lingered in the hospital as a Northern winter set in. Just before he slipped into his final coma, he looked up at Dorothy and managed to get out one word: “Home.” It was the last thing he ever said.