Mote Scientists Dive Into the Green Banana, One of the World’s Deep Blue Holes

On Aug. 31, a team of Mote Marine Laboratory scientists, investigators and volunteers boarded two research vessels on City Island and headed into the Gulf of Mexico about 50 miles west of Sarasota. It was a blustery day, not exactly perfect for boating or diving, and by the time the boats had reached their destination two and a half hours later, Mote’s Dr. Emily Hall was seasick. But that didn’t dampen her enthusiasm. Hall is the principal investigator of the Green Banana Expedition, an exploration of one of the deepest blue holes found in the Gulf or perhaps the world.

Blue holes are marine caverns. The Gulf of Mexico is filled with dozens of them; experts believe they may have been sinkholes formed 12,000 years ago when Florida’s coastline extended another 100 miles into the Gulf. These dark holes are difficult to find and explore because their openings can be deep below the surface of the water and the openings and passageways are often narrow, making it difficult—and scary—to squeeze people and equipment through.

The Green Banana was discovered by fishermen decades ago and was supposedly named for a green banana peel bobbing over the opening. Shaped like an hourglass, the hole starts about 150 feet below the surface and goes down to a 425-foot depth. Intrepid technical divers have managed to reach the bottom, but the Green Banana had never been explored scientifically until this summer.

Dr. Emily Hall taking measurements of Green Banana.

Image: Kristin Paterakis

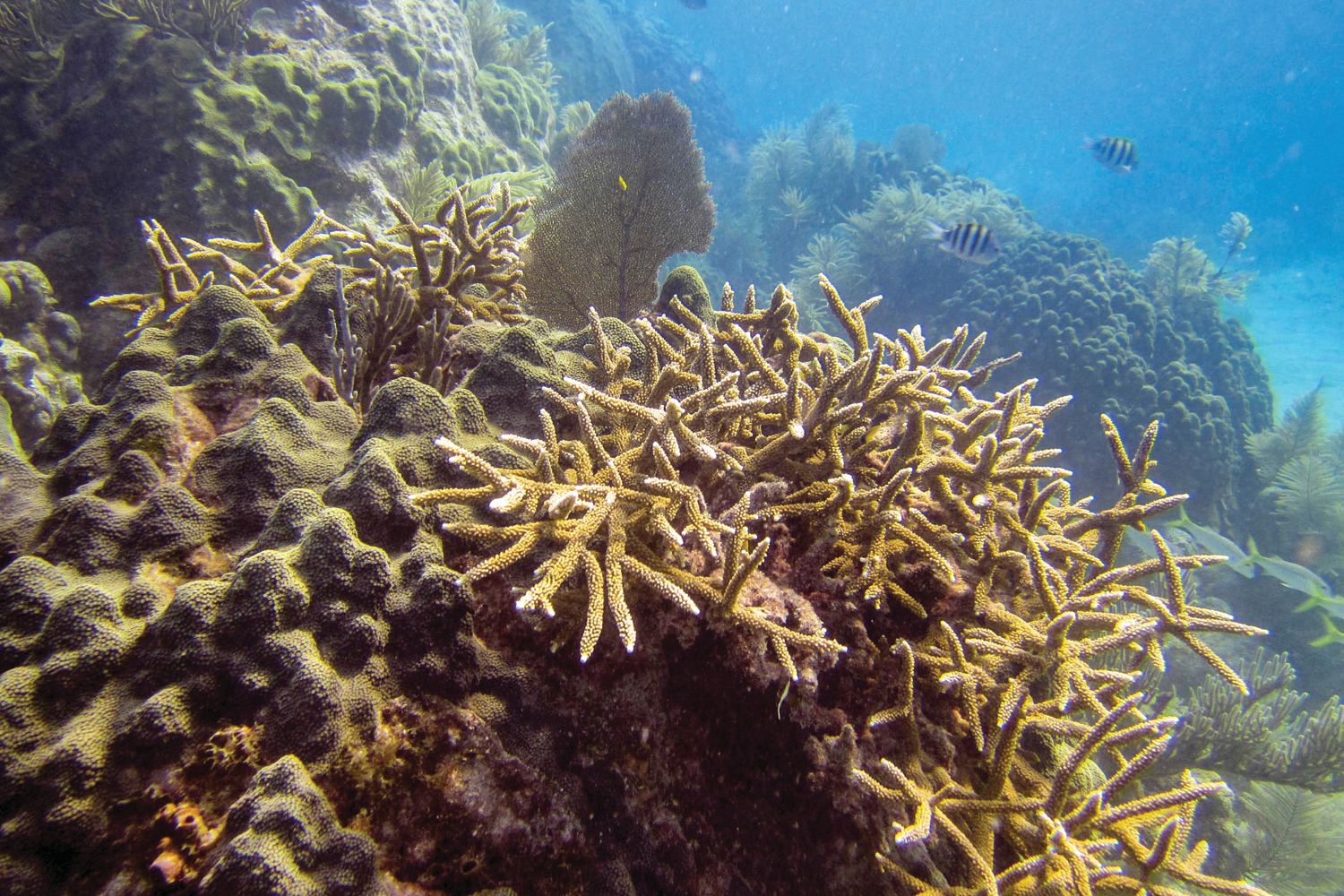

For Hall, a Ph.D. marine chemist, exploring Green Banana is as thrilling and groundbreaking as “exploring another planet.” Scientists—and commercial fishers—have noticed that an abundance of fish congregate around these holes, and they don’t know why. “The Gulf looks fairly empty and then you come to the hole and it’s teeming with life,” Hall says. “It’s a biological hot spot.”

The research crew sent down a benthic lander, a 600-pound instrument—“like the moon lander,” Hall says—to collect sediment, seawater and marine life. Hall dove to 160 feet, which requires special training, to take measurements of the hole opening, but diving another 250 feet to get to the bottom had to be done by a team of technical divers who have additional skills and specialized equipment, including a mixture of three gases in five tanks to descend and come back up again. Mote scientist, cave diver and blue hole explorer Jim Culter and several volunteer technical divers suited up and slowly made their way to the sea floor 425 feet below, spending about three hours in the water to explore and take samples.

The data from the five-day expedition, supported by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant and including scientists from Florida Atlantic University, Georgia Tech and the U.S. Geological Survey, is still being analyzed.

A team of Mote researchers and volunteer divers prepares to enter the water.

Image: Kristin Paterakis

For Hall, the Green Banana, and the blue holes scattered throughout the Gulf, are filled with mysteries about our marine environment. “There are so many unknowable things,” she says. “It’s like sending people into space.” We know more about the surface of Mars and the moon than we do the ocean seafloor, she says. What organisms live there? Is the water salinity unique? Perhaps the Green Banana and a network of blue holes connect to the aquifer on land. Could they be a source of saltwater intrusion or, is freshwater filled with natural and manmade nutrients flowing into the Gulf, potentially fueling red tide?

Hall is already thinking about these questions for her next trip this spring. The exploration could provide insight into our future, unique habitats and changing climate, she says. “The findings might provide incentives to protect our environment,” she says. “We just don’t know yet.”

For more about these blue holes in the Gulf of Mexico, watch Florida’s Blue Holes: Oases in the Sea, part of the public television series Changing Seas. The writer and producer, Kristin Paterakis, was a diver and photographer for the Green Banana Expedition.

Mote will be updating information from the expedition in a blog on its website.