Saranova and Me

Sarasota is a city of easygoing charm and civility. Champagne-toned convertibles smooth down streets at five miles an hour under the limit. Lines in grocery stores and movie theaters are devoid of jousting. Even in the most popular restaurants the crowds are mannerly, and negotiations on pedestrian walkways are, by and large, benevolent. I have had conversations with Sarasotans about lawn bowling, philately, the role of caviar on deviled eggs, the reddish egret, innumerable kinds of medications and vitamin therapies, the comparative merits of sundry brands of mobility scooters, kids today. At Pastry Art and Owen's Fish Camp and the Bikram studio, I often feel like a celebrity just for being young. And because whenever I am lucky enough to visit I am usually safe at home by 10 p.m., this is what I know of the city.

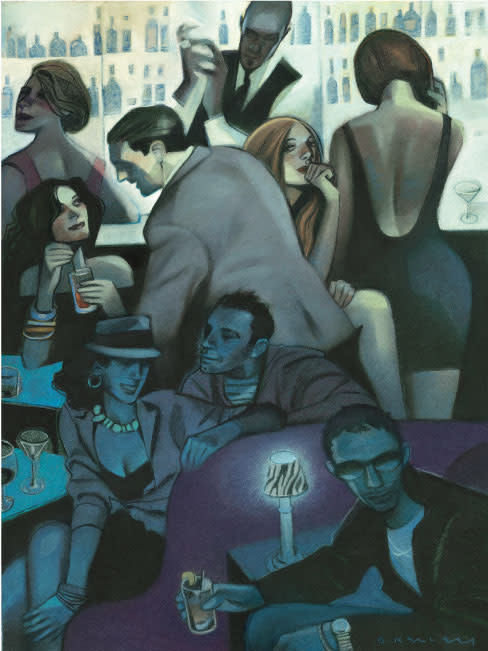

But there is another Sarasota, an after-hours Narnia of barroom striving, romantic collisions, of intrigue being engineered and shots being shot—of things happening. And tonight, more than any other night, things will happen, because in one hour I am meeting up with SRQ's most accomplished, most notorious Casanova—lets call him "Saranova"—and he is taking me behind the velvet ropes and into the rabble-rousing world of late-night Sarasota.

Here we go.

5:15 p.m. I am sitting by myself at the bar in Selva on Main Street—my favorite restaurant in town—an hour before Saranova is due, because it seemed prudent to have a solitary drink, like an athlete's pre-game stretch, before he shows up. At this time of day there is a ritualized quiet to a restaurant like Selva. The barback is busy with prep work, parceling lemons and stocking bottles and refilling the bev nap holsters. There is the whine of the receipt machine, the vacuum-packed thwump of plastic containers opening, the whap of the seal breaking on a new jar of olives, the susurrus of juices being poured into pitchers. It's all routinized, formal. Bars court chaos, invite it. That is their mandate: They are the redoubts of chance, the who-knows headquarters. In bars, you can meet anyone, and anything can happen. And this is how they prepare for it and make it possible.

Watching it unfold gives me a good, clean, backstage kind of feeling.

5:30 p.m. The TVs are on mute and the music is so low it's nearly subliminal, but the prep work is done and the place is warming up with bodies. Now the bartender will listen to your story of the best barbecue joint in St. Louis. Now he will nod sagely at your choice of exclusive hotel. In half an hour, he won't, because, as the bartender tells me, "In restaurants, 6:30 to 8:30 is the hell-time."

In the meantime, though, I have time to reflect on Saranova.

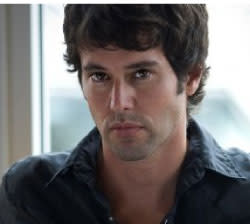

Who is he? Well, he is in his late 30s or early 40s—which he hails as the "sweet spot," an age at which one can bed women "anywhere on the age spectrum between the barely legal and the barely continent"—but other than that there aren't any of the usual flagrant signals of ladykilling know-how. He is wealthy, certainly, and constantly engaged in some kind of thrilling entrepreneurial daredeviltry—he is, this very week, in the process of buying a telecom company, which he mentions to me in the offhand manner of someone who's decided to adopt a kitten—but he isn't classically handsome, and he isn't a peacock. He doesn't have hulking shoulders or cably forearms or large, powerful, face-cradling hands. He does not have sculpted hair or gleaming amphitheatrical teeth. And although he dates musicians and ballerinas and actresses and models, he does not evince any world-class expertise in music, or ballet, or film, or fashion. And his hair? Receding. Complexion? Gluey. Abs? Well, let's just say they aren't exactly ...topographical.

So how does he do it?

He has got charisma, all right, and determination, and an indomitable confidence and barroom élan. He doesn't just patronize bars; he absolutely pollinates them. He is always sending over drinks or striking up conversations with ladies unknown. Every bouncer in town waves him in, every bartender knows his drink, all the cocktail waitresses wink or—if they have an uncharitable opinion of him, which, Saranova concedes, is an avocational hazard—roll their eyes. When he goes out, it's not to just one spot. He bounds and rebounds around the city, from bar to strip joint to club to apartment and back out. He is supremely indefatigable.

But none of this offers a comprehensive explanation of Saranova's success. More than anything it seems like he is simply a miracle of some kind of natural selection—birds fly, snakes slither, Saranova flirts.

He can't help it, and he can't stop.

6:30 p.m. Right on cue, Selva swells with customers. Diners and drinkers materialize on bar stools like genies. The single lady next to me who had been fidgety and anxious while sitting alone opens up like a blossom when her friends arrive. Servers are friendlier and nod more easily, performing pardon-me veronicas around six-tops before they chug into the kitchen past heavily laden coworkers with the mindless confidence of a Greek cabbie. This is their time. This is when their entire bodies become fluent. It's as if a curtain has been raised, a spotlight lit, and now they are on.

If you want dinner theater, hit Selva at hell-time.

6:40 p.m. Saranova shows up and whisks me into his Mercedes. In the front seat he has a drink waiting for me, which I half-expected, but in the back seat is something truly astonishing: a woman he introduces as his "live-in," Betsy.

Betsy and I regard each other warily. It turns out that today is Saranova's birthday, and I can tell that to Betsy I'm an interloper who has relegated her to the back seat and who will, at some point later tonight, take her man away from her and into unknown backrooms made foggy by cocktail fumes and cropdusterings of perfume. To me, however, Betsy is an impediment to the expected bacchanalia and, possibly, to the life of this article itself.

I grimace at Betsy. She grimaces at me.

It's a bad start.

7:00 p.m. After some GPS difficulties we arrive at the Tarpon Pointe Grill in "Bradentucky," Saranova says, to make an appearance at a surprise party for one of his friends. The place is an airy waterside joint that is populated by good-time drinkers, chain smokers, and people in motorcycle- and fishing-themed apparel. Everywhere Saranova goes he is hailed like some kind of favored Mafia don, and while he is receiving tribute from the crowd Betsy and I are left to our own devices.

In the car Saranova said that Betsy looked like Jackie O, and as she stands with me now I see that he is at least partially right. She has the same delicate features, the tractor-beam eyes, and she is statuesque, so tall in her skyscraping heels that when she turns around suddenly and bumps into me it looks like I'm performing CPR on her collarbone. But there are differences. Instead of Chanel suits and ovoid sunglasses she is dressed in a quantity of clothing that would barely cover a Pekingese—the aesthetic is less Cape Cod yacht club than South Beach nightclub—and her outfit is so tight it's as if every convexity of her body is nursing a dire and longstanding personal grudge against spandex and must punish it.

Or escape it.

And that's not necessarily bad news, because good God is she lovely. Blond, athletic, poised, feet together, knees together, back straight. Soldierly. Ladylike. And she has cheekbones that look like they have their genetic origins somewhere in Monaco or the court of the Sun King. She is also very watchful, nearly surveillant; she knows where Saranova is at all times, but she is, so far, and quite remarkably, not at all possess-ive or jealous.

7:45 p.m. Saranova has been straight with Betsy about the arc of the evening—the three of us will engage in some PG merriment until a certain hour, at which point he and I will split apart and have our own night of intrigue and roguery, an arrangement that Betsy, creditably, has accepted with grace—and so, at the moment, he is still operating at auxiliary power. People come by to say hi and to shake his hand—in thanks for helping them make a business connection, for the start-up money he invested in their company, for getting them those hot tickets, or on the guest list or backstage or laid. There is something lordly about it, almost medieval. It is like some kind of man-fealty.

Saranova just aw-shucks and buys them another drink. And let me tell you something important about this: It is sincere. He is not a sex con man. Sure, he adores women in a deep and helpless and glandular way, and he follows their movements so avidly that it's a wonder his eyeballs don't collide so powerfully with the inside of his skull that it routinely knocks him unconscious. His phone is a virtual library of photos of different women in strikingly intimate poses. But Saranova genuinely cares about people and is full of largesse. He is an investor not just in businesses but in people. He is charitable and interested and encouraging and as I stand by myself out on the deck alongside the water, getting some fresh air and trying to regain some equilibrium, I find myself thinking, very strangely indeed: Saranova would be a very good father.

8:45 p.m. Time to go. For Saranova, leaving a bar is like trying to extricate himself from quicksand, but finally his court disperses and we make it out the door, at which point I see that a mystery valet has brought his car around for us and it is now sitting there, idling with the doors open, as if the Secret Service were about to receive some diplomat.

As we approach the car we pass a shuttle bus that has been rented for the birthday girl. For a moment the door opens as drunken partygoers pile in and I see that the interior is equipped with bordello-red carpeting and a stripper pole. As a woman leaps onto it Spidermannishly, the double doors clap shut, muffling the sounds of wild cheering and, one femtosecond later, the whump of 150 drunken pounds crashing onto the floor. Betsy shoots me a look—she doesn't like where this evening is going already—and I goggle my eyes sympathetically.

Now I'm no longer an interloper. I might even be an ally.

9-11 p.m. These are the threshold hours in downtown Sarasota. The last of the older couples are closing down their tabs, the happy-hour drinkers from nearby offices and other miscellaneous holdouts start staggering homeward, and the bars begin to be overtaken by the youngest and most determined drinkers—the live-music listeners and fight-prone pool shooters and strip-club aficionados; the roving packs of tourists, both foreign and domestic; the lifer alcoholics who have been entrenched on their barstools since 5, gnashing their teeth as crowds of revelers multiply around them like a supervirus; a small culture of underage Ringling kids with convincing IDs; the early-cut busboys and servers waiting for their on-shift pals to join them; the jealous and watchful girlfriends of guys in the band and boyfriends of bartendresses; the singles and scammers and hopefuls and lonelyhearts.

This is when Sarasota becomes theirs.

In Selva, sweaters come off shoulders. Men get handsy. Cell phones make the bar and its recesses scintillate like clusters of Christmas lights. Steve, the lead bartender and a man who never forgets a drink, comes into his own, fulgurated to life by the hivelike activity of the bar and the crush of bodies. Saranova feels it too, and starts bristling with testosteronic energy. He has the trapped frenetic eagerness of a sled dog ready to run.

The undertow of the bar has pulled Betsy away from us for a while. She is at the other end of the bar, or the bathroom, or maybe out back somewhere, and in her absence women start applying themselves to Saranova. One attaches to his hand like a limpet. Others try very hard to make casual eye contact. Jordana, a mesomorphic brunette, rues her fate of being a woman and swears to him that her fondest wish is to become a man.

"If you do," Saranova says, "underwires everywhere will despair."

9:45 p.m. Such is the vying for Saranova's attention that I need to take a break and so I step outside, but that does little to improve the situation, as I see coming toward me at full steam one of Saranova's exes. Actually, I'm not sure he ever dated her long enough for her even to be ratified officially as an ex, and as I don't want to stick around to debate the finer points of her taxonomy, I duck into Café Palm—another of my favorite hangouts that, tragically, closed just a few weeks after this night.

And lo, standing in a spotlight, clutching a microphone, and belting out some Jefferson Airplane, is another one of Saranova's former inamoratas. I knew this woman was a singer, and that she often performs at the Ritz, but I had never heard her perform before, and for a moment, as I stand there listening to her, everything just . . . disappears. Her voice is that good. It's not easy to do justice to the vocal power of Grace Slick, but this tiny woman nails it. She can't be more than five feet tall, and the idea of that body producing such a pure, thunderous, gut-clearing sound is almost incomprehensible. It is also mesmerizing. No one talks, no one drinks, no one fidgets. For the entire duration of the song she notebinds the room.

When it's over and the crowd recovers from its paralysis, I find myself chatting with one of Café Palm's servers. She is beautiful, and charming, and has an irresistible Québécois accent that makes you want to keep asking questions just so you can have the pleasure of hearing her answers. But I realize that all my questions make me sound like an undercover cop, and then it dawns on me, even more uncomfortably, that statistically the chances that this woman is in some degree of love with Saranova are pretty good, and so I mumble something valedictory and limp away, disheartened and feeling generally the same way I did when I tried and failed to ask Alexis Ploof to the prom. ("What is that?" sneered the Ploofer. "A corsage?" "No way," I lied. "It's a cupcake. See?" Then I ate it. And ran.)

I resolve never to tell Saranova about this story.

Correction: either story.

10 p.m. Back in Selva, Saranova is now Betsyless and operating without restraint. He seems relaxed now, relieved. A certain number of women constellate around him while a collection of aspirants poke their heads through the crowd in such fervent hope of getting some attention that it looks like some kind of undignified game of Whack-A-Mole.

Things are accelerating.

11 p.m. Jordana is there now, too, and she has a friend. The two of them act pouty and kittenish and spend so much time rubbing against each other, challenging and invitational, that it's amazing they don't zap each other to death with static electricity. The show is mainly for Saranova, naturally, but it makes me uncomfortable enough that I relocate temporarily to another end of the bar where I end up having a perfectly civil conversation with two well-dressed women who have just come from the symphony or similar.

At first it is refreshing. At first it is normal. At first it is just decorous barroom chitchat.

But then it comes out that one of them, a lithe and elegant ballet dancer, is—you guessed it—one of Saranova's exes and, as it will come out later, not one with whom he has remained on very good terms. I can't help but marvel at how he handles all this. I mean, there have been three exes in the last hour and all within 50 feet of each other. Treading the downtown territories for him—and therefore for me—requires negotiating a minefield of exes and applicants and grudge-nursers that is so treacherous and so dense that it would confound even Pol Pot.

Yet there he is, our Saranova, swanning about the bar, joking, laughing, flattering, cajoling, flirting. And although I can perceive some sensations of ill will lasering around the room, he is totally unruffled. In fact, when we leave Selva for another bar, our group includes both Jordana and the ballerina. And although I feel like it is courting slappy doom and hurled beverages to construct a group like this, I marvel at Saranova's appetite, and his unflappable diplomacy, and his wily coolness.

He is downright Clintonian.

Midnight. We relocate to the Jolly Bar, which is playing the kind of music you'd expect in an Eastern Bloc nightclub five years ago. That's what this scene is about: pounding unfamiliar rhythms, hors d'oeuvres that are juiceless and wan, incomprehensible scenes playing out at other tables. And trying to get a drink as a single man and an out-of-towner whose tipping habits are unknown is like waiting on the list for an organ transplant. After a dispiriting quantity of time trying and failing to gain service, or even attention, I tell Saranova that we should relocate. He agrees. And he says we should shed the women because we're going to someplace called Cheetah's.

12:30 A.m. We are chauffeured in an executive sedan to the strip club, where we are hailed by bouncers and hastened through the crowd, past the ropes, and into a sparsely populated VIP area. I never know where to look when I'm in a strip club—even though out of all the places on earth, a strip club is probably the one place where that decision should be easiest to make—and so I am amazed when a fingernail traces a prickly line from my neck down my arm. Next thing you know I am getting a lap dance. Saranova has sent over a girl as if he were sending over a drink (which he does also) and we sit there, in our adjacent chairs like pilot and co-pilot, getting our twin lap dances. I spy on Saranova, who is perfectly comfortable and receives the attention gracefully and with the aplomb and easy entitlement of a long-reigning monarch.

I am less suave with mine.

"Hey, sugar," I am told, "you don't have to handcuff yourself."

I realize that I am leaning backwards away from my dancer with my hands clasped tightly behind the chair. I don't tell her that I'm recoiling not just because I am unsure what sort of protocol obtains in Floridian strip clubs but because I am not naturally enticed by women I've never met before giving me colonoscopically detailed views of their most private recesses. I also don't tell her that I have historically avoided strip clubs because I always find it depressing when I realize that I now have something in common with those guys over there. Guys who I would normally go to quite a bit of trouble to avoid.

But, to be fair, Cheetah's isn't as bad as I expected it to be. The bouncers don't look as if they are considering doing something painful and embarrassing to you and the women are all healthy and clean—some are even so attractive I can imagine them on a different kind of runway—and if they aren't exactly in paroxysms of joy to be rubbing themselves on all the welfare drinkers and dip-chewers and awed-looking retirees and tattoo enthusiasts, the dancers don't seem to be in distress, either. And they aren't begrudging or streety or joyless or mean. In fact, their dancing isn't even precisely erotic; it is, more than anything, simply athletic. The whole spectacle is like attending a gymnastics meet that also happens to feature alcohol and nudity.

They pay particularly close attention to Saranova, naturally, and as I observe him through naked poses that are like X-rated versions of that famous leggy viewfinder shot in The Graduate, I can't help wondering how Saranova reconciles this kind of thing with his affection for Betsy, which I can tell is real.

I notice also that even though I have now been informed by an authoritative source that it is O.K. to "do some light touching with the girls" that Saranova's hands are clasped firmly around his drink. He hasn't given his dancer even one neighborly frisk.

It additionally occurs to me that throughout the night, despite the women who have applied themselves to Saranova, he has not done anything transgressive. He has received a phone number on a bev nap—embellished, I'm afraid, with the scrolly cursive filigree that one would expect to see in the back of a high school yearbook—but I saw him dispose of it minutes later, in private, without hurting the girl's feelings. He's been attentive with women and has made physical contact with them, but only in chummy zones: the shoulder, the elbow, the forearm. Dimly, I wonder if this is Betsy's influence.

I also wonder if his story tonight isn't so much about his indulgences or his vespertine stratagems or secret roué techniques as it is about—gasp—his reformation.

1:35 A.m. As we leave—and, I think, mainly by virtue of being Saranova's sidekick—a stripper gives me a prim and crisp kiss on the cheek. Then we push out of the bar, past the last-minute smokers and vigilant bouncers and swaggering fortysomething men in twentysomething clothing sporting heavily begelled Gotti-style haircuts, and into the Lincoln Town Car waiting for us. This driver is the same guy who once flew to Dallas to pick up a Suburban belonging to one of Saranova's girls just so he could drive it back to town for her. He gives the impression that his devotion to Saranova includes things like breaking kneecaps and/or taking a bullet, but for now he just speeds us back downtown.

1:45 A.m. I have been remiss. I haven't yet mentioned Saranova's Scotch glass.

Everywhere he goes, Saranova has a tumbler filled with single malt. It's a constant, cut-crystal accessory and he keeps it always within arm's length, like a gunslinger's pistol. And none of the bars seem to mind when he shows up with it, or when he leaves with it. It is just another aspect of his privilege.

1:55 A.m. We encounter some trouble at The Gator Club. The bouncer must be new, because he eyes Saranova's glass disapprovingly and prohibits us, chestily, from entering. It's already been last call, apparently, and the guy's being firm about it. This is the first time I have ever seen a door fail to open for Saranova. He is supremely displeased, I can tell, and he makes a few overtures that verge on real hostility, but somehow I talk him down.

That's the good news. The bad news is now he wants to go to the Ivory Lounge.

2 A.m. I hate nightclubs. I always have. They offer such a dumb spectacle, and are always rife with falsity and bravado and faux-sexiness and screechy histrionics. And there is always some other place to be, or to see and be seen; this is particularly a problem at Ivory, which has two main rooms, and so you go from one room to the other and back again. It's like playing some kind of torturous, life-sized game of Pong that also happens to feature deafening and annoying music.

At 10 o'clock the Ivory Lounge was so empty that it seemed doomed, but by now, at 2 a.m., it has been resuscitated by hooligans and posers and women who are on the wrong side of gravity; everywhere you look you see them, in tube tops and heavily whiskered jeans and bad-idea heels, leaning on cars for support or falling into bushes or dashing someone's cell phone into shards on the concrete. And there are trolling taxicabs and irritable bouncers repossessing glasses from people's hands and everything smells like off-brand cigarettes and Axe Body Spray and the albumin stench of late-night striving. All the men with gym muscles in too-small shirts who have invested time and shot-money into just-met women are trying to close with the hard sell, and there is so much touch-and-rebuff that it looks like a drunken judo tournament.

There isn't much time to dwell on the scene, though, because a guy is trying to pick a fight with Saranova. I don't like this guy's odds—he is so drunk that his face looks like a blancmange and he is so unsteady that it's hard to tell if he is trying to lock in the telemetry to launch a haymaker or to nuzzle up to Saranova's shoulder for a cuddly nap—but given that the accusation he is leveling so lispily at Saranova seems to involve a matter of high honor, I have to give him a puncher's chance.

"I don't know," Saranova says pleasantly, "I guess it's possible that I slept with your girlfriend."

Through some stick-'em-up hand gestures and a few incomprehensible words, the guy indicates that he'd like to redress this grievance manually. I pull on Saranova's arm and ply him with a few schoolyard clichés about pacifism—he isn't worth it, you don't have anything to prove, blah blah blah—but Saranova, a guy I had hitherto given no credit in the fisticuffs department, is solid as a rock. His body is unclenched and seemingly relaxed, but I can tell that his reflexes are on full alert, and I realize that the odds of this article's final chapter ending up in a holding cell—or an emergency room—are suddenly very great.

Again I pull on Saranova. Again he doesn't budge.

"If you want to fight about it," Saranova says companionably, "we can."

The guy makes another frothy, nearly incomprehensible accusation.

"Like I said, buddy, I don't know if she slept with me. Maybe she did. And who could blame her? Look at yourself."

Miraculously, the guy does just that. He literally looks at himself as if contemplating a mathematical formula he will never understand, and then, somehow, the situation resolves nonviolently, mainly, I think, because the guy couldn't think of anything else to say. He just kind of teeters away, defeated, and Saranova shrugs. Just another night out on the town.

Until this minute I had considered going out with Saranova as simply an endurance event, a kind of biathlon of drinking and flirting, but now I realize that given the sort of lifestyle he leads, and his serial success with women, that his nights sometimes involve a third and final event:

Fighting.

And I can tell from just the last few punchless minutes that Saranova knows very well how to handle himself. That is a big surprise to me—but not as surprising as what happens next.

2:15 A.m. Somehow I am able to convince Saranova that it's time for me to go home. I walk him to his apartment, and then, as we say good-bye, I get the shocker.

"Know what?" he says, his face flushing with embarrassment. "I'm really relieved to be home. I'm looking forward to just going to sleep with Betsy. Tonight I kind of . . . you know . . . missed her."

Then he experiences a sudden jolt, as if he's had an epiphany, or gargled several nine-volt batteries. "But hey, listen, I have an image to uphold in this town. I mean it. Seriously: Don't put that in your article."

"Don't worry," I say. "I won't."

Novelist Adam Davies is the author of The Frog King, Goodbye Lemon and Mine All Mine. He has been a writer-in-residence at New College of Florida, and in August won an award for "Best Feature" from the Florida Magazine Association for "The Kate I Knew," in our summer 2011 issue. And yes, he assures us, Saranova is a real-life person.

Click here to read an interview with Adam Davies about the writing and research of this piece.