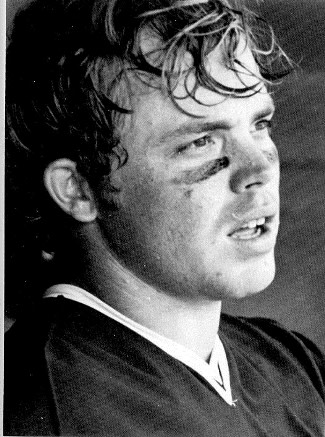

Baseball Hero

By Dan Connolly

It took some time—into the middle of his sixth decade, in fact—before Buck Showalter could be content being Buck Showalter.

Sports pundits and baseball fans have criticized him as an unyielding perfectionist and taskmaster. They’ve said he’s too intense, and that his constant motor and exacting eye for detail eventually wear out his welcome wherever he is employed.

Showalter, manager of the Baltimore Orioles—who have hosted spring training at Ed Smith Stadium in Sarasota since 2010—says he has simply stopped paying attention to how he is perceived. There was no watershed moment or epiphany. It’s just that he’s 56 now, he says, older, wiser and “comfortable in my own skin.”

But if you want to get under that skin, if you want to see his cheeks redden and his jawbone clamp, suggest that he is the primary reason that the moribund Orioles, after 14 consecutive losing seasons, finally made the playoffs in 2012.

Put his picture on all Orioles’ propaganda, give him his own billboard and attach a Showalter-centric slogan—“Buckle Up”—to the club’s improbable pennant run. Tell him that he is the face of these resurgent Orioles. Then step back and watch him wince. Watch him cock his head to the right, furrow his brow and deliver one of his favorite phrases in his slight Southern drawl: “You had to go there?”

He gets more passionate as he continues. “It’s not about me. I really mean that. That’s what makes me uncomfortable,” says Showalter, who has finally found a home in Baltimore after managing, and being fired by, the New York Yankees, Arizona Diamondbacks and Texas Rangers. In January, management offered and he agreed to a five-year extension of his contract. “There’s no Joe Hero here, or this is the guy who should get all the credit. I am serious about being just one of the parts,” he insists.

It’s true that Showalter never threw a pitch in 2012. He never homered or stole a base. But his steady demeanor and expert, continuous button-pushing cannot be overlooked.

“Our team wouldn’t have been anywhere close to where we were at the end of the year if Buck wasn’t the man in charge of it all,” says Orioles All-Star catcher Matt Wieters. “He was the man for the job and the best manager for us, for where we were [in 2012] and where we are going to be in the future.”

The Orioles weren’t supposed to be anywhere but in the basement of the American League East again in 2012. But from the beginning of spring training, when Showalter bused his players to a Sarasota movie theater to view an inspirational video that included movie clips, 2011 Orioles highlights and a message from Baltimore Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis, Showalter preached the gospel of victory through unity.

By constantly talking about “sum of the parts,” and using more than 50 players throughout the season, many of them excelling in limited roles, Showalter made sure the Orioles were team-first. That mentality kept the club in the playoff race when everyone expected them to fade in August and September, and helped them push the well-heeled Yankees to an elimination game before losing in the AL Division Series.

The tremendous turnaround earned Showalter finalist status for Manager of the Year and the hearts of Orioles’ fans—although he deflected all the praise and continued to charge full speed ahead, working day and night, seven days

a week.

“I know Buck doesn’t have an off button,” says former Orioles president Andy MacPhail, who hired Showalter in 2010. “But in getting to work with him, you learn he doesn’t have a pause button,” either.

To best understand William Nathaniel “Buck” Showalter III, to know what really makes him click, you have to go back to Century, a small town in the Florida Panhandle, just a couple miles from the Alabama border. Showalter has had managerial jobs in some of the biggest cities in this country. He is a multimillionaire and top performer in a highly public profession. But he is still—and always will be—small-town Florida.

“I grew up in a nice area. Everyone had a relationship with everyone,” he says. “You had to have a relationship with everybody. I mean, we had two churches and you went to one or the other.”

His mother was head of nursing at a small 30-bed hospital—“you’d probably call it a first-aid center nowadays,” he says—and his dad, Bill, was a former small college football star in Tennessee who had become a high school principal known for his steadfast principles. When the teachers at Century High School walked out as part of the 1968 Florida teachers’ strike, Bill Showalter walked out with them, even though the school administration warned him he’d never again work in their district. He believed showing solidarity was the right thing to do.

“He always said you have to plant your feet down if there is something you believe in,” Showalter says of his father. “Even if it meant he’d never work as a principal again. Two months later [district officials] were back in front of him on bended knee.”

Bill Showalter was tapped to oversee the integration of newly created Carver Middle School, Century’s former all-black high school. One of his first acts was to take his wife, three daughters and son to the area’s African-American church on a Sunday morning.

“You should have seen the looks we got,” Showalter says. Decades have passed, but Buck Showalter believes he relates to a wide spectrum of players in a now international game because of what his father instilled in him as a boy.

“He wasn’t doing what was popular. He did what was right,” Showalter says. “My dad was so far ahead of his time with his relationship with the black community and the lessons he taught us.”

It didn’t stop with race relations. The father taught the son not to complain, and, instead, fix what wasn’t fair. A three-sport athlete at a high school so small that it couldn’t have a marching band because all the boys were needed to play sports, Buck Showalter remembers a varsity baseball game in which he hit a ball to right-center that should have been extra bases, if not a home run. The high school field, however, had no outfield fence and was bordered by a large pecan tree. Showalter’s fly ball struck the tree and bounced back to the infield, holding him to an unfortunate single. It was a tough break, and one that infuriated the young ballplayer.

That summer, father and son worked together for about two months to put a fence around the field, cut down that tree and burn out its remnants. No complaints, son. Just improve the situation.

“Have you ever tried to get a stump out of [the ground]? Whoa,” Showalter chuckles at the memory. “Now that I look back on it, it was bonding. We’d work and talk about life.”

Perhaps the most crucial lesson passed on from father to son was the importance of humility. Always put substance over style. Don’t crow about your accomplishments. When Showalter scored high school touchdowns, end zone celebrations were not accepted.

His father would drive a couple hours to see his son play baseball at Chipola Junior College, but he’d never make his presence known. He’d just sit in his truck, watch the game and then go home. There were plenty of times that Buck didn’t even know his dad was there until after he left.

It wasn’t until after his death that Buck learned his father had won a Bronze Star for meritorious service in World War II. Discovering that medal in the collection of his father’s things delivered a profound message: Concentrate on actions, not words or lofty awards.

“I try not to have an agenda. It sounds corny, but I just want to impact people’s lives,” says Showalter.

As a young man, he dreamed he would make that impact as a baseball player. A 5-foot-9, left-handed swinging first baseman who went on from junior college to win first-team All-America honors at Mississippi State University, Showalter was drafted in the fifth round by the incomparable Yankees in 1977. He spent seven years in the minors, never receiving a big league promotion, partially because his path at first base was blocked by perennial All-Star Don Mattingly.

Although he was nearly a career .300 minor league hitter, Showalter’s best baseball tool was his brain. He came to the park early, left late and asked so many questions that his teammates and coaches knew that he’d be managing at some point. That didn’t take long.

In 1985, he was 29 and managing the Yankees’ Single-A affiliate in Oneonta, N.Y. By 1990, he had been promoted to the Yankees’ coaching staff and, in December 1991, at the tender age of 35, he’d ascended to manager of the planet’s most famous sports team.

A few weeks later, Bill Showalter died. Shortly thereafter, William Nathaniel Showalter IV, Buck’s second child and only son, was born. It was the ultimate emotional roller coaster—losing a father, gaining a son and realizing a professional dream in a matter of weeks. It set the stage for a career that would have exceptional highs and crushing lows.

Showalter led the Yankees to their first postseason appearance in 14 years when they earned the 1995 American League Wild Card. But he was fired after that season, primarily because he refused to can members of his coaching staff—a decision his late father surely would have supported. His replacement in New York, Joe Torre, led the Yankees to a World Series title the following season, beginning a disturbing trend in Showalter’s career: his immediate successor shepherding Showalter’s former club to a World Series.

Showalter quickly found another job after he left the Yankees, becoming the architect and manager of the expansion Diamondbacks, who he helped build from scratch. He had another strong run, which included a 100-win season in 1999, but he was fired in 2000 when Arizona fell back to third place. The next year, the Diamondbacks won the World Series, beating the Yankees—while Showalter watched as an ESPN analyst.

He got another shot to manage in 2003, taking over a last-place Rangers team and again producing a turnaround that earned him his second manager of the year award in 2004. Yet he was fired after the 2006 season, when the Rangers decided to clean house and rebuild. The man who replaced him, Ron Washington, took the Rangers to consecutive World Series in 2010 and 2011.

Three times Showalter helped infuse winning into a ballclub only to see it reach the pinnacle of the sport after he was dismissed.

“It’s kind of like raising your daughter and then letting someone else walk them down the aisle,” Showalter said during his introductory press conference as the Orioles manager. “I hope to get to walk them down the aisle here.”

When Showalter took over the Orioles on Aug. 2, 2010, the club was about as far away from baseball’s altar as possible. They were on pace for the most losses for a season in club history, and attendance had dipped to the lowest point in the two-decade existence of Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Although Baltimore had been a baseball town, fans now were switching their attention to the NFL Ravens by early August, leaving the Orioles to listlessly play out the season.

The Orioles didn’t just need a turnaround; they needed a miracle worker. What they got was an old-school tactician with an authoritative presence and a penchant for subtle adjustments.

In his first week on the job, Showalter approached former Orioles infielder Robert Andino, a Miami native who often wore his ballcap cocked sideways, hip-hop style. Showalter said it was unfortunate Andino’s hat was the wrong size and escorted him to the equipment manager’s office for a better-fitting lid. Nothing more was said, but Andino got the message—the bill of his cap pointed forward during games after that.

Showalter did a lot of tweaking in his first year at the helm, making changes that had less to do with performance and more to do with attitude, consistency and accountability. He demanded professionalism from his players and, in turn, did his part, constantly studying opponents, continually looking for an edge.

“It’s always been his preparation,” says Wieters, when asked what makes Showalter so effective. “It doesn’t matter how late the game might have gone the night before or how much time he’s had to get the information. Buck and his coaching staff give us as much information as any player needs to put together a game plan and be ready to go for a series.”

The results were immediate. The Orioles won 34 of their final 57 games in 2010, the second- best record in the American League from when Showalter took over until the end of the season. They struggled in 2011, but made enormous strides last year, winning an incredible 24 more games than in the previous season. They captured a one-game Wild Card playoff against the Rangers before losing to the mighty Yankees in five games in the American League Division Series.

Baseball’s writers took notice, voting Showalter runner-up for AL Manager of the Year, just behind Oakland’s Bob Melvin, whose low-budget A’s won the AL West in 2012. Those in the game have been well aware of Showalter’s adept managing skills—from picking the right reliever for the right situation to getting 25 different personalities to play as a team—for years.

“The way I evaluate [opposing] managers is, ‘Am I worried about what he is going to do?’” Melvin says. “Am I worried about what he is doing? Is some of my focus always taken off what I am doing to make sure I know what he is doing? And Buck has always been one of those guys.”

For example, he flew into Sarasota in January to make sure that all the practice mounds at Ed Smith Stadium were graded at the same level. Last year, he explained, the lack of uniformity in the mounds caused some of his pitchers to perform inconsistently.

He’s proud of the myriad changes to the organization that most people don’t notice but that have helped raise the Orioles’ game. One big change was the switch in spring training complexes from dilapidated Fort Lauderdale Stadium in South Florida to the newly renovated and state-of-the-art Ed Smith facility in Sarasota.

“It’s a place everybody looks forward to going to,” Showalter says. “[The Ed Smith complex] just fits into that community. It’s nothing garish. It’s baseball. And it has just eliminated another excuse. That’s one of the things that I wanted to do here. Limit the excuses that we’ve been using for failure.”

It’s that accountability he has championed since he arrived in Baltimore. It’s that culture of losing that he’s been chipping away at, like a tree stump on the edge of his hometown field. He does it like that small-town boy from Northwest Florida, who, all these years later, is still pursuing his childhood dreams by succeeding in a kids’ game.

“I have a blast every day. I enjoy what I do. I enjoy being around the players. They make me laugh. They make me stop taking myself so seriously,” Showalter says. “There’s not a day goes by that I don’t think, ‘God, how lucky am I?’”

Web Extra: Spring Look

The Orioles' 2012 playoff run defied all odds. Can Buck Showalter take Manny Machado, Adam Jones and the rest of the young O's back to the postseason? CBSSports.com's Danny Knobler looks ahead to the Orioles' 2013 season.

Baltimore native Dan Connolly is in his 13th season covering the Baltimore Orioles and Major League Baseball, the last nine of which have been for The Baltimore Sun. He is the chairman of the Baltimore-Washington chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.