Inside Feld Entertainment's Center for Elephant Conservation

It's a September morning near Polk City in rural Florida, and entertainment mogul Ken Feld is feeding apples to his Asian elephants. Two of the elephants, Emma and Shirley, are massive, commanding attention just as they do when they perform in the ring as iconic stars of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. The little one in the middle, two-year-old Piper, is probing Feld's hands with the tip of her serpentine trunk. For all their size, the elephants are behaving like excited pet dogs. It could just be the apples, but for Feld, these animals are dear. Piper, after all, is named for Feld's own granddaughter.

"You can go to any Ringling Bros. Circus, the first time the elephants come out, there is an audible gasp and cheer," Feld says. "It's a sight, it's a feeling and it ultimately gives you an emotional connection. There's nothing else like it."

It's ironic, I think, as I watch Feld with his animals, that we so often equate physical strength with power. Though they are the definition of strength, the half dozen elephants I'll be introduced to today—some surpassing 10,000 pounds—allow their behavior to be controlled by vastly smaller humans. As he leads me around his elephants, some of them retired animals from his circus, where they can perform into their 50s, Feld makes me think of a maharaja visiting his menagerie. Asian elephants, after all, are documented to have been tamed on the Indian subcontinent for at least 4,000 years, used in labor and war and kept by kings as expensive pets, symbols of wealth and majesty. If there's a contemporary equivalent of that kind of power, Feld is certainly it. The physically modest man is master of an entertainment empire with annual revenues estimated at $1 billion.

Since taking the reins of Feld Entertainment on his father Irvin's death in 1984, Ken Feld, 65, has grown the company into, as its website proclaims, "the largest producer of family entertainment in the world." Thirty million people in 74 countries attend his Ringling Bros. Circus, Disney on Ice, the monster truck extravaganza Monster Jam and other live productions. Siegfried & Roy was Feld's, and next year, Feld will partner with Marvel and its comic book heroes to stage Marvel Universe Live.

The billion-dollar company is in the process of transferring its world headquarters from Virginia to an expansive complex in Ellenton; Feld has been a Tampa resident since 2006, is on Sarasota's Ringling Museum of Art board, and is renovating a property for himself and his wife, Bonnie, on Lido Key. Today he's at his Ringling Bros.' Center for Elephant Conservation (CEC), a sprawling, 200-acre ranch with a staff of nearly 20 just outside Polk City, home to 29 pachyderms, ranging in age from two months to 67 years. Another 18 elephants in his herd—the largest in the Western Hemisphere—are currently on tour with the circus.

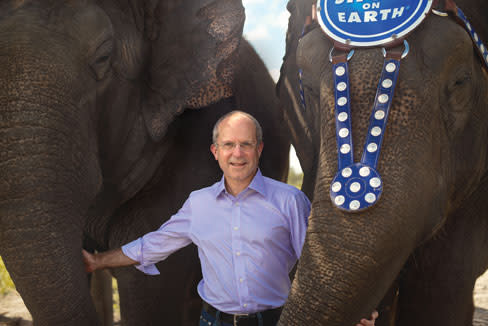

Feld is neatly dressed in a purple button-down shirt and blue jeans, his graying hair as closely clipped as topiary. He has the air of Kevin Spacey in the D.C. political thriller House of Cards, a pool of quiet power, the boss in the room. As he pets Piper's trunk, he describes the plight of the Asian elephant, an endangered species the World Wildlife Fund estimates to have a remaining wild population of roughly 30,000 (another 16,000 in captivity); the 1975 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which made it nearly impossible to import the animals; and his CEC, whose motto is Research, Reproduction and Retirement.

"Those are our three pillars," he says. "With CITES, I knew if we didn't do something, there could be a shortage of Asian elephants in the U.S. and kids wouldn't have a chance to see these incredible creatures. We started the program in the early '90s at a much smaller facility in Williston, Fla., based on our elephant people and veterinary staff, a combined hundreds of years of experience. We love these animals, have a commitment to their lifetime care. Our caregivers spend more time with them than we do with our kids."

As Feld leads a tour of the CEC's big, grassy paddocks and sturdy fences, it's clear that he has spent money here. Aside from the cost of the land, he estimates he's invested $8 million. The annual expense of feeding and caring for each elephant, he says, is about $65,000.

Circus animals have increasingly become a divisive issue; many countries have banned their use, and Rep. Jim Moran (D-VA) proposed a U.S. ban on traveling exotic animals in 2011, supported by celebrity activist Bob Barker. Critics argue that because of CITES, Feld's motivation with the CEC is to maintain a reliable supply of animals for his circus. Asian elephants hadn't been imported into the U.S. in more than 30 years, until earlier this summer when the Denver Zoo acquired one from the Antwerp Zoo.

"Clearly, [breeding elephants] was part of the motivation," says Feld. "But the center has turned out to be so much more. The research, what we are doing out in the world, this could be what lives on longer than anything else [of Feld Entertainment]."

Along with operating a training program in elephant care (it recently attracted 100 applicants for six open slots, a ratio, Feld jokes, that's "better than Harvard"), the CEC regularly hosts researchers, recently footing the bill for a group from countries including Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Indonesia. The CEC's research and conservation scientist, Dr. Wendy Kiso, is an expert in sperm cryopreservation and has established a genome resource bank in a set of liquid nitrogen tanks housed here. To date, the CEC has seen 26 live births, only one from artificial insemination. Kiso is working to improve that rate; many of the breeding-age females are star performers who travel with the circus, and to bring them back to the CEC for breeding disrupts the herd.

The CEC has had particular success in managing the elephant endotheliotropic herpes virus (EEHV), a disease that quickly kills 80 percent of the elephants it infects. Barack, one of the few known Asian elephants to have survived the disease, lives at the center. Feld has given more than $300,000 to the Smithsonian's National Zoo for EEHV research. He also supports collaring, survey programs and elephant orphanages in Asia.

Next Feld takes me through a long and cavernous elephant house that recalls the ancient myth of the stables of King Augeus, which were so vast that Hercules had to divert two rivers to clean them out. I see solitary male elephants inside sturdy steel pens that have rods nearly as thick as telephone poles with spaces in between: trainer's emergency escapes. Performing elephants are nearly always Asian elephants—smaller and more manageable than their African counterparts—and female. Bull elephants are loners and regularly enter a testosterone-charged state called musth, which causes them to attack trainers and other elephants alike. But handlers know that every elephant can be dangerous.

At the CEC, each male gets its own house and acre of land; all the elephants are fed a diet of specialized hay, and are groomed and exercised daily. Zoologists such as Jack Hanna, director emeritus of the Columbus Zoo, have given the CEC their endorsements. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health and Inspection Service is responsible for its regulation.

On a covered deck with elephants grazing in the distance—they look like big, isolated gray boulders on the flat ranchland—Feld talks about Shakespeare, saying that every story currently told originated with the Bard. I quip that Feld is like King Lear, because of the ongoing succession of his company to his three daughters, Nicole, 35, Alana, 33, and Juliette, 30.

Then the conversation returns to elephants. Those who point out Cirque du Soleil's success without using animals are not making a fair comparison, Feld says. "Soleil is a different style, a different audience, and it's pricier," he explains. "We're about families. They get to see Asian elephants, and they get to see them live. Ultimately, they get a connection. [The elephants] are ambassadors of their species."

In 2009, Feld won a long-running, major case brought by animal rights groups including the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals that accused Ringling Bros. of abusing its elephants. Among the claims were that Ringling handlers beat the animals with ankuses—short-handled, hooked goads used since antiquity in elephant husbandry—to get them to perform, regularly chained them for many hours, ignored sick elephants, and caused unnecessary elephant deaths.

The case garnered major media attention and was decided by U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan, a Clinton-era appointee and environmental thorn in the side of the Bush Administration.

In ruling in Feld's favor, Sullivan cited payments the animal rights group made to their star witness, former Ringling Bros. employee Tom Rider, and wrote, "Rider was essentially a paid plaintiff…whose sole source of income throughout the litigation was provided by the animal advocacy organizations."

For Feld, the case was a wrenching, bitter experience, and he still savors his victory. "It has been since 2000, 13 years of my life," Feld says. "What hurt me most were the attacks on our people who spend their lives with these animals. Winning was the biggest vindication that we've ever had. As part of that, we were granted the right to get attorneys' fees." Feld has asked for $25.4 million in attorneys' fees from the three animal rights groups involved. "The ASPCA came to us in December of last year; they settled for $9.3 million. You're contributing to the ASPCA and $9.3 million of your money is coming to us? That's a huge problem they have now."

Sullivan also allowed Feld, who spent $22 million defending the case, to countersue ASPCA and its co-plaintiffs for additional damages under the federal Racketeer Influenced & Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). That case is scheduled for 2015. Highlighting the strength of the countersuit, the online journal Animal People reported in March that out of seven previous "major Endangered Species Act cases since 2002," Sullivan ruled in favor of animal rights groups in all of them.

Feld has not been without his defeats; he settled out of court with another animal rights group in 2001, and in 2011 paid a $270,000 fine for violations of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), the largest AWA fine ever handed out by the USDA.

Yet he has largely been silent to the media about his views on his animals and animal-rights activists. But today, as we look out at his herd, Feld outlines his stance on the issue. "The animal rights groups have blurred the line between animal rights and animal welfare. Our company is the No. 1 practitioner of animal welfare in the world, but we are not a believer in animal rights," he says. "It's not to diminish the intelligence of these creatures, but you can't equate them to human beings. The animals that are inclined to perform and want that kind of training and discipline, it gives them a kind of purpose. If you want to put a human emotion on it, people that get up in the morning and have some place to go, something to do, that accomplish something, they're probably healthier and at a better mental state. They have everything they need. Their enrichment is to perform."

Many animal-rights activists might take furious issue with those statements. But it's clear that Feld is utterly convinced of what he's saying, and that his affection for his elephants is real.

It's time for pictures, and Feld enters a grassy paddock. Two trainers lead their elephants, Alana and Icky, forward and dress them with the familiar The Greatest Show On Earth headpieces. The trainers are carrying ankuses, and they gently tap the animals' sides and trunks with them as they issue stern voice commands: "Icky, back. Alana, steady."

What does she like about working with elephants, I ask Icky's trainer, Laura Keith. She glances up at her towering charge. "I love that somebody my size can stand beside a 10,600-pound elephant," she says.

As the photographer wrestles with a reflective umbrella, Ken Feld gets in position, a small man between two huge elephants, murmuring to them in a low, tender voice. The photographer is having issues, the elephants begin to sway and Feld finally snaps, "It's not like we're shooting statues here!"

Feld has made his point. The picture gets shot.

"Whatever someone's thoughts were coming through the door," Feld says, "they've left here thinking, 'This is a place that does a lot of good.' There's too much in it from human resources, to financial resources, to the caring, to the vets. We don't look at these animals as property. We look at them as family. This is part of my legacy, absolutely."

A CEC official on the power and personalities of her charges.

In 1972, college student Janice Aria enrolled in Ringling Bros.' Clown College, figuring it would help her keep students engaged when she became a teacher. "The first week they put me on an elephant," she says. "It was kismet."

Today, after a circus career that included owning performing bear and dog acts, Aria has returned to her love affair with elephants. As director of animal stewardship at the Center for Elephant Conservation (CEC), she oversees the center's program for circus elephant handlers, an intensive and strenuous introduction into the behavior and psyche of the earth's largest land animals. Elephants, says Aria, are "hugely intelligent; they're hyper-vigilant and notice everything."

Even babies quickly learn to understand the word "no" or to pick up their feet for grooming, and older elephants are smart enough to indulge in forbidden behaviors, like shoving an enemy, the second a trainer turns his back. They have a "beautiful social structure," she says, with a well-established pecking order, deep bonds—and sometimes deep antipathies, too. "Their personalities are so individual," she says. "Some are sociable, some are mean, and some are kindly and cooperative."

Only about a third of the elephants they work with are suited to become performers, says Aria. "You can see pretty quickly which ones have the focus, the ability to thrive in a highly stimulating environment and the disposition to travel." But some love performing so much they'll pine away after being retired. The CEC has even transferred a few elephants like that back to the circus. "You'll see them standing on the side of the act," she says, too old and creaky to keep up with the performance, but content to be part of the familiar routine.

At the center, elephants spend their days outside, but walk back, linked trunk to tail, to the barns at night. They're hand-scrubbed every day, and will run across a pasture to their trainer when their name is called.

Still, Aria emphasizes, "They're trained, not tame, and they're definitely not gentle giants." That sobering truth is drilled into every handler every day.

The more she's around elephants, Aria says, the more she's awed—by their grandeur, their agility and speed (up to 25 mph), and their "phenomenal" trunks, which are strong enough to knock down trees and dexterous enough to extract a tiny peanut from a shell. "And they're so quiet," she says, designed to pad through the forest without making a sound despite their massive size.

In the old days, says Aria, most circus elephants were made to perform, and they were taught tricks, like standing on one foot, that weren't natural behavior. Today everything you'll see at the circus, like elephants standing with their front feet on another elephant, builds on natural behavior.

"We've come a long way," she says, and although she says many animal rights activists are misinformed, she's quick to credit their scrutiny for improving the treatment and training of circus elephants.—Pam Daniel

Novelist and part-time Sarasota resident Tony D'Souza interviewed Nik Wallenda for our June 2012 issue. He's won a number of awards for stories he's written for this magazine, including a first-place for Best In-Depth Reporting and a second and third place for Best Feature Story from the Florida Magazine Association and a third place Green Eyeshade Award for Best Investigative Reporting.