How to Score at Sarasota's Best Mid-Century Modern Auctions

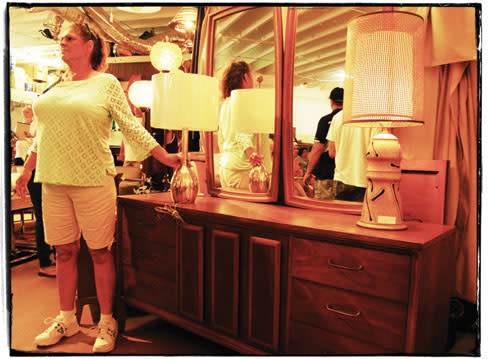

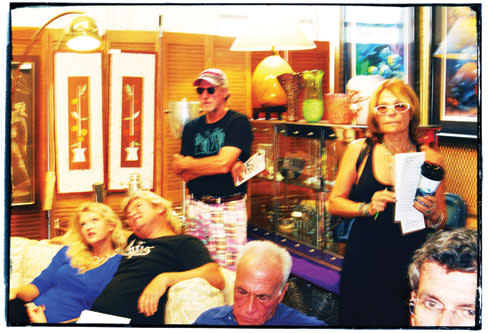

It's Sunday at one of Elliot Bernstein's bimonthly auctions, and around 11:30 a.m., the crowd starts to gather to look over the goods. Many have been to the preview the day before as well, and thus have had time to do a little research on eBay, 1st Dibs, and other online sites. People make notes on the five-page catalog, circling the things they're planning to bid on and scribbling a dollar amount for how high they're willing to go. There's a pleasant, anticipatory buzz, similar to what you might hear from an audience at Asolo Rep waiting for the curtain to go up on a play that's supposed to be terrific.

Over by his cubicle of an office, Bernstein surveys the crowd. He is friends with many of the people here, and recognizes others as regular customers. Today the mix is about the same as always. He estimates that 60 percent are dealers from the surrounding area—defined as anything within a two-hour drive—and they are there to load up on inventory.

I recognize several people from previous auctions. There's Bernabe Somoza, who may well be Elliot's biggest customer. Bernabe runs a company called Mission Avenue Studio, which reconditions—new upholstery, new finish, new paint—good-quality used furniture and sells it both via One Kings Lane, an Internet site with scores of similar dealers, and also at his warehouse/showroom on Sarasota's Manhattan Avenue. I also see Tony McCormack, who is scouting items for his new home in Palm Springs. He has his eye on a trio of paintings depicting a grotesque man reflected in a bathroom mirror. Elliot has hidden them in an obscure corner, feeling they might put off some customers.

The other 40 percent are "retail" customers—collectors, and people furnishing their homes, or just looking for a rug or a lamp. I spot design buff Molly DeMeulenaere buying stuff for the mid-century modern home she's remodeling. I also see some of the town's prominent decorators, people who run resale stores trying to get an idea of what to price things, and people who just like to go to auctions.

At three minutes past 1 p.m., Elliot takes his place behind the podium and welcomes the crowd. He's a tall man in his early 60s, rather distinguished-looking, who just became a grandfather. There are perhaps 200 people present, some sitting in the chairs that have been set out, with the overflow sitting on the furniture to be auctioned or standing around the corners of the room.

Elliot first lays down the rules. Everything is sold "as is." "I don't guarantee anything. If you're smart you will examine it carefully," he says. Chips, dents and other problems are usually not pointed out. From experience I can tell you that this is crucial. There is nothing more disheartening than getting something home and finding a crack. I once bought what looked like an industrial-style end table, to all appearances made of cast iron. When I officially owned it and braced myself to pick it up and take it home, I was astonished to find out it was resin and weighed about five pounds.

As far as provenance and attribution, "You're the expert," Elliot keeps telling the audience, meaning "We're not quite sure what this is or who made it; all we're saying is that it appears to be in the style of, say, Greta Grossman." No estimates are given as to value, except when, very occasionally during the bidding, Elliot will mention that he's seen similar items for sale for X amount, or that the etched glass panel that measures 5 feet by 4 feet and is too heavy for two people to lift, would cost several thousand dollars new. (It went for $100.)

I have several items circled in my catalog. There are three that I'm planning to bid on.

First, a pair of Heywood Wakefield armchairs. Yes, I know that Heywood Wakefield has peaked, but these are particularly nice. They have a 1950s look, but it's a refined one, not at all kitschy. I don't really need them, but I figure that if I can get them for, say, $250, I'll resell them. (Although I should point out that I have a storage room full of stuff I've bought using this line of reasoning, and I've never sold a thing.)

Second, an oddly compelling lamp. Actually two lamps. Elliot's is a great place to buy interesting lamps. These two appear to be very high-quality Italian designs, circa 1960, and are described as in the style of Tommi Parzinger, a famous designer of the period. I have just the place for one of the lamps, and as for the second, well, there's always the storage room.

And third, a dozen doorknobs designed by Ruth Richmond, the well-known Sarasota builder fondly remembered for her great mid-century ranch houses. These doorknobs are Lucite and embedded with what is described as "gold inclusions." They are quite spectacular in a Hollywood Regency kind of way, and for some reason, I want them very badly. Since I can't imagine anybody else would want a box full of old doorknobs, I am hoping to get them for $25, maybe less.

Then, with the crowd's attention firmly focused on him, Elliot announces the first auction lot going up for bids: "A lot of hand painted enamel-on-copper brooches and pendants..."

Today's auction is one of Elliot's famous "mid-century modern" ones that he holds every six weeks or so. There are 323 lots going up for bid, and each one is in some way related to the style that was popular from 1950 to 1980. As you look at it all you can't help but wonder—where does he get all this stuff?

Anybody can make a deal to consign something with him, but the great bulk of his business comes from what he calls "the three D's: Death, Divorce and Downsizing." And since Sarasota has a demographic hold on at least two of these life-altering events, there is a lot to sell. Elliot is hired by attorneys, heirs, and realtors to liquidate estates and leave the premises, as they say in the business, "broom swept." What isn't worth selling gets donated. The good stuff goes to one of Elliot's warehouses, where it awaits its 15 seconds in the spotlight.

Some of the estates he liquidates are quite ordinary. But some are not, and one is always hoping that today there will be items from the Holy Grail of Sarasota used furniture, a Longboat Key penthouse owned by a sophisticated, artistic, often European couple who had it decorated within an inch of its life back in 1965. This means there will be furniture by the masters of the genre: Eames, Paul McCobb, Knoll, etc.

But what sets Elliot's sales apart is his talent as a curator. The mix is always just right. There is furniture, art, jewelry, rugs, ceramics, lamps and chandeliers, plus a healthy dose of wild cards—old toys and athletic equipment, bizarre pieces of folk art, books, vintage patio furniture, a sextant or two.

A New England native and a self-admitted hippie in his youth, Elliot has spent his career buying and selling antiques and used furniture. He's been a picker, an antique dealer, a home remodeler; he's done both flea markets and high-end shows in New York, and he has operated retail antique stores. But when he moved to Florida 10 years ago, he realized there is something about auctions that appeals to him the most. "It's organic," he says. "You clean out houses and sell to the highest bidder. It's a liberal-minded way to recycle the goods. You need a chair? What better way to get it?"

Auctioneers are famous for their lickety-split patter, but not Elliot. He is calm and professorial. He knows his inventory cold, and though he never lectures about it, the audience learns things from his one-sentence descriptions. Sometimes there's a flash of humor. When a lava lamp comes up for bids, Elliot stares at it for a moment and then deadpans, "I think that's the one I had back in my old stash room." Bernabe scores it for $25.

The auction has been under way for an hour or so—it will last more than four hours—when the Heywood Wakefield chairs come up for bids. They are hoisted into the air by the runners, a group of seven or eight men and women who bring each item up when its turn comes and who also spot the audience for bidders. They often serve as a comic foil to Elliot, mugging as they strain to lift something heavy, or striking poses as they display the jewelry. For some reason I'm always reminded of Santa and his elves.

So far, prices have been a little higher than I was expecting. A pair of John Widdicomb hexagonal end tables from the 1970s went for $325. (Rumor has it there's a rich doctor's wife in the audience, and she's got a family room to furnish.) The better pieces of name furniture are doing quite well. A George Nelson chest goes for $210, and a beautiful Paul McCobb writing desk brings $650. Murano glass always does well, and today is no exception. A bird figurine goes for $170, and a bowl for even more. But there are plenty of good, solid bargains. Bernabe gets an ornate crystal chandelier, big enough for a ballroom, for $100, and a cute little desk chair, described as "Charles Eames for Herman Miller" goes for $25. And Tony gets his three paintings for only $45; he was prepared to go to $110.

With the chairs finally on the block, I take a deep breath and focus my concentration. There is an art to bidding, and I can't quite figure out what it is. I've noticed a pattern. Elliot opens at a rather high figure. Nobody bids. He cuts the figure in half. Still nobody bids. Then he cuts to a ridiculously low figure and everybody bids.

Most items are sold after being raised two or three times, but occasionally a bidding war develops. This afternoon's most dramatic involves an Italian lamp designed by Angelo Brotto. It is one of the few pieces in the auction I actively dislike and wouldn't give houseroom to. But the customers have apparently done their research on this one, and the bidding goes up and up until it sells for $950, earning a round of applause. It's the biggest sale of the day.

Elliot introduces the Heywood Wakefield chairs with the dreaded words, "I've gotten a lot of calls on these." I know my hopes are dashed. They are not going to sail under the radar for a pittance, and sure enough, they don't. In fact, they end up going for $675 the pair. Actually, in the scheme of things this is still quite a bargain. On eBay they are usually priced at more than $700 each.

Oh, well. I still have my doorknobs. When they come up for bids Elliot announces that not only have there been calls about them, but bids have been left, and there are bidders on the phone.

They go for $175.

Elliot's auctions have become the hip place to be on a Sarasota Sunday afternoon. They're like group therapy for collectors, designers, and wannabe designers. Imagine—one by one, beautiful and unique objects are held up for you to admire. You learn a little about each one, and why one is better than another. You also learn an awful lot about price. It's always thrilling to walk into an antique store in St. Pete and see something that was sold at Elliot's last week, only now marked up 200 or 300 or even 700 percent.

I did end up with the lamps. If there is one thing I've learned about Sarasota, it's that only a fool pays more than $25 for a lamp. Walk into the Woman's Exchange any day of the week and you can take your pick of high-quality lamps at that price. So I decided I would go as high as $40 for the two. Somehow, in the heat of the moment, that $40 turned into $65, and that's what I got them for.

The one I thought I liked the best looks awful in my living room. It has a strange similarity to a giant Oscar, and it's about five inches too tall for where I want to put it. But the other, the Parzinger-style one—I love it. So simple, so delicately substantial, so impeccably tasteful. It's my new favorite possession.

And as for the doorknobs, now I'm glad I didn't get them. They might have been more trouble than they're worth.

Auction Smarts

Elliot lays down the rules. Everything is sold "as is." "I don't guarantee anything," he said. "If you're smart, you will examine it carefully."

Auctions are generally held every other Sunday at 1 p.m. Mid-century modern auctions are every six weeks or so. Check auctionzip.com for the schedule, directions, and pictures of upcoming items. Bernstein's ID number is 8290. Or call (941) 351-3002.

Make sure you examine carefully the items you're interested in, either at the preview the day before (usually from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m.) or during the hour or so before the auction. This will also give you time to do Internet research.

Registration is simple; all you need is a driver's license.

Buyers pay a 13 percent premium above the gavel price. This is reduced to 10 percent for cash

or checks.

Food is available. There's a hot dog truck out front.

The auction can easily last past 5 p.m., by which time most of the crowd has drifted out. If you stick around late you can often get incredible deals.

Click here to read Bob Plunket's "Home of the Month" in our January issue. >>

This article appears in the January 2014 issue of Sarasota Magazine. Like what you read? Click here to subscribe. >>