Turbo Charged: Racing at Sebring International Raceway

On a blistering hot day at the Sebring International Raceway—just an hour and a half from Sarasota—a driver puts his Porsche Cayman into the wall at 130 shrieking miles per hour. From the relative safety of pit lane I watch as it explodes into a Bruckheimerean fireball, complete with billowing black smoke and the worrying stench of burning electricals, and then the fire truck and ambulance crews are swarming the scene faster than you can say next of kin.

I am unnerved by this not only because I have never seen anyone die in front of me before but because I am here for my first-ever race car driving experience, and I happen to know the following things: The Cayman has a measly 260 horsepower and is world famous for engineering that conduces to poise and stability. Its driver has the Crackerjack reflexes of a 32-year-old. He is also the lead racing instructor at today's Porsche Club of America event.

My 911 Turbo, on the other hand, has over 500 horsepower and is globally renowned for engineering that results in waywardness and bloodlust. I have the laggardly reflexes of a sleep-deprived 42-year-old who needs but vainly refuses to purchase eyeglasses. And the only expertise that I have with Porsches is the innumerable hours I spent ogling the many posters on the many walls of my various childhood bedrooms. Oh, and as the wrecker hauls away the smoldering hunk of metal formerly known as the Cayman—and as the ambulance pulls away—the man on the PA speaker announces an additional bowel-loosening fact:

I'm up next.

As I buckle into the 911, don my helmet, wipe sweaty palms in sweaty armpits, and pull into line with the other novice drivers, I am overcome with a man-on-the-gallows kind of protonostalgia for the present—and maybe last—minute of my life, so I give myself a few precious moments to take in the scene around me.

The stands are frothing with giddy children and watchful parents; guys in shorts that are way too loose flirt with girls in jeans that are so tight that their iPhones keep trying to squirm out of their back pockets like jailbreaking baby marsupials; a few rebellious teenagers have peeled away from their driver safety course that is happening on one of Sebring's other tracks to stare, agog, at what is about to occur; and a red-haired kid on an electric scooter is gadflying through the parking lot thronged with all of the Porsches that have instantiated a lifetime of worshipful daydreams.

There are battle-weary, spavined 944s that have somehow survived from the 1980s, a few big-buttocked 928s, welterweight Caymans and Boxsters and scores of 911s of every incarnation, including at least a dozen modified GT2s and GT3s, Porsche's howling mad race-cars-for-the-road.

And then, of course, there is my canary-yellow 911 Turbo. Now, to me, driving any 911 whatsoever would set a record in the annals of boyhood fantasy. I have dreamed about these cars so fervently and for so long that I would happily sell any semi-vital organ—I'm looking at you, spleen—just for the chance to drive one nonfeloniously around the block. Being able to drive a Turbo on a professional racetrack as fast as my courage will allow is intoxicating. Exactly how fast can it go, you're wondering? Think of it this way: By the time you're done reading this sentence, you've already gone from zero to 60 miles per hour. Before you can Google "Sarasota chiropractors specializing in whiplash" or maybe "home remedies for PTSD" you have already covered a quarter mile.

And if you have the gall to keep the gas pedal pinned, what you will see blurring past your window won't be a familiar terrestrial landscape; it will be the space-time continuum.

Crying uncle.

What makes the whole enterprise even more exhilarating, of course, is the proximity to death. All 911s are rear-engined, which means that the weight of the car is essentially, and stupidly, over the back bumper—a design choice that endows 911s with the balance characteristics of a bowling pin—which in turn means that when you take a hot corner the car wants to slide out, spinning ass-backwards in a whirligig of death, and smash catastrophically into the nearest available object.

So driving one of these is not exactly a stress-free experience. And my Turbo in particular carries an extra payload of anxiety because it was loaned to me for this article by a guy who a) has never met me before, and b) bought it as a means of bonding with one of his sons, not just for sporty automotive fun but as c) a heartfelt commemoration of another son who had died tragically.

As I contemplate the manifold fiery ways I could destroy this beloved six-figure family heirloom, the grand marshal waves the start flag and then we're off. My instructor, who is ensconced beside me in the "angel seat," has told me over and over that I will not impress him by going fast today and that I will only impress him by being smooth—"Smoothness is speed," he told me at breakfast at 6 a.m.—so, naturally, I take the very first corner at such a necksnapping velocity that the car experiences a total and complete loss of traction.

The wheels judder violently, the whole car hunkers down, the tires wail in outrage, and the smell of burning rubber floods the cabin. We are now going so sideways, at roughly 100 miles per hour, that my front view, which would normally be through the windshield, is now through the passenger window. I can see the rumblestrips approaching. I can see the grass approaching. I can see the scarred wall approaching. If I were thinking clearly, I might also see a sizable lawsuit approaching.

As I screech wildly toward crunchy Newtonian doom I can't help wondering, with the clarity of the near death experience: How did I get here?

There is a tradition in my family of shirking responsibility, whenever at all possible, for calamitous events of your own authoring, and so I am tempted to blame my teacher, who has a flowing gray ponytail, the spiritual charisma of a lama, and the matinee-idol name of Guy Covington. Alas, however, Guy is also a pillar of the automotive community, an esteemed racing instructor and totally unculpable. In fact, his instruction is probably the only reason I'm typing this sitting upright at a desk and not reclining painfully in one of those contortive hospital beds that smell like freezer burn.

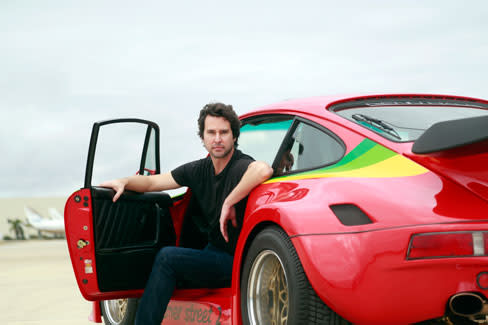

Even discounting the happy results of his life-saving instruction, Guy is an extraordinary person. He has worked for the late, legendary movie mogul, Lew Wasserman of MCA; he opened a wildly successful computer business in Marin County at the vanguard of the tech revolution; and, until a devastating motorcycle accident, he was a highly recruited baseball player with a shot at the majors. Then, in 2002, Guy sold his computer business and moved from Sausalito to Sarasota, where he hired a Porsche tech and opened a repair and high-performance shop to support his interest in racing.

Saying that Renn Haus is just a shop, however, is like saying the Great Pyramid of Giza is just a family funeral plot; Guy's Clark Center location is more like the headquarters for anyone in the Sarasota area who cares about German cars, or racing, or automotive lore. It is a mecca for all manner of enthusiasts—from high school kids who scraped together enough money for their '70s-era Beemers to millionaires with their near-priceless collectibles to racers with dedicated track-day beasts—who all need to have their cars repaired or maintained or enhanced, sure, but who also need a place to come and have a carklatsch. Such is Guy's reputation amongst the petrolati that he has never placed a help wanted ad for workers; every single one of his employees—including Steven "The Doctor" Jones, who is such a virtuoso that he listens to the cars he works on with a stethoscope—have sought him out, often from places as far afield as California and Germany. He has a fanatically devoted band of customers, too, who all regard Guy with the affection and reverence that graduate students have for their most august professor.

Today, however, and to me, Guy's most important role is as a conduit to some of the world's most brutally fast cars. There is the borrowed 911 Turbo that I will soon launch ruinously toward the retaining wall, but there is also a C63 AMG, a car that is as starkly purposeful as a scalpel, and a massively heavy but savagely quick black S600 that is downright Darth Vaderean.

And then there is the Kremer.

O, the Kremer. This is a car that could just as easily be in a museum as on the track. It is a very specialized, hand-built 935—essentially a slant-nose 911—and this example in front of me is one of six ever made. Such is its rarity, in fact, that no one even makes tires for it anymore; you have to call up Pirelli and explain to them that you own a Kremer, and then, presumably after toasting your gusto with grappa, they will send you a set of custom-made tires for a thousand dollars—per tire.

The Kremer was made in 1984, a time when aerodynamics operated less on science than on hunches. In the case of the Kremer, it looks like the engineers decided to use a policy of saturation; everywhere you look the Kremer is all vents and gills and ground effects and muscular bulges and scimitar-curves. Its rear end is dominated by the familiar whale-tail spoiler and intercooler, its side-view mirrors are abbreviated little nubbins, and the front is so low to the ground that when Guy passes over a sadly flattened piece of mammalian roadkill on I-64, it nerfs the Kremer's lower lip. All these design elements combine with the radical red/green/yellow color scheme to make it look menacing and race-ready—I bridle but finally concede she has a point when a female friend of mine says that it looks like a "Jamaican rocket"—and when Guy invites me to hop in for a ride and fires it up, the engine explodes into a sputtering din like grease popping furiously in a hot skillet. When I hear it I get the same jolt of adrenaline that our semi-sapient forefathers felt when they heard a saber-tooth tiger growl.

I am simply genetically coded to respond to this sound.

Guy, perhaps sensing my agitated line of thinking, looks over at me from the driver's seat of the lathering Kremer, and smiles.

"Ready to go have some fun tomorrow?"

I express my answer in drool.

Guy and I don't make it to Chateau Elon until after midnight the evening before the race and, for some incomprehensible reason, the hotel's fire alarm goes off at around 4 a.m., after which I maddeningly cannot get back to sleep. So it is on only a few hours of restive sleep that I head down to the track with Guy to register and attend my classroom lecture on safety, etiquette and high-speed physics, and where I learn, after years of supremely uncool mispronunciation, that the brand is a bisyllable: POR-shuh.

I am also informed about the hierarchy of tolerance levels to hooliganism. "One wheel off the track," says the orientation leader, "is O.K. Two wheels and you get a warning. Four wheels we consider a learning experience. But put four wheels off the track a second time and you are yanked for the day," he says, looking sternly, and clairvoyantly, at me.

The last thing the instructor tells us is what all the different colored flags mean. It happens so fast that I forget nearly all of them—except, that is, for the red flag.

"This is basically the disaster flag," he says. "It means something terrible has happened and every car needs to stop at the nearest corner immediately." Then he looks reassuringly at us. "But don't worry," he says. "You won't need to remember this one. I've been doing this for 30 years, and I've only seen the red flag come out one or two times."

Of course, 30 minutes later the red flag comes out waving when the doomed Cayman hits the wall and then, next thing I know, I am sitting in the starting line with the other novices. As I white-knuckle the wheel of my Turbo I try to focus on all the things Guy has told me about how to get around the track unfatally.

The most important thing I recall is the proper way to take a corner. The mantra is "slow in, fast out," which means that you need to brake hard—really hard—as you approach the corner so you can accelerate smoothly through it. The most surprising thing about the whole cornering process is that as you are braking, you want to give the brake pedal a very last-second stab right before you cut the wheel. This is to make the whole car lurch forward right before the turn so that the weight of the vehicle is over the front tires for the purposes of maintaining grip. It's one of the chief pleasures of racing to get the right combination of aggressiveness and prudence, urgency and control, and pedal firmness and restraint.

Also, Guy told me that unsettling the balance of the car for any reason will result in the loss of traction, so as you enter the corner you must already be in the right gear for the exit. If you find yourself skidding out of control, however, you need to resist the urge to counter steer. You must not death-grip the wheel. Do not brake. And although it's a hard and counterintuitive pill to swallow, you should never, ever let off the gas.

In roughly 10 seconds—when I will lose traction so disastrously around that first corner—this will be the most important thing in the world to me and my corpus.

The fateful starter flag waves and I tell myself, for the thousandth time, to be moderate. To focus on "smoothness," as Guy has exhorted me to do. But—the famous "but"—I am now behind the wheel of a freaking 911 Turbo, which means that my entire worldview has now been reduced to just two philosophies: I can floor it or not floor it.

Guess which one I do.

Everything is fine for the first, oh, hundred feet. My body is thrown into my seat, the wastegating turbo making a sound like Godzilla lisping vowels angrily, and the crush of acceleration is so savage it feels like the soft tissues of my body are deforming. And that's all great.

But then I get to corner No. 1, cut the wheel, and—as you know—my tires come unstuck from the pavement and I'm suddenly going sideways toward the wall. Then, at the very last zeptosecond, as the beautiful, expensive, heirloomic Turbo careens—skates—toward the wall, the whole car suddenly snaps violently to attention and straightens crisply out, its tires mere millimeters from the grass. This is so shocking and so vertiginous it is as if the car is obeying the command of some fairy godmother of physics. Then turbo hits and I am launched down the straight toward corner No. 2.

I can only imagine what the people behind me must be thinking.

I also wonder why Guy isn't screaming at me through my earpiece. I am pretty sure I have it coming. But I don't get it. Not, that is, until I unwisely say, "Hey, sorry about that. I just—"

Upon hearing this, Guy interjects with an unprintable outburst that I will paraphrase here as, "You fouled up that corner but you don't have the time to worry about it—you have another corner coming up! You can't afford to waste one more second talking about what you messed up! Concentrate on what's ahead of you or we're going in for the day!"

At first I am taken aback by the scolding but then I realize how right he is. I also realize that this is one of the things that makes racing so profoundly philosophical: It takes a grinding platitude like "focus on the future, not the past" and makes you appreciate its essential elemental truth. To make a teensy emendation to the words of John Keats: Axioms of philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our adrenaline, and in racing, the idea of focusing on the future isn't just a mantra of nifty self-improvement.

It is a matter, quite simply, of life and death.

Feeling spiritually bettered and both profoundly Zen and electrified at the same time, I keep racing. I have several sessions in the Turbo over the course of the day—sadly, I get none in the Kremer; the privilege of piloting that expensive brute is reserved only for drivers of Guy's accomplishment—and I keep improving with each lap. I start to relax my grip on the steering wheel so that it is unclenched and, like a fencer's grasp on the blade, so light that it verges on negligent. I learn to breathe on the long straights, reset my focus, and refresh. I become more mindful of the flags and how to take the best lines for each corner and how to shift the weight of the car skillfully and smoothly and—drumroll, please—uncatastrophically.

An unexpected and very welcome real-world corollary of my improving skill on the track is that when I leave Sebring and go about my automotive business on regular roads, I am a far better driver—more alert, more discerning about the lines that I take in corners, more anticipatory, and certainly safer. My car feels less like a car now than a 3,000-pound dancing partner.

A happy bookend to the weekend: At the end of the day I find out from some race officials that the driver of the Cayman somehow escaped his crash without any serious injuries.

So, to the list of recommendations for a high-octane weekend getaway at Sebring—philosophical epiphanies, the feral Valkyrie-screech of internal combustion, improved street-going safety, and all-around endorphinated good fun—we can also add zero fatalities.

Dragstrip Dreams

In the fast lane at the Bradenton Motorsports Park.

The Bradenton Motorsports Park, only 15 minutes from Sarasota proper, represents by far your best bang-for-internal-combustion-buck. For less than $20 you get admission to the facility with its twin dragstrip tracks—newly dressed in 2½ inches of asphalt for a cost that management will only describe as "healthily six figures"—which entitles you to all the spectator areas and to as many runs as you want to make.

The drag strip is an ecosystem all its own. At dusk on the night that Guy and I show up, the place is nearly empty, but before you know it the lot is filled with every kind of car conceivable, from sleeper-class econoboxes to dead-stock American muscle cars to nitrous-injected dragsters that shoot flame out of their exhausts. High school girls gather in gangs against the chain link fence that borders the track, cutting salsa steps and cheering for their boyfriends as they rev their engines and smoke their tires and streak down the strip. Males of every age wander through the clots of sports cars and hot rods, which all have their hoods popped like bodybuilders pulling back their shirts to reveal six-packs. Everywhere you look—on billboards, on bumper stickers, on denim apparel—are images of American flags and bald eagles.

The air smells of burning rubber and gasoline and cheap perfume and the concession booth's deep fryer, and despite the all-around bonhomie of the racers there is also the charged, hormonal feeling of a battlefield.

Finally it's my turn. I strap into the C63 AMG, pull into my lane, and warm my tires by smoking them on the watered-down asphalt. As I approach the start line I get scolded for leaving my window down. "Gotta keep 'em up," the nice man with the hose tells me in an effort, I am nearly positive, to be reassuring. "That way if you wreck and roll the car all of your limbs stay inside the car."

Then the start lights go orange-orange-orange-GREEN, and I and my limbs are off.

My first run isn't bad. My second is slightly better. The tricky part is the launch, and after experimenting with different levels of aggression—too much wheel spin means you're slow because you're not putting down any traction and no wheel spin means you're not trying hard enough—I become skillful enough to be nearly competent. I drive both the C63 and also the baleful, hulking S600, which, thanks to Guy's fettling, has nearly 1,000-foot-pounds of torque at the flywheel and a zero-to-60 time of 2.9 seconds—faster than nearly anything this side of the Space Shuttle Endeavor—but despite my many runs, I never beat, or even endanger, Guy's quarter-mile times in either car.

Still, I do well enough that by the end of the night I get an approving nod from the grizzled fellow who gives you your time on a print-out after you pull off the strip, which makes me feel as if I have been dubbed a knight of the Most Noble Order of the Motorpark.

Going fast in a straight line will never be as interesting as going fast around corners, but the strip has terrific aw-shucks charisma and they have a great schedule of competitions. Upcoming events include Grudge Match Night, Import Face-Off, US Street Nationals, and an any-vehicle-goes competition called Street Heat.

For more information: bradentonmotorsports.com, (941) 748-1320