Best-Selling Author Randy Wayne White Crusades to Protect Tarpon

To hear author, restaurateur and angling activist Randy Wayne White tell it, as he recently did at his Doc Ford's Rum Bar & Grille on Sanibel Island, all of us Southwest Floridians are here because of a fish. Because of its fight, the lightning-quick way it rolls and leaps when it strikes, and because of its strength and beauty. That fish is Megalops atlanticus, an archaic, cow-eyed, thick-jawed feeding machine that can reach eight feet in length and weigh 250 pounds. Tourists call it "tar-pon." The rest of us say "tarp-in." No matter how you pronounce the name, the tarpon with its silver-dollar scales has always meant money, and that's at the heart of a recent controversy that embroiled White and the organizers of a high-stakes fishing tournament down in Boca Grande.

"When the first tarpon was landed on rod and reel in 1885 in Sanibel," White, sitting before an opened laptop in his bar where I've caught him writing, tells me, "it made headlines. This was the only big game fish that one could land in a rowboat. Industrialists began to come to this pioneer mangrove coast. Thomas Edison wanted to catch a tarpon, he came here. The Charlotte Northern Railway extended its service to Boca Grande; that began hotels. The tarpon changed the destiny of this coast."

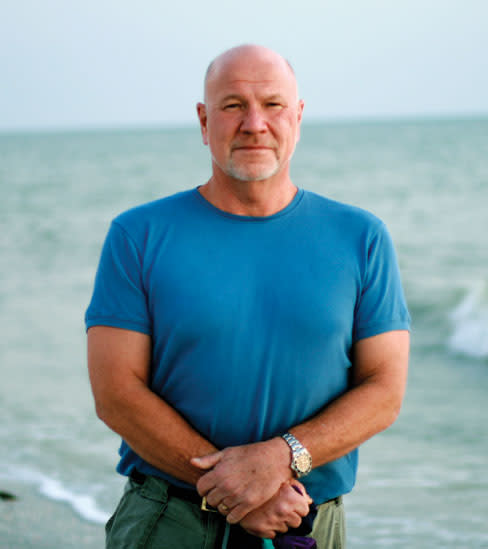

White is an amicable guy, a youthful 63, a baseball-playing Midwest farmhand who came to Sanibel in 1972 with a high school degree and a yen to write. He earned his salt as fishing guide and adventure magazine columnist, raised two sons and wrote every day. After churning out 18 novels under pseudonyms, he finally found a character, a former NSA agent and marine biologist named Doc Ford, which led to a best-selling series of thrillers, the first of which was 1990's Sanibel Flats. The series' popularity has allowed White and his business partners to commercialize the Doc Ford name into three restaurants, a hot sauce line, T-shirts and golf visors. And last year, White used his literary muscle to weigh in on what many here see as the ugliest chapter in the tarpon's history.

In a special commentary in the Tampa Tribune in April, White wrote, "In the early 1990s, when tarpon tournament purses in Boca Grande Pass climbed to $100,000 or more, two local anglers revived an old poaching technique that guaranteed they would boat tarpon and also fill their pockets…. Among guides, 'jig fishing' became the accepted euphemism for snag fishing, but always in a wink-wink sort of way because boating fish is key to making money…. The technique wasn't illegal, but most of us knew it wasn't ethical…How do I know this is true? Because, as a fishing guide, I did it."

The "Boca Grande jig" masquerades as a traditional jig hook but is designed to sink steel into tarpon even when the fish aren't biting. When a fish strikes a true jig, it's hooked inside the mouth; with the belly-weighted Boca Grande jig, an angler drops the hook to the bottom, waits for a fish to bump the line, then reels as fast as he can. The line "flosses" beside the fish, often sliding through its gill plate, and the heavy jig streaks up like a fist and punches its hook into the fish's face or body.

"Snagging is taboo in the world of sport fishing," White tells me as he leads me around his restaurant. "It's the equivalent of harpooning or using dynamite." The island-themed Doc Ford's is packed for dinner, the genteel patrons dressed in polos and khaki. White spends a few minutes chatting with two couples from Kansas City, Dee and Frank Mana and Kathie and Phil Ziegler, who tell me they're here because of the Doc Ford series. White signs a book, "Dear Dee, Doc's Pal!," then urges the group to, "Try the hot sauce."

Out in his truck, White riffs on the surreal success of his books and the restaurants, which has come later in life for a writer whose early days often did not include hot water or A/C. "I did many years with no safety net," he tells me as we pause to let some beach tourists scamper across the road. "Every day now, it just feels dreamlike. Peter Matthiessen [the National Book Award-winning author of the Watson Trilogy] gives me a hard time about being commercial. He says, 'So, Randolph, are you going into real estate?' I say to him, 'A Killing Mister Watson oyster bar. Think of the T-shirts.'"

Soon we're at Doc Ford's on Captiva Island, a cavernous 400-seater, and White winds his way to the back bar, greeting fans and staff alike. At the bar, I ask a red-haired lady sipping a cocktail if she reads the Doc Ford series. She takes a hard look at the man beside me and says, "Are you the Randy White?"

"If you knew me, you'd run like the wind," he tells her. Soon, he's posing for a picture, and then we're talking tarpon again. White says, "When they first started using [the Boca Grande jig], I had a client who would book me every year during tarpon season. I told him about it and he said, 'Let's go out and try it.' I wired a very heavy weight, probably three ounces, to the hook. He landed two fish; one was hooked under the lateral fin. They're almost all hooked outside the mouth [using the Boca Grande jig]."

The practice might have continued if not for the 2003 entry of the Professional Tarpon Tournament Series into Boca Grande Pass. Hosted by Sarasota's Joe Mercurio, the PTTS and its sister series, the Women's Professional Tarpon Tournament, have the richest tarpon purses in the world. This year, they'll offer more than $500,000 in prizes.

From the beginning, the PTTS drew criticism. "The Pass's characteristics are such that the tarpon are contained in an area and must stack up," explains White. "To snag fish effectively, you need a very fast boat, and during the tournaments we're talking a hundred or more. It's day after day of these high-speed pursuits of these fish who are there to feed and fatten and do this little-understood ceremony that's prelude to their mating. It's just a circus."

Like White, the PTTS and Joe Mercurio are commerce-savvy, though the tournament targets a different audience. Its marketing videos highlight the very things White and other PTTS critics abhor: teams of sponsorship-clad fishermen in sponsorship-wrapped boats, all in a frenzied pursuit of fish. The videos' background music is high-octane synthesizer, the feel is NASCAR. "The PTTS pits 50 teams in a head-to-head gunnel-to-gunnel battle," the announcer intones in the 2010 video. "The playing field can only be described as controlled chaos." The PTTS TV series reaches 42 million viewers and is co-hosted by a Sarasota-based blond bombshell, Sheli Sanders. Prominent in the videos are bull and hammerhead sharks chomping through tarpon even as the anglers reel them in.

What White and groups like Save the Tarpon of Boca Grande Pass argue is that the tournament uses the doctored jig and harasses the fish at a critical time in its breeding cycle. Bowing to pressure from Boca Grande guides, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) conducted a $200,000 foul-hooking study from 2002-2004. Surprisingly, the FWC did not find that the Boca Grande jig was hooking tarpon outside the mouth.

White says: "In the study, 75 percent to 80 percent are hooked in the mouth. But people did not ask what constitutes 'mouth.' The study's definition is essentially this: Any bone in the tarpon's head connected to its mouth [is its mouth]. The study has done more to harm tarpon in the last 10 years than any number of tarpon fishermen."

For 10 years, the study's critics struggled to keep the issue before the press while the PTTS flourished and grew, and the acrimony between the two camps developed into a wasps' nest. Both sides threatened to boycott the other's businesses, and important FWC votes required police presence.

Fast forward to the spring of last year and what happened next reads like the plot line of one of Randy White's thrillers. As persistent as his marine biologist, Doc Ford, whose doggedness is the mainstay of the novels, White read every research study on the tarpon ever written. His aesthetic interest in the fish also remained as great as it does for his signature character. In Sanibel Flats, he writes, "[Ford] noticed something in the distance—something glittering, energized, rolling across the calm like a boat wake: a school of tarpon coming toward him; a dozen or more fish moving in a tight pod. Their big tails were throwing water; their chromium scales threw sunlight…. Ford stood watching, loving it."

On May 8, 2013, a man who had spent much of the past decade out of the country wrote a letter to FWC Chairman Kenneth Wright, in which he said he wished to clarify his involvement in the 2002-2004 study. He wrote: "Recently I was contacted by Randy White and [Boca Grande angler] Bill Bishop in regards to my involvement in [the study]…I have to admit I have not followed this issue…. I was contacted by the FWC sometime around 2003-4 because of my 2001 research publication [about tarpon jaw morphology]. My recollection of that phone call was approximately a 30-minute discussion where I was [asked] whether it's possible these jigs' hook placement in the clipper could be the result of feeding behavior."

The man was Dr. Justin Grubich, associate director of biodiversity informatics at Chicago's Field Museum. As first reported by the Boca Beacon, Grubich was the story's missing link, having been away studying fish in Egypt for years before serving as a science advisor to Hillary Clinton and a foreign affairs adviser to President Obama's Cairo Initiative. He'd only just returned to the Field Museum when White found him by using a reactivated museum email account. Grubich was surprised to learn that language he'd used during that 30-minute conversational phone call had somehow become part of the study's foundation. He continued in his letter, "[T]ruth be told [the Boca Grande jig issue] was not effectively communicated to me by the FWC representative during the interview…I would like to clarify some misrepresentations of my testimony."

Grubich explained that unlike how his opinion was interpreted in the study, he did feel the adulterated jig could snag tarpon. Soon after, USF's Dr. Phil Motta, who had also contributed to the study, joined Grubich in requesting that his original comments be withdrawn. In June, the FWC voted 4-3 to consider revised definitions, and in September, it voted 7-0 to ban the Boca Grande jig. The rule took effect on Nov. 1.

White tells me of the moment he found Grubich, "Had I used that as a plot line in one of my books, the reader would have said, 'This is not to be believed, it is too coincidental.' I wish I believed in kismet because in that case, I really began to wonder."

Anti-snagging activists say that Kathy Guindon, the FWC researcher who made the 30-minute call to Grubich, had a conflict of interest during the study. According to Save the Tarpon's Tom McLaughlin, "Kathy had a relationship with Robert McHugh, the prior year's winner of the [PTTS] Tarpon Cup. A lot of her data was based on her relationship with him. What she did was form her own opinions and pull quotes from her conversations with these scientists that supported her opinions."

Although she would not address the conflict of interest issue, Guidon responded to other questions in an e-mail: "I stand by the study…I can only speak for myself, and I would not have explained management issues of Boca Grande Pass to [Grubich and Motta] as that is not why they were contacted…I do not believe [Grubich's] words were taken out of context."

The PTTS also responded to questions via email: "[We] disagree with the [decision to ban the Boca Grande jig]. This ruling sets a dangerous precedent that the rights of anglers to fish with a variety of fishing lures can be taken away without any scientific or biological evidence. [It] will have little or no direct impact on the PTTS. Our 2014 schedule is set, and our events and television show will continue."

But Randy White isn't as certain. "If that hook is not a snagging device," he tells me, "the tarpon will still hit [legal fishing hooks]. If it is a snagging device, then they will not hit and he won't have any footage. Tarpon are by and large crepuscular [twilight and after-twilight feeders]. Are you going to use night vision video? It's got to be during the daytime. If not, you're not getting these images of hammerhead sharks coming up and eating them, which is a major part of what he does."

This May, the tarpon will stack up in Boca Grande Pass like thousands and thousands of silver bars. Whether the PTTS can continue to cash in on them remains to be seen.

"Doc Ford key chains?" I suggest to White as we part company. He grins and tells me, "Key chains are a great idea."

Contributing editor Tony D'Souza has won a number of awards in the past year for articles for Sarasota Magazine. He was a finalist for the Society of Professional Journalists' 11-state Green Eyeshade award and the SPJ's Sunshine State award for Investigative Reporting. He also won the Florida Magazine Association award for Best Investigative Reporting.