Behind the Fake: An Interview with Author Clifford Irving

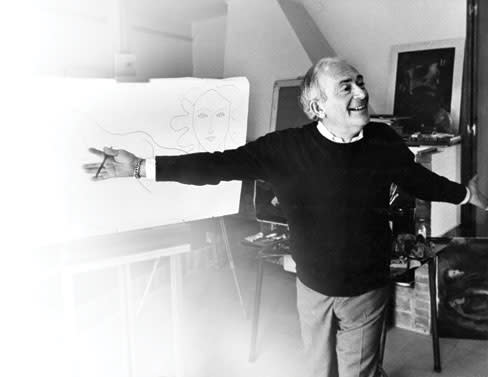

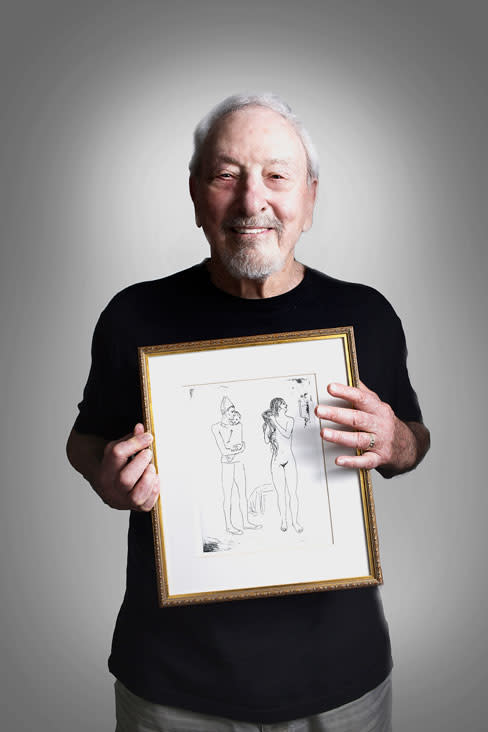

Author Clifford Irving may be best known as the man who faked an autobiography of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, eventually spending 17 months in prison after exposure of that publishing hoax in the early 1970s. But Irving has had a long and colorful career as a novelist and screenwriter both prior to and after that, even writing his own story on the Hughes affair, The Hoax, which was turned into a film starring Richard Gere as Irving.

Perhaps that history gives Irving, now 83, insight into the world of the artists highlighted in the current Ringling Museum exhibition, Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World. After all, Irving (who recently moved to Sarasota with his wife, Julie) wrote the book on art forgers, so to speak, with the 1969 book Fake! The Story of Elmyr de Hory, the Greatest Art Forger of our Time. (De Hory is one of five forgers whose work is featured in the museum show, on view through Aug. 3.) We sat down with Irving at his Sarasota home to ask a few questions about de Hory and their relationship.

Q. How did you come to meet Elmyr?

A. He was a friend of mine and my then-wife, Edith. He knew everybody in the café life of Ibiza [the island off the coast of Spain] where we lived in the 1960s. Many of us artist ex-pats were poor, to varying degrees, and I remember I once asked Elmyr to lend me $100, telling him I'd pay him back when a check from my publisher arrived. He'd heard that story so many times before from so many others. With great reluctance he loaned the cash to me, and he was flabbergasted when I repaid the loan a few weeks later. Tears came to his eyes. That's because he was always being used; he was gay, and he liked young men, so he had to pay, one way or another, all the time, for friendship and love.

Q. And how did you end up writing the book, Fake!?

A. When he was accused of forgery on a worldwide scale, he came to me and Edith for help. First, for shelter. Then, he needed the money that would come from sales of a book about his exploits.

Elmyr was not a clever businessperson. One evil man [Fernand Legros] and a young friend of Fernand's exploited Elmyr for years by selling his work worldwide, making millions and doling out small amounts to the struggling artist, who was dependent on them and also afraid of them. All Elmyr wanted was to live quietly, do his own work, give good Hungarian paprika dinner parties—he was a superb chef—and sell an occasional fake to keep the wolf from the door. By the way, he didn't copy, he faked…there's a difference. He did works in the styles of certain artists, principally the French post-Impressionists, and his fakes sold for a fair amount of money.

Q. Do you know how his career began?

A. Elmyr was a refugee from Hungary, who had studied art in Paris under Leger. He always said he came from an upper-class family, and would tell endless stories of his mother gliding down the grand staircase of this-and-that-sumptuous villa wearing fabulous gowns. That was all fiction; it turned out Elmyr was actually from a modest middle-class Jewish family. But he was a great raconteur. No doubt his imagination saved his life. He told me that in World War II he spent time in a concentration camp where he painted a never-ending series of flattering portraits of the commandant and his family in order to stay alive. The commandant let him go just before the SS was about to liquidate the camp.

At the time I wrote the book, Elmyr was in trouble. A Texas oil tycoon, Algur Hurtle Meadows, had bought more than 40 paintings from the two villains who were selling Elmyr's works. Meadows donated them to SMU, but first he showed them at a gala party in Dallas. When you can view Elmyr's paintings in a group—Dufy, Matisse, Picasso, Modigliani, etc.—there's something more obviously wrong with them than when seeing just one or two. The discerning eye can see that the same hand guided the brush.

A group of top art dealers, all of whom admitted they'd been previously duped by Elmyr and his high-pressure sales force, came to the show, where the truth struck them like a hammer blow. And suddenly the art world was in turmoil.

Paintings disappeared from the walls of art galleries and museums and were hurried off to back rooms and cellars to weather out the storm. Worse, the French police launched their own investigation into his work. Elmyr was frightened. He came to me on Ibiza and said, "I'm going to tell you who I am and what I've done, and you'll be shocked." Well, I wasn't shocked. I was surprised and amused. He proposed that I write some magazine articles and a book that would help with his legal fees and give him a nest egg for the dangerous future. I called my publishers in New York, McGraw-Hill, and they snapped it up.

Q. What happened after the book came out?

A. Alas, our friendship ended. Most people thought my portrait of Elmyr was sympathetic. I certainly meant it to be. But Elmyr didn't like that I quoted some French dealer calling him "a charming crook." He didn't appreciate that kind of raw truth. The tale, in cold black and white, did not flatter him sufficiently. He demanded I make changes. I refused. He stopped speaking to me.

The book got excellent reviews. But Legros sued the publishers for libel; he had a ton of money, could afford good lawyers, and the publishers had to hold back the book pending a court ruling. Sales dried up in the United States, England and France simultaneously. It took years for Fake! to be republished, even though we won all the cases except in France, where we abandoned it because it was too costly.

Personally, I loved Elmyr as a friend—although I didn't trust him—and I portrayed him as a sophisticated, elegant, intelligent, sad and exploited man. I understood his plight. He was one of my first gay friends, and he often talked about the problems of being an older gay man. That was foreign to me before then.

Q. Tell me about the Orson Welles movie about De Hory, F for Fake. Were you involved in that?

A. Yes, it was originally a BBC documentary, and the BBC hired me on Ibiza to be their intermediary, a kind of point man. As a result, I owned part of the profits. I like Orson's movie a lot—it was unique, it's stood the test of time, and it's become a cult movie. But only the first part focused on Elmyr and me as iconoclasts in the art world. The last part is some silly business about Orson and his beautiful Hungarian girlfriend who has a fantasy relationship with Picasso.

Q. And there's another film version of the story possibly coming out soon?

A. The movie rights to Fake! are under option to a top independent company called Anonymous Content and a producer named Steve Golin. They asked me to write the screenplay, and I did. They told me, "We love it, it's great." But the English director they hired wanted to make it darker, a tragedy instead of an absurd comedy, and I couldn't come to terms with that vision— which I find, ironically, to be fake—so AC has hired another screenwriter to write a second draft. They want Johnny Depp or Javier Bardem to play Elmyr. I hope the movie gets made.

Q. What do you think motivates someone like De Hory to fake art work?

A. It's a World War II refugee mentality. He never thought he'd be rich, but he needed money to survive and still keep some prideful identity as a painter. Survival is the name of the game. He'd justify it by naming all the great artists in history who had copied and faked. He knew his art history. There were many. When they were young and poor, they had to eat.

Q. His life came to a sad end, with suicide. Was that inevitable, do you think?

A. No, I don't. He was famous by then to the point where his oils signed "Elmyr" were selling at good prices. He could have fled to South America and begun a new life. The story I heard from reliable sources was that he had concocted a plan with his then-boyfriend to fake his death—Elmyr would take an overdose of sleeping pills at five minutes to 10, and the boyfriend was supposed to come home at 10 sharp to save Elmyr's life in a timely manner. But he didn't come back until midnight. And then it was too late.

I do know that Elmyr was about to be extradited to France, and he was fearful that Fernand Legros would have him killed in prison. I knew Legros—a man with the scruples of a sewer rat, and he was certainly capable of murder. Elmyr thought that if he nearly committed suicide, the Spanish authorities would take pity on him and cancel the extradition to the Bastille. It was a naive concept. The Spanish government wanted to get rid of Elmyr. He was an embarrassment.

Q. Any thoughts on the mindset of a forger like De Hory?

A. I'm sure there's a certain challenge embedded in his psyche, an anti-establishment attitude. A yearning for recognition. You know, "I'm as good as Picasso because I can sell signed Picassos and the pompous experts can't tell the difference. I'll show these idiots what fools they are and what a genius I am." And, you know, he was a genius, in his way. There have been many art fakers since—it's become quite fashionable—but none as good as Elmyr.

Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World presents pieces produced by five talented forgers: Han van Meegeren, Elmyr de Hory, Eric Hebborn, John Myatt and Mark Landis. There are 60 works of art on display, including some of the original pieces the forgers copied. For more info, go to ringling.org.

Interested in Clifford Irving?

In a unique eBook event, he's recently published 18 of his books on Amazon's Kindle.com and Barnes & Noble's Nook.com. Among them is Fake! The Life of the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time. The Chicago Tribune called Fake! "the wild, true story of three men who raped the art world . . . one of the most sophisticated suspense sagas of our time."

A sampling:

Final Argument. A Sarasota and Jacksonville-based legal thriller about a district attorney who, 12 years after sending a murderer to Death Row, returns to the same courtroom to try to save that man's life. The New York Times said, "What a wonderful piece of storytelling."

Daddy's Girl: A True Legal Thriller of Texas Justice. A Houston lawyer and his wife are murdered by an ex-Marine, but an ex-stripper turned detective solves the case. "Fascinating ... Few writers could have pulled together so insightful a work." — Austin Challenger

Trial: a Legal Thriller. A lawyer defends two accused murderers at the same time, one a former beauty queen, the other a homeless illegal alien. The L.A. Times wrote: "Made by a master," and William Safire in The New York Times called it "the novel of the year."

Tom Mix and Pancho Villa. The L.A. Herald Examiner said: "A fabulous, big, rawboned wild-blooded adventure tale . . . a novel to make any writer proud and many readers grateful."

The Angel of Zin: a Holocaust Mystery. Publishers Weekly called it "exciting, dynamic, and marvelously written."

Clifford Irving's Autobiography of Howard Hughes. The L.A. Times wrote: "It's almost impossible to know where fact leaves off and fiction begins," and Newsweek named it "The most daring literary caper of all time."

Clifford Irving's Prison Journal. A unique tale of life behind bars and how the author battled for his freedom. The Times of London said: "It has the ring of truth."

To read an interview with Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World curator Chris Jones, click here. >>

This article appears in the June 2014 issue of Sarasota Magazine. Like what you read? Click here to subscribe. >>