Inside the Fascinating, Frenzied World of Art Collecting

More than $31 million for Picasso’s oil painting The Rescue, $28.1 million for Jeff Koons’ 6 ½-foot-high stainless-steel sculpture of Popeye, $22.5 million for Norman Rockwell’s 1957 Red Sox spring-training locker-room work The Rookie. It’s been a very good year for some sellers at auctions run by Sotheby’s and Christie’s in New York.

But for most art collectors, these figures are like the quantum concept that an object can be in two places at one time, or the possibility that our galaxy will collide catastrophically with another in 2 billion years—fascinating, but irrelevant. “You’re probably talking about 500 people in the world” who might purchase a $20 million painting, says Allyn Gallup, proprietor of the art gallery that bears his name on Sarasota’s North Palm Avenue. Actually, estimates of the number who might play in that arena stretch past 1,000, depending on who’s doing the counting, but that’s not exactly a crowd on a planet with almost 7.2 billion inhabitants.

For the vast swatch of serious collectors who are wealthy but somehow didn’t make Forbes’ 2014 global billionaires list, the art that’s attainable is priced in the thousands, or tens of thousands, or, much more rarely, $50,000 to $100,000 or above.

The best of this, while often lovely and sometimes extraordinary, lacks the cachet of, say, a $1 million statuette that could potentially be the object of a torrid bidding war at a nighttime auction in London or Beijing among a Silicon Valley titan, a Wall Street financier, and a Russian oligarch. It usually also lacks the bizarreness that can make the contemporary art world’s priciest corners seem like alcoves of the theater of the absurd.

Your local gallery is unlikely to feature, say, a rotting, formaldehyde-injected, stuffed shark like the one famously “created” by the British artist Damien Hirst in 2008 for the advertising mogul and mega-collector Charles Saatchi, who sold it to New York hedge-fund manager Steven Cohen, reportedly for $12 million. Or a “sculpture”—actually 355 pounds of cellophane-wrapped candies piled up in a triangular pattern—produced by Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres and meant to be consumed by guests of the work’s owner, to signify the brevity of life. (Yes, the candies can be replaced at the sweet shop of your choice.) It fetched $456,000 at Sotheby’s in 2000, well after both its creator and the lover who had inspired the work had died of AIDs. Or an oddity like My Bed, the controversial work by U.K. bad-girl art-establishment provocateur Tracey Emin, one of the two or three most salable female artists in the world. It’s the actual bed in which, after a bout of depression over a romantic breakup, she slept with various companions. Replete with stained, disheveled sheets, booze bottles, cigarette butts and extremely intimate objects, it was purchased by Saatchi from her in 2000 for £150,000 ($252,000 at the recent exchange rate). He plans to sell it in London soon as part of a larger auction of his artworks. Christie’s estimates it will fetch £800,000-£1.2 million.

Some things, however, do connect the worlds of unfathomably expensive, sometimes unfathomable artworks and their much cheaper mainstream counterparts. In both, there’s absolutely no assurance that what is considered good today will be considered good tomorrow, and no assurance of eventually profiting on a purchase if it’s resold. That’s why, in talks with collectors, dealers, and art experts, one theme is repeated: Buy what you like, not what you hope will turn out to be profitable.

Keith Monda, philanthropist and former corporate executive, jokes that he has the “collector’s gene.” As a child, he amassed comic books, toys, marbles and even matchbook covers. Now his focus is on antique toys and modern and contemporary art.

His home overlooking the Gulf of Mexico contains what likely is one of the most stunning private displays of modern and contemporary works in Sarasota, epitomized by a large aluminum sculpture, on a rise between his pool and the beach, by Chattanooga-based John Henry, known in the U.S. and Europe for creating monumental works out of metal. Inside the house, impressive pieces include a series of color-splotched paintings by Bauhaus artist Josef Albers, who emigrated to the U.S. from Nazi Germany, and a 10-foot-by-10 foot painting by the versatile Spaniard Teo González, filled with thousands of individual sea-bluish squares so painstakingly drawn that, at initial glance, it appears to be a textured tapestry. There’s also a tall and striking work by British sculptor Julian Opie, in which a woman’s painted silhouette is sandwiched between two pieces of clear glass. It exerts a siren call on a visitor seeing it for the first time.

Monda, 67, says that when he began collecting art, he thought he knew what he liked, but wasn’t really sure. Now, “after you’ve seen enough to know what you like, you become more confident in your own taste,” he says. “There’s no objective standard; it’s what appeals to you. I like contemporary and modern art. Within that, either the art speaks to me or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, I don’t have any interest.”

But determining precisely what speaks to him wasn’t a snap. Three decades ago, living in Manhattan and immersed in his career—his resumé includes senior management positions at Timberland, J. Crew, Pfizer and Coach, the handbag maker, where he was president before retiring in 2008—he decided to take a few drawing courses, simply to see “how it felt to be on the other side of the equation.”

Monda, a trustee of New College and director of All Faiths Food Bank who, with his wife, Linda, has committed $10 million to his alma mater, Ohio State, for scholarships, adds, “I would buy books, go to a lot of auctions and galleries, just to look at the art and get exposure to all the possibilities. I was trying to develop a point of view. Gallery owners are a great source of education. They tend to be very open. You could ask questions and learn a lot.”

Allyn Gallup, the Palm Avenue gallery owner, certainly agrees with that. Prices at his establishment generally range from $2,000 to $15,000—quite reasonable, given the quality of some of the pieces on display in his 3,000-square-foot shop. Among them: works by Craig Rubadoux, Syd Solomon and Leslie Lerner, all artists connected to Sarasota and having national reputations. The problem is that he has encountered many would-be buyers who have no clue about what they want, but won’t admit it. “People, by and large, don’t have much of an eye; they haven’t decided what they like. Many are intimidated by art, no matter how wealthy they are, so an intermediary is very important. He or she can give the incipient collector that confidence, in the beginning at least, needed to help develop a taste,” Gallup observes. “It’s relatively easy to buy a Mercedes every couple of years, because everybody knows what a Mercedes is. But when one thinks about putting out five figures for a real work of art, as opposed to something merely meant to fill empty wall space, that takes courage and confidence. Many people just can’t do it.”

Another way to start building knowledge is to tap the expertise of an experienced collector. When Nancy Kotler practiced law in Chicago, one of her colleagues had “a very nice collection” of studio glass. He invited her and her husband, Philip—an internationally known marketing expert, author and professor at Northwestern— to his home. “He began to mentor us. That was one factor that got us started,” she recalls.

Studio glass is made in a kiln small enough to fit in an artist’s studio, in contrast to the larger furnaces used in glass factories. In addition, true studio-glass art is one of a kind, not mass-produced. It’s a young genre, dating back only to 1962, when the technology was developed. But it’s one that can produce strikingly beautiful objects, such as those in the 100-piece-plus collection that the Kotlers, who split their time between the Windy City and Longboat Key, eventually plan to donate to the Ringling Museum.

For about seven months through this June, the initial 35 of these works were displayed at the museum. Perhaps the most arresting: a sculpture of a reclining dress, part of a series of such pieces by Karen LaMonte, an American artist who has said she uses clothing as a metaphor for identity. Also impressive: Czech artist Peter Hora’s Juno 11, a yellowish sculpture that brings to mind a happy version of the monolith found on the moon in the original 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Nancy Kotler says that, in addition to visiting galleries, one of the best ways to learn about studio glass is to attend the annual show held each November at Chicago’s Navy Pier by SOFA—the Sculpture Objects Functional Art + Design organization. Dedicated to three-dimensional art, it features lectures on studio glass, as well as exhibitions by various dealers. She also suggests joining the Art Alliance for Contemporary Glass.

Indeed, shows and fairs are excellent places to examine works in person, regardless of what kind of art you’re seeking. Florida has a world-class fair in Art Basel Miami, held each December, but lots of smaller ones pop up locally throughout the year.

The easiest place of all to start doing research? The Internet. Just about every artist has a website, as do dealers, auction houses, art advisers and museums. You can study, buy, sell or merely browse art online at dozens of sites, such as artforum.com, artfacts.net, saatchiart.com, artsy.com, and even amazon.com.

***

What makes art desirable has been debated ever since Paleolithic-period artists began drawing on cave walls. But among the key factors are the work’s perceived quality, rarity, provenance, authenticity, and, of course, the artist’s reputation.

Quality and reputation are intertwined and are the most subjective of these elements. They can wax or wane spectacularly; even Michelangelo has been out of vogue in some periods. Consider Norman Rockwell, whose painting The Rookie was mentioned earlier. For years, “serious” critics scorned him as a mere illustrator, uninspired, unimaginative, unimportant, insipid, sloppily sentimental; many still do. But, obviously, some people disagree, including the anonymous buyer who anted up $46 million at Sotheby’s last December for Saying Grace, a painting of a boy and his grandmother doing just that in a cafeteria, amid much less reverent types. The seller was the family of the former art director of the Saturday Evening Post, which paid Rockwell $3,500 for the painting, for use on the cover of its Thanksgiving 1951 issue. Other Rockwells have fetched once-unthinkable prices, too.

How could a painter so disliked by the art establishment vault into the stratosphere? For one thing, the general public had always admired Rockwell’s work, for its accessibility, humor and the emotions it can evoke. In addition, some famous actors, movie directors, art patrons and even artists were fans. Among them: Andy Warhol, as canny a collector as he was an artist/businessman. (His Silver Car Crash holds the record for a price paid for an American work: $105.4 million.) More important, especially after Rockwell’s death in 1978, his paintings began showing up in exhibitions at renowned museums, such as the Guggenheim in New York and the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

This brings us to the third element of value: provenance. Simply put, if a work has been owned by a major collector or global celebrity, appeared in a top museum, been displayed by a leading dealer, sold at Sotheby’s or Christie’s or a top art fair, or has an intriguing back story (for example, if it once belonged to Marilyn Monroe), it’s worth more than something of identical artistic merit. Connected to this is authenticity; forgers, like rust and political fund-raisers, never sleep, as the Ringling’s recent Intent to Deceive exhibition showed.

The last element—rarity—is less straightforward than it might seem. Nowadays, it not only means that an object is not one of many; it also might mean that it actually has been produced by the artist to whom it’s attributed, rather than by one of the artist’s assistants. Sometimes, the artist’s only connection to a painting is in telling his crew what to do and checking to ensure that it’s done. Lots of works by Warhol, Koons, Hirst and a host of other modern artists fall into this category. Historically, a work by someone from the school of, say, Rembrandt—even one that the master had started and the follower had finished—wasn’t considered anywhere as valuable as something by the artist himself. Those days are gone.

A nice thing about buying something at a local gallery: It almost certainly will have been created by the artist who signed it.

***

The basic economics of the art market are simple and complex, as Don Thompson, an economist at York University in Toronto, has made clear in two perceptive and amusing books that anyone interested in modern and contemporary art should read.

The first is The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, which takes its title from the Damien Hirst work cited toward the top of this article.

The second is the just-published The Supermodel and the Brillo Box. In part, its title is derived from the somewhat ghoulish wax figure by Maurizio Cattellan, a puckish Italian artist, of the head and very impressive torso of Stephanie Seymour (she of Victoria’s Secret fame), hands coyly placed over her naked breasts. Meant to be mounted on a wall like the prize of a successful hunter, it’s called Stephanie, but often referred to as Trophy Wife. Commissioned by Seymour’s husband, investor Peter Brant, in 2003, it drew a winning bid of $2.4 million when it was sold seven years later at Phillips de Pury, a New York firm that, with Bonhams, tops the second tier of auction houses. As for the Brillo box in the book’s title, it’s a Warhol, appropriately named Brillo Soap Pads Box, made of plywood, that garnered $722,500 at Sotheby’s in 2012. And neither Trophy Wife nor the Brillo box actually was made by the artists to whom they’re attributed.

In his books, Thompson argues that art, like toothpaste, cars, or athletic footwear, benefits strongly from branding. “Branding adds personality, distinctiveness and value to a product or service. It also offers risk avoidance and trust,” Thompson writes. In the art world, a branded work is one created by a famed artist, say, Willem de Kooning. Or exhibited in a big-time museum, like the Tate Modern in London—especially in a one-artist show. Or displayed at a topnotch gallery, like the dozen in the U.S., Europe and Asia run by the world’s current No. 1 dealer, Larry Gagosian. Or auctioned at night (daytime sales are less prestigious) at Sotheby’s or Christie’s. Or owned by a world-class collector, such as Steve Wynn, the Las Vegas and Macau gambling magnate who bought Jeff Koons’ Popeye.

It’s more complicated than that, however, Thompson argues, because many more factors than can be listed here come into play. One is the Veblen Effect—as in Thorstein Veblen, coiner of the phrase “conspicuous consumption.” It holds that higher-priced goods always seem more prestigious and desirable, even if they’re no better than, or even inferior to, competing products. Thus, as the bidding goes up, a painting or sculpture can seem more attractive—if someone else is willing to pay that much, it must be good! This, in turn, pushes the bids even higher.

Auctions themselves are rather opaque. Someone who buys a painting directly from an artist or from a gallery pays a set price. The gallery may take 50 percent of whatever’s paid—arrangements can vary between dealers and sellers—but that doesn’t matter to the buyer. At an auction, however, the purchaser pays the hammer price, meaning whatever he’s bid, plus a “buyer’s premium,” atop that. At Christie’s and Sotheby’s, the stated premium is 25 percent on a sale up to $100,000, 20 percent on any portion of that sale above $100,000 and up to $2 million, and 12 percent on any portion above $2 million. The last figure is significant because, combined, the Sotheby’s-Christie’s duopoly is believed to sell 90 percent of all artwork fetching $2 million or more around the globe.

Thus, auction houses’ aim is to reap two paychecks—one from the seller (frequently 10 percent, plus insurance costs) and one from the buyer. Nice idea, even though it could be argued that they’re providing absolutely no service to the buyer and that, if they are, they’ve engaged in a blatant conflict of interest, by representing both sides in a deal. What’s particularly odd about this is how complacently buyers now accept this arrangement, which raised a furor when it was introduced in 1979.

Of course, a very important client can negotiate a discount on the buyer’s premium, just as a seller with clout might be able to persuade the auction house to trim or waive its commission. But the average collector falls into neither category.

Are you likely to make money on art?

In an e-mail interview, Don Thompson says don’t count on it, particularly for works priced at $50,000 or less, because there’s no way of knowing how popular an artist’s work will be down the line. His studies indicate that “half the artists in an important evening auction this week will no longer be offered in the same evening auction 15 years from now. Of the 1,000 artists who had serious gallery shows in New York and London during the 1980s, no more than 20 [had works] offered in evening auctions at Christie’s or Sotheby’s in 2007.” And he adds: “Eight of 10 works purchased directly from an artist, and half the works purchased at auction, will never again resell at their purchase price.”

Of course, there are other considerations. For one, a worthy art object can be given to a museum or other nonprofit organization, to provide a tax break, equal to its current value, for the donor. On the other hand, art is rather illiquid and can be freighted with insurance, transportation and storage costs. In addition, art sellers don’t qualify for the relatively low federal income-tax rate accorded to long-term holders of stocks, bonds, and other assets.

Steve Wilberding, a former investment banker who at one time helped oversee about $150 billion in assets for the government of Saudi Arabia and whose career took him to many locales, including Japan, India, the U.K., Eastern Europe and Latin America, has mixed thoughts about art as an investment.

He points out that art can be a store of value and inflation hedge and that profits certainly can be made on it. “I once sold about 30 pieces of Indian art for over 10 times what I’d paid for 100 pieces. But that was circumstantial. I didn’t buy it with the intention of doing that; it just worked out that way,” he said. But overall, he concludes, “There are better things to invest in.” Wilberding, whose former employers include Merrill Lynch, says that one of his goals in acquiring art is to use it as a portal into the cultures of the countries in which it was made.

The onetime army officer, a board member of the Sarasota Memorial Healthcare Foundation, is married to Teri Hansen, head of the Gulf Coast Community Foundation. Their waterfront home on one of Sarasota’s keys boasts an extremely eclectic array of artworks—Indian, Chinese, Japanese, American colonial (he’s descended from a Dutch family that was among New York’s earliest European settlers), as well as modern and contemporary American—that blend rather harmoniously. Wilberding’s Indian works have been exhibited at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai. One standout: Mogul, a painting by the artist Rameshwar Singh that colorfully depicts the gods’ giving of agriculture to mankind.

Five years ago, Wilberding made an unusual donation to the Ringling Museum: a collection of just under 70 pieces of Turkeman tribal jewelry, which he terms “one of the better collections of its type in the world.” It will go on permanent display there in October 2015, when a new Asian wing is scheduled to open.

Wilberding bought the jewelry, which combines base and precious materials in shapes both religious and secular, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, a major trading stop for Muslims making a pilgrimage to Mecca. It was at the tail end of Russia’s nine-year war in Afghanistan, which ended in 1989. “These really old family heirlooms were coming in over the mountains in old-fashioned pack trains, and people needed money to make the hajj,’’ he recalls. The tribesmen were happy to sell to him because, he says, he didn’t try to negotiate brutally lower prices. “I would knock the sellers’ price down 5 percent or 10 percent, basically giving them full value. So for four years, I saw the best of what was coming out. I recognized it was somewhat sad to be buying the family heirlooms, but at least I was providing money to those people so they could eat.”

Another benefit: “Some of them were using the money to buy Stingers [shoulder-fired missiles] to knock down Russian helicopters. Since the Russians had financed my opposition in South Vietnam, I was very happy to return the favor.”

One factor that makes it difficult to make money at the lower ends of the art market is that the supply of artists is inexhaustible; anytime a discouraged painter drops out of the market, another hopeful steps in. The number of new works continually emerging is enormous, lessening the chances of success for any one artist. But artists at the higher end have already survived the Darwinian winnowing of winners from losers, so their works stand a better chance of staying popular…at least for a while.

Dave Dabbert, who with his wife, Pat, has run the Dabbert Gallery on South Palm Avenue for about a decade, recalls, “In the beginning, we were scrambling to get the best artists for our gallery. But after we were open for six months, we had the reverse problem. We had artists every week, every month, coming in and asking us to show their works. We still get a dozen to two dozen artists every month that call or e-mail and are looking for gallery space.”

Dabbert, whose prices range from $500 to $50,000, represents artists such as Vero Beach’s Barbara Krupp (“One major collector who bought a piece from us compared her work to that of George Inness,” the 19th-century American artist whose landscapes are prized) and Robert Baxter, an artist who lived in Connecticut, New York, and France and whose most intriguing piece at Dabbert’s gallery is St Arnands—a whimsical takeoff on Sarasota’s St. Armands.

One reason Dabbert—and just about every other dealer—is beleaguered by artists seeking display space is that many art galleries have closed. “When we opened on this street 10 years ago, there were 12 galleries on this block; now, there’s four of us left,” he says. That reflects a worldwide trend, as auction houses—historically where people mainly went to buy resold works—press deeper into the new-art market and the private-sale business, and art fairs and online firms take bigger chunks of the action, too.

Virginia Brilliant, the curator of collections at the Ringling Museum, says that great art collections often are built in one of two ways: through a lifetime of careful purchases—a method favored by two of the nation’s greatest collectors, Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston and Henry Clay Frick in New York—or by buying en bloc, meaning purchasing as much as you can afford, as quickly as you can, as John Ringling did in Sarasota.

“Ringling would often go to auctions and buy lots of objects at one go—2,800 antiquities or 300 medieval paintings, sculptures and works of decorative art at one time,” she notes. “The idea was that, by buying so much, you were bound to get something good.”

Of course, there are people who use both strategies. In Sarasota, the most prominent example might be Howard Tibbals, a philanthropist and one of the world’s foremost collectors of circus-related art.

Tibbals, who has donated $10.5 million over the past 15 years to help fund a wing of the Ringling Museum dedicated to circus history, art and research, collects ravenously. The circus museum and its archives house more than 1 million artifacts—posters, handbills, woodcuts, fliers and even entire masonry walls on which circus ads were pasted. The collection includes a 1576 handbill from Augsburg, Germany, featuring a bearded lady and, most famously, the exquisite 44,000-piece “Howard Bros. Circus,” a miniature, very detailed model of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus of the 1930s. (Unlike some Warhol works, this was made by the artist’s own hands; it took Tibbals 18 years to build it.)

At the same time, Tibbals, 77, has been amassing this material carefully and methodically for about 60 years. He knows precisely what he has and what he doesn’t, and says he still has some holes to fill—especially anything connected to Adam Forepaugh, the late 19th-century circus impresario and formidable rival to P.T. Barnum and the Ringlings. Tibbals, whose good ol’ boy demeanor belies a quick and nuanced mind, says there’s one collection of Forepaugh material, from a defunct museum in San Antonio, Texas, that he’d love to buy: “I offered them a half-million for it, but I guess that just baited their cheese. They wouldn’t sell.”

The collector, whose family made a fortune in the flooring business, has trekked all over the U.S. in search of circus memorabilia, and has employed agents to ferret out material here and abroad.

One of his fondest memories: “Once I sent this guy to Massachusetts. We’d heard that the fire department there was moving and that, when they tore the outer wall open in their old building, there was a fantastic amount of circus stuff underneath. We paid $20,000 for that wall. And we got eight posters that don’t exist anywhere else. Nobody else has ever found others like them, before or after.”

Tibbals also loves Buffalo Bill Cody memorabilia. In fact, he claims to have the world’s largest collection, including a sword the famed hunter and showman owned. Fond memory No. 2: “I went out to Cody, Wyo., where the Buffalo Bill museum is, and I asked a guy there: ‘How many Buffalo Bill posters do you have?’ He said 87. I told him he was standing next to the guy who has twice as many.”

So is Tibbals happy with his massive circus-memorabilia collection? “I don’t think you should ever be satisfied if you’re a collector,” he says. Lots of his counterparts would second that.

Top 10 Art Paydays

What are the highest prices ever paid for paintings? According to the online magazine theartwolf.com, here are the top 10, when inflation through Jan. 1 of this year is taken into account. The list includes only confirmed sales.

The Card Players by Paul Cezanne. Sold privately in 2011 for $250 million (inflation-adjusted price: $258.4 million). Buyer: Royal family of Qatar.

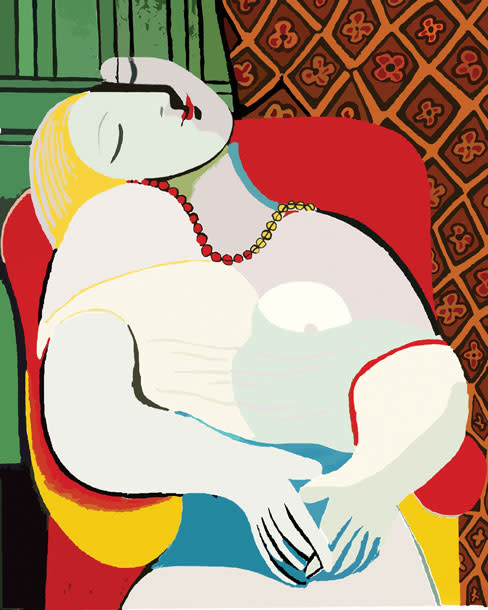

La Rêve by Pablo Picasso. Sold privately in 2013 for $155 million ($155 million). Buyer: Steven Cohen, hedge-fund manager.

Three Studies of Lucian Freud by Francis Bacon. Auctioned by Christie’s in 2013 for $142.4 million ($142.4 million). Buyer: anonymous.

Number 5, 1948 by Jackson Pollock. Sold privately in 2006 for $140 million ($161.4 million). Buyer: anonymous, but widely reported to be David Martinez, a Mexican businessman.

Woman III by Willem de Kooning. Sold privately in 2006 for $137.5 million. ($158.6 million). Buyer: Steven Cohen.

Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt. Sold privately in 2006 for $135 million ($155.7 million). Buyer: Ronald Lauder, cosmetics-company heir.

The Scream by Edvard Munch. Auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2012 for $119.9 million. ($121.3 million) Buyer: anonymous.

Flags by Jasper Johns. Sold privately in 2010 for $110 million ($116.6 million*) Buyer: Steven Cohen.

Nude, Green Leaves and Bus by Pablo Picasso. Auctioned by Christie’s in 2010 for $106.5 million ($112.9 million*). Buyer: anonymous.

Silver Car Crash by Andy Warhol. Auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2013 for $105.4 million ($105.4 million). Buyer: anonymous.

*Sarasota Magazine estimate

Business journalist Rich Rescigno, a former managing editor of Barron’s, lives in Sarasota and wrote “The (Multi)millionaire Next Door” for our March issue.

This article appears in the August 2014 issue of Sarasota Magazine. Click here to subscribe. >>