A History of the Ringling Circus Train

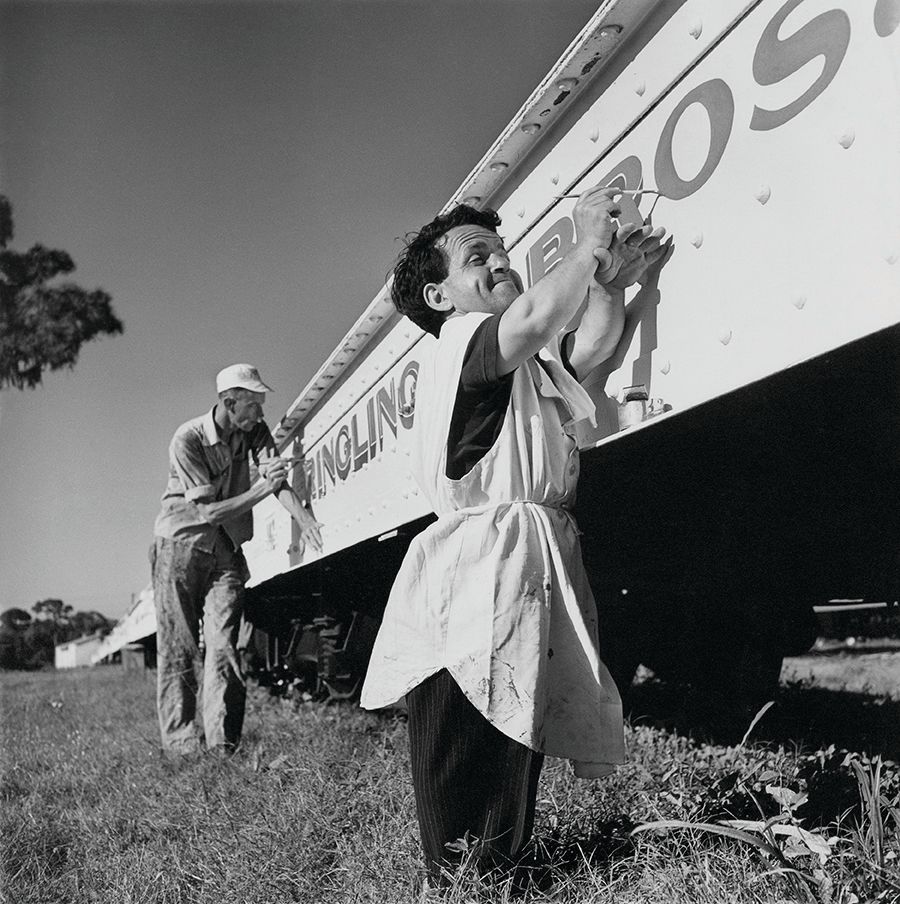

Each year, from 1927 until the early ’90s, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus train could be counted on to bring the greatest show on earth to towns all across America. The caravan was massive, carrying scores of animals, performers, circus staff, and—on one journey, at least—a great photographer. His name was Loomis Dean, a Ringling Bros. press agent, and in the late ’40s, during a long ride aboard the circus train, he shot stunning black-and-white pictures of the Ringling cast and crew. The photos are a vivid reminder of what was most assuredly a one-of-a-kind trip, as is the one-of-a-kind account of it that Dean wrote with Ernie Anderson for Sarasota Magazine in 1992. An edited version of the piece follows.

For most of every year, the 1,600 humans who comprised the cast and crew of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus lived together in the close quarters of a circus train. It was a hard-grinding life. The work was exhausting, as were the large and loud crowds, as was the unceasing music coming from one or another of the circus’s bands. As for the job sites themselves, they were sheltered by canvases that offered scant protection from rainstorms, sleet and high winds. Crises seemed to arise at every moment—wild animals on the rampage, trapeze accidents, lost children, sick elephants, pickpockets, and even, on occasion, deaths.

Every night, we circus folk left the show grounds and made our way, still drenched in adrenaline, to the railroad yards. There was usually an atmosphere of exhilaration—that and a sense of relief that the evening had not ended with someone being killed, maimed or arrested.

We traveled by fourth-class freight, which meant that all regularly scheduled trains took precedence, which meant that no one was ever sure when the circus train would depart. Its hundred cars were broken into four sections, each of which often left an hour or more apart. Still, for many it was home, or a kind of home, anyway.

The privacy was minimal, and the ambiance created by this conglomeration of athletes and beauties and adventurers and freaks and con merchants often resembled a pressure cooker on a slow flame. There were some bizarre happenings, to be sure, most of which occurred in the wee hours in the vast darkness of the railroad yards. Invariably, the yards were surrounded by an assortment of seedy bars and hotels. These were grim and grimy places under the best of circumstances, although they took on a kind of spooky Dante’s Inferno glitter when the circus mob descended into town, pouring into its streets and saloons.

Once the day’s two shows were over, the workers had time on their hands, money in their pockets and uninhibited fun on their minds. The air was electric, and the circus folk attracted a motley assortment of followers in every town where they stopped. There were fantastic things to be seen on those nights, and I saw them all.

The dwarfs commanded the most attention, and not only from the gawkers. Among railroad bar prostitutes—flocks of whom congregated in the railyard and were there to greet the trains on arrival—it was generally assumed that dwarfs, while small of stature, were otherwise enormously endowed, and every now and then I saw a dwarf coax one of these ladies of the evening into a tryst in a nearby phone booth. Later, the girls would emerge ecstatic, praising the dwarfs’ love-making skills.

Author Loomis Dean and Ku Ku the Bird Girl.

Ku Ku the Bird Girl was also popular in the railroad bars. A sideshow attraction, she had a shaved head the size of a grapefruit which she adorned with a single feather. Ku Ku seemed to have a limitless capacity for alcohol. Built Botticelli fashion, with a prominent posterior and tiny legs, she wore enormous bird claws on her feet in the show. After a long day’s work, she loved a good time. It was nothing for Ku Ku to sidle up to some big railroad bar gorilla and ask, “What’s the matter, buddy? Don’t you want to buy a girl a drink?” Then, before he knew it, she’d throw her arms around him for a kiss and scare the poor guy half to death. It was almost surreal.

Love always seemed on the mind of circus folk, although given the cramped quarters, liaisons often took place in lumberyards, warehouses, or even, in extremis, ditches. For all the licentiousness of these scenes, however, I was surprised to discover that the circus had a rigid sexual caste system that made certain relationships taboo.

At the lowest level were the casual laborers, most of whom were winos who joined the show for a few days or weeks and then disappeared into the void. One level up were the workingmen—the roustabouts and the canvasbacks. Then there were the wranglers and grooms who took care of the 1,000 animals on the train. Above them were the sideshow freaks, above them were the propmen and riggers, and above them were the ushers and band members.

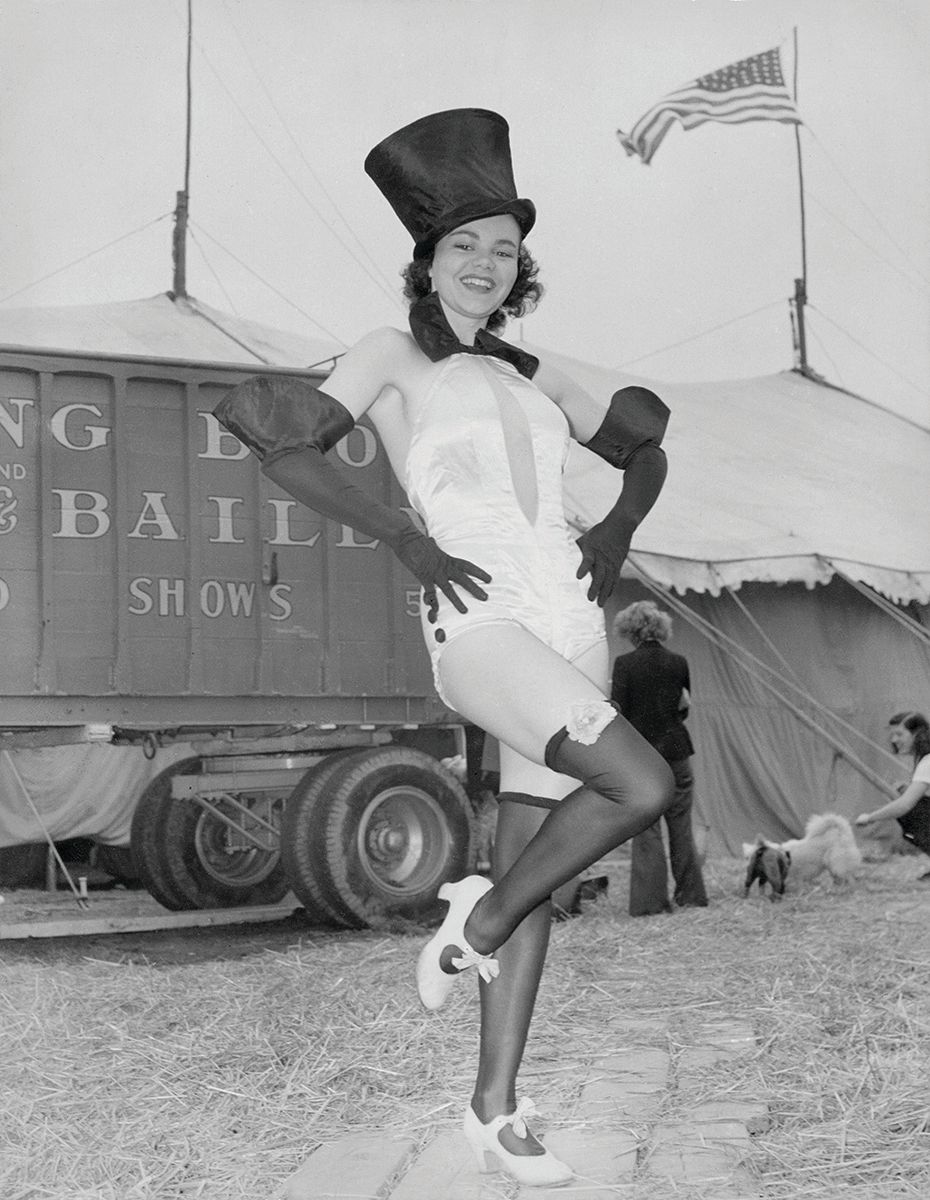

The young showgirls were next up the ladder, and one rung higher still were the monied aristocracy, aka the ticket sellers. The Brahmins were the featured acts, the executives, and of course, the stars.

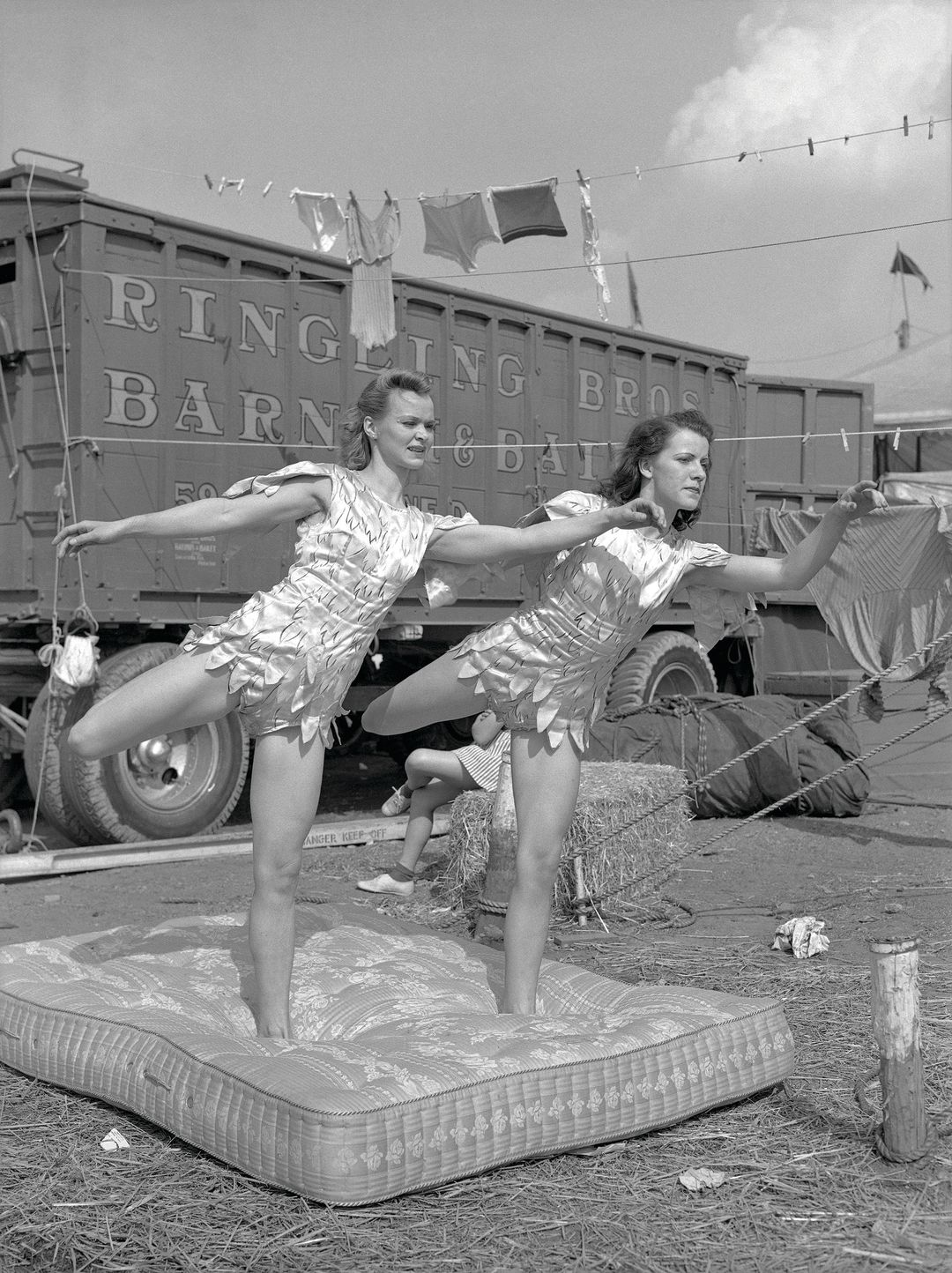

Practicing at the Winter Headquarters in Sarasota.

At every show, no matter the city or town, the loudest applause was always reserved for the California sea lions, who played “My Country ’Tis of Thee” on horns. Accordingly, their trainer, Captain Eddie Firth, always traveled in one of the circus train’s fanciest cars, along with the powerful ticket sellers, who always seemed to be carrying great rolls of cash in their pockets. The sea lions, meanwhile, were always just one car away, traveling in a special tank Firth rigged atop a flatcar. The car always had a freezer full of vast quantities of fish for the sea lions, which Firth always seemed to be defrosting and feeding to his brood. He always washed his hands thoroughly afterward, however, as the meticulous ticket sellers would not tolerate the smell of fish in the fancy car, even if it came from the man who ran the circus’s hottest act.

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey was known as a Sunday-school outfit, meaning that there was never supposed to be any grift among the ticket sellers. Indeed, there was far more of it among hustling ticket buyers, who often pretended to be shortchanged and then raised a beef. In the end, sellers usually paid off the interlopers, just to get rid of the nuisance.

Aside from the sea lions, the circus’s biggest attraction was a young and beautiful European aerial star. She, too, found her way to the railroad bars, usually the best booth in the joint, where she held court like a princess. It was hard to believe she was the same girl I’d seen earlier that evening, way up in lights, her supple body in the briefest costume on the slightest trapeze. She’d swing back and forth on one foot and then stand on her head and keep right on swinging.

Nobody could possibly do that, I thought. I had other thoughts about the aerialist as well, as did every other male in the audience, I imagine.

The circus train carried some 1,600 people, from showgirls to clowns, along with a thousand animals.

Keeping secrets was impossible on the circus train, which is how I heard that the aerialist was steadily but irregularly involved with one of the advance press agents, irregularly because he caught up with her no more than once a week. In consequence, her eyes roamed, and sometimes they found a sharp young ticket seller or ruggedly handsome animal trainer, either of whom might find himself the lucky winner of a post-midnight rendezvous on the train. I myself drifted across her sightlines night after night, dreaming of exchanging my humble berth for an idyll in her stateroom, if only for one magical night. Alas, she never seemed to see me.

In the railyards, there was a constant fear that one or another of the train’s four sections might pull out and leave town.

Missing the train was an unimaginable calamity. If any of the circus folk had gotten into trouble with a town’s authorities, the brotherhood would conspire to spirit them aboard the first section out, no matter their usual berth.

First to leave was always the 25-car contingent known as The Squadron, which traveled a day ahead of the rest of the circus, bringing with them vast amounts of feed for the animals, as well as the sideshow freaks, the “early animals”—the ones that didn’t work in the ring, that is—and candy butchers. A few ticket sellers rode in The Squadron, too. It was their job to send the word out that the circus was coming to town.

My berth in the ushers’ car was in the third section, which also carried 10,000 hardwood reserved seats. When the train was ready to pull out of the yards, you’d hear two whistle blasts about five minutes apart. The train would leave with or without you, so there was always a mad scramble to get on board. In the middle of all the running, sometimes I’d see a big, oversize acrobat grab a dwarf by the seat of his pants, put him under his arm and then chuck him aboard.

The lowest orders of the circus were the laborers. They arrived in the fourth section of the train crammed into cars two-to-a-bunk in tiers three bunks high. Terrible, unimaginable things happened in those cars, everything from fights to killings. In the latter case, the crew would just toss the corpse onto the tracks, where it would likely be run over by a freight train or two before being discovered.

Father Eslander and altar boys from St. Martha's blessed the train every year as it left on tour.

For a young fellow like me, the circus train was never less than exciting, and the places it took me were always fascinating. If the weather was good, I’d watch the world go by from a flatcar, my legs dangling over the side. One day, I was sitting with an old circus hand as we passed some of the most beautiful country in America. It was rich farmland, and I saw a picture-book farmhouse in a grove of trees surrounded by snow-covered peaks. There was a white picket fence all around the place, and also a spic-and-span front porch on which a farmer and his wife sat in rocking chairs, both wearing their Sunday best. It was a pastoral scene of peace and beauty worthy of a master painter.

“Would you look at those gillapins?” said my companion, harshly interrupting my meditations on the idyllic panorama before us. The word was circus slang for imbecilic hayseeds. “They’ve never been anywhere, never seen anything. They’re just stuck out here in the middle of no place.”

I couldn’t help noticing that these words were uttered by a circus hand who lived his life in half a berth with only a spare shirt as baggage. Still, I took the point. Were those prosperous farmers, I wondered, any happier than this nomad?