The Ultimate Spectator's Guide to the World Rowing Championships

On Oct. 1, barring unthinkable upset, the Team U.S.A. women’s eight boat will glide up to the starting dock at Sarasota-Manatee’s Nathan Benderson Park, situating itself perfectly parallel to five intimidating international rivals—New Zealand and Romania, more than likely, as well as “Team GB” from the United Kingdom. These are the largest, most powerful boats in international rowing competition, squaring off for the title of fastest in the world.

Just before the start, all 48 rowers, each one an exceptional athlete—endurance powerlifter, really—sit frozen, coiled like springs, arched over their oars. They’re facing their coxswains in the back of the boats, who are making subtle, last-second adjustments to their positioning. Behind the rowers, more than a mile of water stretches to the horizon, a six-minute-long, lung-burning, backbreaking, 2,000-meter crucible.

As of last year’s Rio Olympics, this boat, the U.S. women’s eight, had won 11 straight world championships, triumphing every year since 2006. Now, for the first time ever, they’re defending that streak on U.S. water, in front of a home crowd. Our crowd.

The final coxswain’s hand comes down, and all teams are ready. One more moment passes, as silent and still as sunrise on the water.

Then the starting light flashes, and the six coxswains shout—their voices amplified—over splash and torrent as 48 tracked seats slide backwards and 48 12-foot oars crank through the water at 50 strokes per minute as the boats blast out of the start.

In short: All hell breaks loose.

Spectators and vendors at a recent rowing event at the park.

On the verge of this month’s 2017 World Rowing Championships, Sarasota-Manatee sits similarly poised. Sept. 23 marks the start of the weeklong event, an annual, international Super Bowl of rowing that’s second only to the Olympics in both size and prestige. This year’s championships will draw more than 1,700 athletes from more than 60 countries, plus 40,000 family and fans, and 2,000 local volunteers. The event will be nationally broadcast on NBC Sports and carried around the globe by a dozen international media outlets.

This is the first time the United States has hosted the World Rowing Championships since 1994, when it was in Indianapolis. After 23 years, the pressure is on.

For the athletes, this event crowns years of preparation. Many of them rowed in last year’s Rio Olympics, and almost all have their sights set on Tokyo 2020. Elite rowers work out two or three times a day, six days a week, putting their hearts into 6 a.m. on-the-water training, diets, weightlifting, running, indoor erg races (on rowing machines) and the endless pursuit of the perfect stroke.

Likewise, the 2017 World Rowing Championships organizers, a dozen internationally experienced events experts contracted under Suncoast Aquatic Nature Center Associates (SANCA, the nonprofit that oversees Nathan Benderson Park), have spent the last five years sorting through intricate logistics such as multi-country visa wrangling, equipment shipping, park layout, weather contingencies, vendor coordination, community outreach and volunteer recruitment—not to mention the creation of an onsite, spectator-driven expo offering food, shopping, entertainment and creative, interactive local promotions that will bring the community into the park and send these international visitors out into the community. It’s to be a grand celebration of the sport, the host country—and Sarasota-Manatee.

The payoff for all that prep work, for both athlete and venue, will be a performance that comes across as both impressive and effortless.

But for spectators, the job is easy: Grab a flag and a cowbell and head to the water’s edge. Whether you’re a crew super-fan or a landlubber newbie, from here or abroad, this is going to be a once-in-a-lifetime Southwest Florida experience.

The new, state-of-the-art finish tower at Nathan Benderson Park.

Image: Fawley Bryant Architecture

“I can’t even begin to say how excited I am about this,” says Jenn Weaver, a former collegiate rower, as she steps up to the lake on her first visit to Nathan Benderson Park. She has driven down from Tampa for June’s Youth National Championships, a regatta for high schoolers that also served as the park’s dress rehearsal for the 2017 World Rowing Championships. For rowing fans like Weaver, who spent their careers lugging boats to backwoods courses, wind-swept lakes or tree-choked canals with little fanfare, Nathan Benderson Park is heaven.

There’s a reason this will be the first U.S. venue to host the World Rowing Championships in more than two decades. In fact, there are a lot of reasons.

Weaver carries her 8-month- old son, Zachary, down the white sand beach that runs along the final 350 meters of the course. That’s more than three football fields of open viewing area, one of the world’s most spacious and indulgent settings for watching a rowing race, and close enough to see the competitors’ gritted teeth. Fans clad in team colors, toes in the sand, cheer their boats to the finish, aware that the athletes, just a few meters away, can hear their shouted support. Behind the beachgoers, across a paved path, others watch from shaded grandstands adjacent to a brand-new, six-story finish tower that houses VIP and media areas, as well as an air-conditioned medical headquarters. Two jumbotrons display races up close and in progress, slender boats on the screen darting like arrows.

“Rowing is an incredible sport, but you need to be near it to appreciate it,” says Weaver. “When you have to watch it from a mile away, you underestimate the work and the effort, and also the ultimate beauty of a boat with perfect rhythm. Most [venues] just can’t give you that access.”

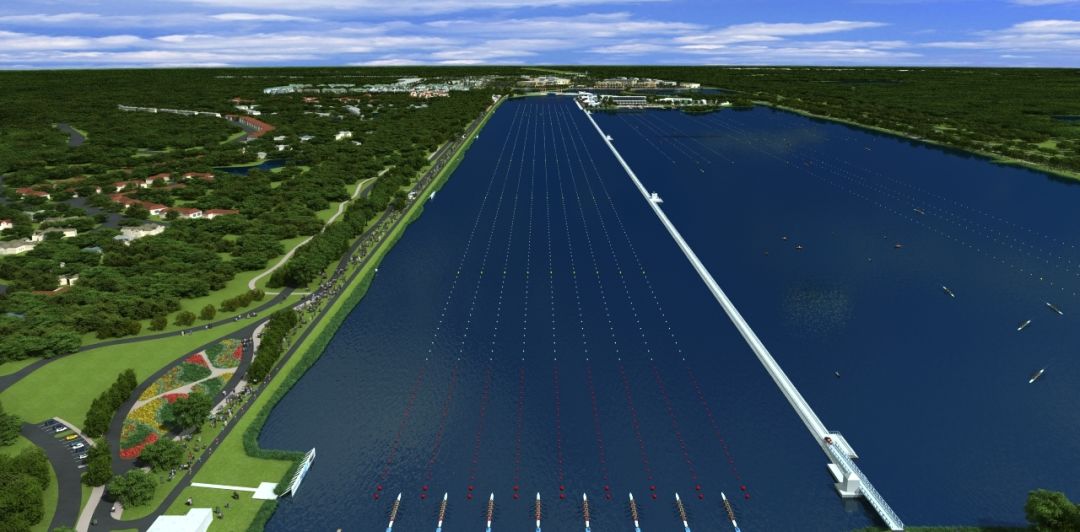

To the left, the vast, rectangular expanse of the race course, like a swimming pool for creatures much larger than humans, stretches back to the starting line.

When Weaver rowed for Stetson University 15 years ago, the courses weren’t always wide enough for six boats and required a tricky turnaround after the finish, with little room to get back to the launch. “If another race was coming down, we had to pull our boats off to the side to let them through,” she says.

Sarasota attorney David Wyant rowed with Sarasota Scullers in high school, starting in the late 1990s, when the only local regatta took place on the Intracoastal between the two Siesta Key bridges. “That’s not a straight line, and it doesn’t support six boats across,” he says.

Wyant now serves as the primary announcer for the Nathan Benderson Park; his is the voice ringing out across the spectator area, calling play-by-play as the boats make their way down the water. “There’s no course in America that’s set up better for a 2,000-meter race,” he says.

From Weaver’s arms, little Zachary eyes a pack of colorful boats, long oars like insect legs, as they glide across the finish and continue forward, veering to the right and then disappearing behind the finish tower. They pass under two bridges and through a narrow canal that opens to the eastern portion of the lake, running parallel to I-75, where teams utilize multiple launching docks and row up and down warmup and cooldown lanes. The ingenious traffic pattern helps to coordinate several hundred athletes while staging a six-boat race every 10 minutes. Weaver marvels, “It’s set up to run like clockwork.”

Because of that little outlet canal, the beach and spectator areas, finish tower, food trucks, vendors, entertainment and team tents—indeed, the very heart of the park—all exist on an island. The all-in-one-spot festival atmosphere is built into the setup.

At the youth nationals event, Weaver overhears a group of boys complain that they’ve qualified for only a meaningless consolation race. “Why do we have to row if we didn’t make the finals?” one asks. Their coach responds, “You have a chance to race in a state-of-the-art facility that the World Rowing Championships is going to be at. Now you can say, ‘I raced at Nathan Benderson Park.’”

Weaver and Zach stroll away from the beach to explore the food trucks and souvenir stalls. At the world championships, the center of the island will be awash in “Fan Fest,” a carnival of American staples served up by local purveyors, including Bradenton’s South Philly Cheesesteak and Sarasota’s Amish Baking Company, along with a beer garden and vendors hawking a rainbow of rowing wares that include—naturally—Venice-manufactured 2017 World Rowing Championships-branded Tervis tumblers.

Here, too, daily themed expos will offer interactive demonstrations and local entertainment—Circus Arts Conservatory performers, a China Smith boxing exhibition—plus live music at the conclusion of each day’s races. Promotions and exhibits will encourage visitors to experience more of Southwest Florida every evening, sending flocks of rowing fans to St. Armands Circle, downtown Sarasota, Bradenton Riverwalk and even local breweries.

At the south end of the island, starting where the beach ends, a wave attenuator, like a broad, low-slung pier, divides the two sections of lake. The steep shoreline and surrounding trees help shelter this venue from wind—“Most of the courses you’ll see, even for national championships, aren’t as sheltered as this one,” says Wyant—but the wave attenuator adds an extra level of calm. In rowing, tranquility is more than cosmetic; it’s key to fair competition. Choppy waters slow boats and disturb the careful choreography of the rowers’ strokes. “A crosswind can ruin your day,” says Weaver.

At the far side of the course, away from spectators, a paved path traces the entire span of the water’s edge. Most days, it’s a waterside trail for walkers and rollerbladers. But during regattas, as boats crank their way down the course, packs of bicycle-mounted coaches keep pace along the narrow roadway, shouting encouragement and instructions. Among rowers, this is known as the “coaches’ peloton.” Crashes are not uncommon.

As Zachary starts to cry, Weaver calls him a “future coxswain,” referring to the position in rowing reserved for a smaller athlete who shouts instructions to the rest of the boat. “I have been out of the water for a long time, but this brings me right back,” she says. “It’s always fun to watch world-class athletes compete. But watching them in a world-class facility will make it just that much better. Fun, awe-inspiring, magical—whatever. It’s going to be awesome. And I can’t wait.”

Despite some unforeseen rain delays, which were handled across the board without incident, organizers declared the youth nationals a resounding success—a good indicator of the readiness of venue and staff. SANCA chief medical officer Dr. Valli Gambina, who oversees a team of first responders at every NBP event, recalls that as the event wrapped up, park officials asked each other, “Do you see how the park came to life? Do you see how it’s running itself? The park knows what it’s doing.”

Emily Regan, left, celebrates with her winning Team U.S.A. at last year's Rio Olympics.

Image: Courtesy U.S. Rowing

Meanwhile, in Princeton, New Jersey, the world-class athletes of Team U.S.A. have been putting in work, too.

Emily Regan was 8 years old when the U.S. women’s eight failed to medal in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, the last time world champions were crowned on U.S. waters. That year, Romania took the title.

But things have changed over the past two decades. Last summer, Regan helped the U.S. women’s eight row to gold in Rio, earning that 11th consecutive world title. That’s a full-blown international athletic dynasty coming to town. Here, Regan and her boatmates will finally have a home crowd behind them, urging their streak to an even dozen.

For the men and women of Team U.S.A., days start on the water: two-hour workouts in single or double boats, followed by rest, then sometimes weightlifting, then another on-the-water training session in the afternoon, six days a week. Rest and recovery are vital.

At 6 feet, 2 inches, Regan has a long, idyllic rowing stroke, the blade of the oar cranking through the water as her frame unfurls. The power starts in the legs and carries through the whole body. The motion can be related to a powerlifter’s snatch, a fluid burst of energy, the synchronized convergence of limbs and torso, repeated again and again, every other second.

“A lot of elite rowers are people you’d consider perfectionists,” says Regan. “You’re doing the same motion over and over and over again, every stroke of practice. You’re always trying to improve it, and it’s never quite what you want it to be. You’ll see a lot of Type A personalities in rowing.”

As the boat moves down the course, the athletes fight two kinds of fatigue, aerobic and anaerobic—respiration as well as muscle. “It actually starts hurting very early in the race,” says Regan. “Your legs are telling you to stop, your brain is telling you to stop, but you have to push through that. We always like to say, ‘Everybody is hurting, and it’s whoever is able to push through that pain the best, that’s who’s going to come out on top.’”

Trailing by half a second halfway through the finals race in Rio, the U.S. boat’s winning margin was just over two seconds. Whatever happens here at NBP, it’s probably going to be close.

Image: iStock.com

“Will there be alligators?”

Meanwhile, in London and Berlin, Auckland and Johannesburg, in training facilities around the globe, international rowers and their fans have a lot of questions about Florida. (“For the most part, alligators stay well away from what we’re doing,” SANCA president Robert Sullivan reassures them. “We have an active [alligator] mitigation program. But for the most part, we don’t see them at all.”)

As they arrive, foreign visitors will realize they’re not stationed in a remote area, as rowing facilities often are, but smack-dab in the middle of bustling University Town Center and its surrounding plethora of shopping and restaurants. After a workout or a race, they’ll be able to snag an Auntie Anne’s pretzel and a new Anthropologie tee on the way back to their hotel, where local volunteers will be stationed to help in whatever ways they can.

At the park’s Fan Fest, visitors from Brussels and Sydney will eat local treats. Brits, Kiwis, Germans and Romanians will watch Sarasota circus performers and learn about Mote Marine and South Florida Museum and area beaches.

It will be an ebullient, international crowd soaking up the very best of Southwest Florida.

And as at any great athletic event—and any great party—you never know what’s going to happen. The fun is in hanging out and watching it unfold. A chance to be a part of something incredible, standing in the crowd at the water’s edge.

Watch for the Irish: Brothers Gary and Paul O’Donovan will try to top their hit performance in Rio, where they won silver in double-sculls—Ireland’s first ever rowing medal—and then gave a series of charming interviews in irresistible accents, which earned them worldwide fandom overnight. (Seriously, google them. They’re delightful.)

Watch for the Netherlands: Dutch fans like to congratulate their winning boats up close, splashing into the water with knee-high exuberance, doggie-paddling out to the athletes, who jump in, too, to greet their fans.

Watch for the underdogs: Athletes from Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Azerbaijan and Benin will be racing to establish their countries’ up-and-coming rowing pedigrees. International support for exceptional talent is a longstanding rowing trope.

And, of course, watch for Team U.S.A.: That 11-year women’s eight world-championship winning streak is on the line. And every single American athlete at Nathan Benderson Park this month will be competing for a world championship on home water for the very first time. They’ll be listening for you.

“That’s one thing the fans should know,” says Bryan Volpenhein, a senior coach for Team U.S.A. “The louder you cheer, the faster we go.”