'My Summer With Irma'

Last month, we learned that Broadway theaters will remain dark until at least January. Here on Florida’s Cultural Coast, Sarasota’s renowned arts organizations are facing a similarly uncertain fate.

An empty theater is a hard thing to get my head around. Thanks to my parents, longtime Asolo Rep artists Brad and Marian Wallace, the theater has always been a living, breathing thing; the interconnectedness of people—actors, audience, artists and crew—is at its heart.

We don’t know when we’ll again be able to gather together to see a show, but in the meantime, here’s a particularly joyful Asolo Rep memory of mine.

In the summer of 1990, when I was 10, the Asolo did a production of a camp comedy called The Mystery of Irma Vep, a famously raucous romp of a “mystery” set primarily in an old English manor house, in which two actors play a dozen or so characters. My dad co-starred alongside another longtime Asoloite, the late Eric Tavares. My mother stage managed.

One of Dad’s main characters was Jane, a maid who spoke (according to his interpretation) in British falsetto, sort of like a cockney Julia Child.

Early in the show, Jane goes off on a little monologue about her former master, Miss Irma Vep, and how Miss Irma had a pet wolf named Victor. Jane’s telling her current master, Lady Enid (Eric, in a wig and fuchsia ballgown), that the children of the household used to ride around on Victor, which the wolf didn’t like but tolerated because he was so devoted to Miss Irma.

You see, Jane goes on, Victor preferred relaxing with his master. “His ’appiest hours were spent stretched out at Miss Irma’s feet,” Jane would say, in Dad’s sing-song, H-dropping, East-London-by-way-of-Alabama delivery, “his huuuge purple tongue lolling out of ’is mouth.”

This is the nonsense that pops into my head when I see dogs with their tongues out: “His huuuge purple tongue lolling out of ’is mouth.”

It was a fun show, even—or perhaps especially—for an awkward pre-teen, bawdiness notwithstanding. A real hold-on-tight comedy bull ride that used every ounce of its gimmick with no room for neuroses. Everyone got tossed around a bit, in an exuberant way.

Early in the play, after another chat between Jane and Lady Enid, Jane would exit stage left, leaving Enid alone on stage for what seemed like the briefest of moments. Eric had just one line in that moment—a quick rebuke of Miss Irma’s scowling portrait—when from stage right, the tweed-clad Lord Edgar (also Dad) barged in through the manor’s front door with a full-size, taxidermied wolf under his arm: “ROUGH WEATHER!”

Without fail, the audience roared. It’s a joyous gag—not just the stuffed wolf and the sudden entrance, of course, but the sheer hysterical, manic magic of it. A heavy-set, big-bosomed, dark-haired woman in a maid’s outfit had just left the stage, as, it seemed simultaneously, the same person entered from the other side as a posh, bald man in a suit.

Eric greeted him with a kiss.

Dad and Eric kept up this frenzied chemistry throughout the show, a dozen different characters between them, telling a preposterous story that travels from the English countryside to Egypt and back again, with physical comedy and prop gags and Vaudeville jokes and mummies and werewolves and vampires and heaps upon heaps of silly voices.

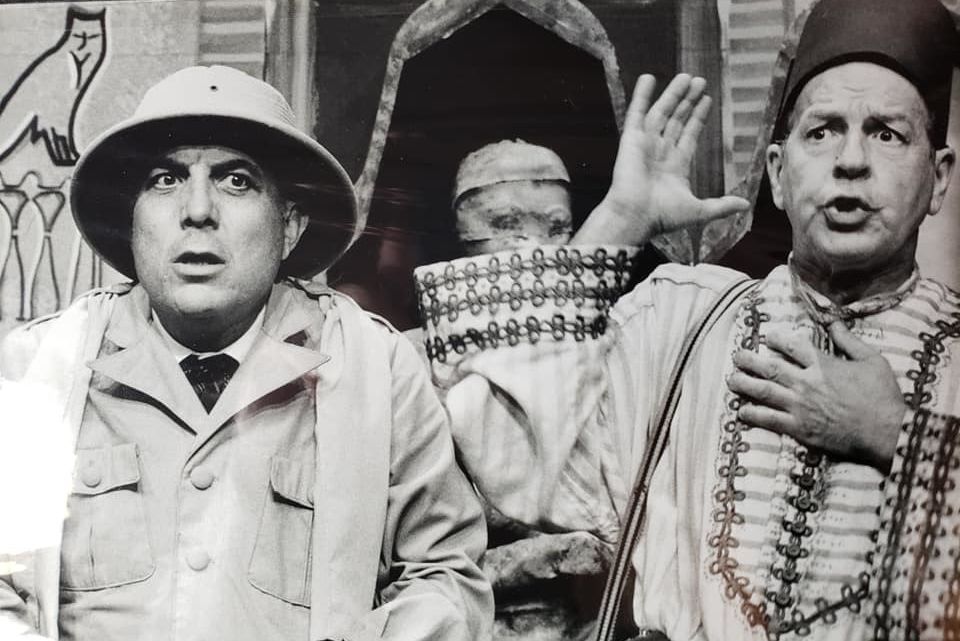

Eric Tavares, left, and Brad Wallace, right, in Irma Vep

Image: Courtesy Photo

With both parents involved in the production, I’d been, as usual, a mindful bystander as the process unfolded. From line memorization and script prep through rehearsals and tech, I’d watched professional adults assembling the meticulous, almost mathematical architecture of broad comedy. But nothing matched the stomach-twisting joy of the performance itself—those months of effort dissolved into what seemed like instant easiness, and all of that energy multiplied exponentially in the guffaws of the audience. What fun, when something so ludicrous can be transcendent.

After seeing it from the house, I rushed to ask Mom if I could sit backstage for a performance. It wasn’t too far-fetched a request; I’d enjoyed a childhood of backstage wanderings and knew well to follow the rules (No. 1: Don’t touch the props). Still, I’d guessed that this was a different beast.

The whole thing already felt like a family affair: Mom and Dad and Eric, of course, but also the backstage crew, helmed by head wardrober Hilare Petlock, a British expat whose whole family was close with ours, and stagehand Darrell Steele, a bearded, impish 20something who’d often babysat my sisters and me. At least, I argued to Mom, I wouldn’t be imposing on total strangers.

Mom relented, but put me on a short leash. The backstage process for this show was delicate and chaotic and, it seemed from her concerns, the mere presence of one little fifth-grader could easily derail the whole thing.

Her cautiousness enthralled me even more.

She brought me along on the next matinee and set a chair backstage left, a full 20 feet away from the costume racks and wig tables. That was my spot, and I was to stay in it, because she couldn’t stay there to supervise me. As soon as she called places from her booth way back behind the mezzanine, I was to sit in that chair and stay put, hands and arms inside the ride at all times. Silence, of course, was a given.

In the darkness behind the set, just beyond the audience’s view, sat an arsenal of costumes, wigs, hats and props. Hilare and the three other wardrobe women, clad in black and armed with tiny maglites, performed distinct roles for every costume change. The moment between Dad’s and Eric’s every exit and entrance was, offstage, a three-second whirl of choreographed actor-decking.

But from my vantage back by the rigging, it might as well have been a rugby scrum. The chair was not shaping up to be the immersive backstage experience I’d hoped for. Not yet, anyway.

Fortunately, it was summer and I was 10 and both of my parents were at the theater six days a week anyway. Since I hadn’t screwed anything up the first time, Ma didn’t put up too much fuss when I again asked to sit backstage for another performance. And again. And so forth. It became a given that after dinner (and for matinees as well), I would accompany Mom and Dad to the theater and take my spot in that chair. A straight run is catnip for an obsessive little brain. It was easy to go all-in.

As one of the costumers later told it, show by show, that chair came closer and closer to the action. As I remember it, I was very much invited; in fact, I’m sure the wardrobe team insisted I join them—a point I later made clear to my mother. (I was still convinced my mere presence could knock the show’s clockwork akimbo.)

Soon enough, there I sat, arms-length from the ladies as they worked, whirling.

The quick-changes relied on precision choreography as well as clever costuming. Both actors wore a base layer of long-sleeve dress shirt, vest, tie, trousers and simple black shoes. To become a be-suited male character, all they had to do was throw on a jacket. And possibly, sometimes, a pith helmet.

The women’s dresses, which appeared complex and luxurious, were in fact all one big piece—heavy beanbag boobs and everything—that velcroed in the back. To become their primary female characters, Dad or Eric would toss off their previous trimmings and dive arms-first into the big dress-frock that was being held up by one of the costumers, as another wardrobe assistant sealed the Velcro and yet another topped them with the appropriate wig, perhaps exchanging a feather duster for a meat cleaver in the process.

Then, just to make it extra impressive, the actor often dashed off behind the crossover to make a mind-blowing entrance from the other side.

Performance after performance, I kept coming back to my chair, clad in my own kid-size all-black T-shirt, jeans and shoes. This is where Hilare once explained to me that sometimes black dyes were made from a red base, which is why the crew’s black outfits sometimes glowed red in the dim, blue backstage light. Irma Vep is what I think of, even now, when I see black clothing in the dark.

Once I was always over their shoulders, the costume ladies found a fun game in coaxing me out of the chair and coaching me into the roles that were becoming so well worn to them. I had the small sense of being a novelty—a little kid being played with—but participating in the process was irresistibly fun.

They handed me Jane’s heavy maid’s getup, stood me in the proper spot and made sure I presented the costume just so, arms held high, the open back facing away from me, sleeves open and clear.

In a moment, my dad raced offstage, threw off his tweed jacket, and there I was, eyes peering over the frill. He dove his arms into the sleeves, donned his wig, and in a flash was off again. I was left terrified and thrilled, like I’d high-fived a jockey mid-race. No crises, no stumbles. The show stampeded easily on. I picked up the discarded tweed jacket and hung it in its spot.

The team arranged such adventures for me again and again—a gown here, a fez there—and then back to my chair.

These intermittent, three-second, chaotic costume changes constituted only a portion of the time spent backstage. While both actors were onstage performing, the backstage team busied themselves cleaning up the quick-change carnage, readying their stations, and then sitting poised, waiting.

Well, not always. Not quite.

As the run progressed, the whole cast and crew, as happens, went a little mad.

Onstage, Dad and Eric stayed in character for the audience but found moments to catch our eyes, too, and make faces at us. Backstage, the grown women in my midst responded by putting flashlights up their noses.

During one long lull in the show, I’d been sitting obediently in my chair, though the rest of the costumers had wandered off. After a few quiet moments I saw the women returning in a pack behind the crossover, stifling giggles and…buttoning their shirts?

Looking across to the other wing, I saw Darrell, eyes closed, rolling on his back, holding his stomach and kicking his legs in the air in a silent laughing fit.

“What did you do?!” I whispered.

Hilare whispered back, “We flashed him.”

Wallace in costume in Irma Vep

Image: Courtesy Photo

And so it went. An absurd, blissful routine seen through elementary school eyes. Charlie Bucket Goes Backstage.

Then one afternoon, trailing my parents, I arrived in the green room to learn that one of the costumers had injured her wrist—not terribly, but enough to hamper her in her duties. And there I was, literally waiting in the wings, a fully prepped, miniature understudy.

At some point in a child’s self-conscious precociousness, inching toward validity, you hit the Uncanny Valley of adulthood: You’re just grown up enough to know that you’re very much not one of the grownups; and you know full well that all of the grownups know this, and no matter what, you’ll never really join them until you’re older. And by then, all of this will be something else entirely.

But boy did they let me play at it anyway.

I slid into the role of wardrober No. 3, by now comfortable with what changes happened when and where; which Styrofoam head held Jane’s wig and which was for Lady Enid’s; when to bust out Eric’s caftan and where to put it when they were done. I could stand confidently on set but behind the curtain during the Egypt sequence, watching Darrell swap out the fresh mummy mannequin for its decrepit counterpart.

The injured costumer, still a lovely supporting angel, stayed and supervised. The chair was all hers.

Every performance ended in triumph for the team. Rightly so, the wardrobers had been included in the curtain-call staging from the get-go. After Dad and Eric took their bows, the two men turned and gestured toward upstage center, where the four women in black appeared, arms overflowing with costumes, to cheers from the audience.

I don’t know quite when in the run it happened, but I still carry this crystal-clear image in my head of the pack of them, heaped with dresses and coats and wigs and shawls, just moments before walking onstage to take their bows. In that moment, they’re turning back, facing into the wings to where I sat, and waving at me, once again, to join them.

I hesitated. More than anything else, this would seem my most egregious violation of the “sit in the chair and don’t bother anyone” command. Plus, I could pretend to be a grownup in the dark, but in full view of the audience I figured I was still just a kid being humored. I was afraid of breaking the spell.

But with a few shows’ coaxing, they got me out there anyway. Holding my own load of livery, standing onstage with the team, looking past my Dad and out over the 400 strangers, awash in applause. Still spellbound.

My poor mom. She’d left me in the chair, safely out of the way, and gone off to do her job. And next thing she knows, moments before the curtain falls, she looks up to see her 10-year-old literally in the show.

You’d think that was the moment. You’d think that was the very best bit. But then you would’ve missed the point of the story: that all the best bits happen behind the scenes.

Another matinee, another routine arrival in the green room. This time, the four women greeted me with a tiny present in green paper. I unwrapped it to find my own little backstage maglite, just like the rest of the ladies in black had: dark blue casing, adjustable beam in a nostril-sized lamp—perfect for finding wayward wigs or taunting unruly actors.

I gushed my thank-yous, slipped it in my pocket, and went on to take my spot in the dark.