Go See the New Film Path of the Panther

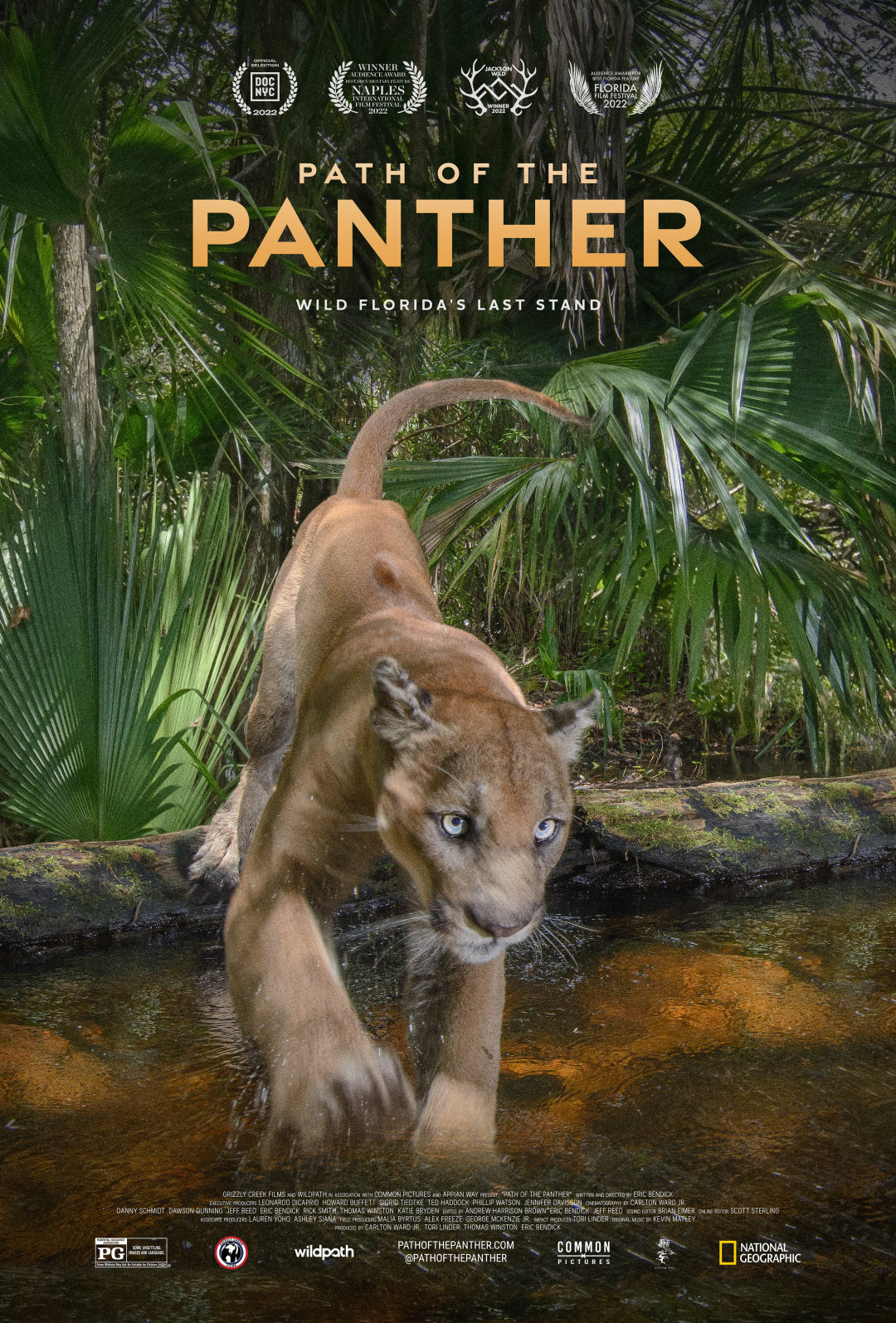

Image: Carlton Ward Jr.

To see a Florida panther in the wild is a miracle. Most people will go their whole lives without ever seeing one—even the ones who look real hard. Panthers are like ghosts in the swamp—and they are also few in number. Just over 200 Florida panthers remain in the wild, and as the state swells with newcomers and new developments, the likelihood of catching a glimpse of the animal shrinks even more.

But the new documentary film, Path of the Panther, allows us to see the elusive cat in all its secret glory like never before.

The film follows wildlife photographer Carlton Ward, Jr. through the wild heart of southern Florida as he tries to capture an image of the first female Florida panther to make it north of the Caloosahatchee River in 43 years. Ward, who always has a camera and machete in hand as he slogs his way through pristine Florida swamp, set up cameras with infrared trip sensors, which make up much of the film’s footage.

The importance of capturing this image is providing concrete proof that the panther’s range is expanding, furthering the need of the Florida Wildlife Corridor. The Florida Wildlife Corridor is a nearly contiguous 18 million square miles of wild land through the heart of the state. So far, 9.6 million acres are protected, but another 8.1 million acres do not have conservation status and risk being turned into developments.

Even though Ward grew up on a ranch in southern Florida, it took him four decades to see his first panther. “I’m pretty sure I heard the cry of a panther in the woods on my family’s ranch when I was a kid,” Ward says. "But the first time I definitely saw one was in 2017, when I was running camera traps at the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge. I looked up and saw one gliding between the cypress trees like it was walking on water.”

Ward, like so many other sons of Florida, left the state for a while and spent time traveling abroad, photographing the rainforests of Gabon and the elephants of Mali. Each time he returned to Florida, it was a changed land. In the film, Ward says he thought the Florida he grew up in would be around forever. And Florida does look like forever in Path of the Panther. Through Ward’s camera, the untouched parts of our state look biblically old, like Adam and Eve might pop out of the bushes.

He hopes the film, which took six years to make, will have an effect on its viewers. “I want everyone who sees it to have tremendous pride in the state of Florida and know about the Florida Wildlife Corridor and the importance for its future,” Ward says. “That’s why our team spent so many years focusing on the Florida panther. It’s a symbol of the need for protecting the corridor.”

The panther is a symbol of modern Florida. It used to be that panthers roamed the whole of the continental United States. Now, these Florida panthers are the last of the big cats east of the Mississippi. We forced them to the tip of southern Florida, where the land is drowned and harsh. But now we want that land, too.

The panther isn’t the only thing that is in danger of disappearing. “I guess you could say the Florida cowboy is an endangered species, too,” Elton Langford says in the film. Langford, a DeSoto County commissioner and rancher, is used in the film to show how the future of the Florida panther and the Florida rancher are tied together. Florida ranches make up much of the Florida Wildlife Corridor and provide necessary habitat for the panther.

In the film, there is hope and tragedy. One scene is particularly heart-wrenching. Ward stumbles upon a female panther waiting for its cub. When the young cub arrives, it struggles to walk. It was stricken with a rare feline neurological disorder, which is exacerbated by the panther’s lack of genetic diversity.

The hope is found in victories both big and small. A young male is struck twice by vehicles—car collisions are the No. 1 killer of Florida panthers—and has three of his legs broken, but against all odds, he makes it back into the wild. There are legislative victories as well. A toll road that would cut through panther territory is halted, and 17,000 acres are turned into conservation easement along the wildlife corridor.

My favorite part of the film is when Ward sets up his cameras and moves and acts like a panther would to make sure the shot is just right. In these scenes, Ward embodies the animal like some kind of shaman performing an ancient ritual.

Go see the film at your local theater and get to know the state you live in.