With Parade, Shinique Smith Turns Her Gaze on the Ringling's Old Masters

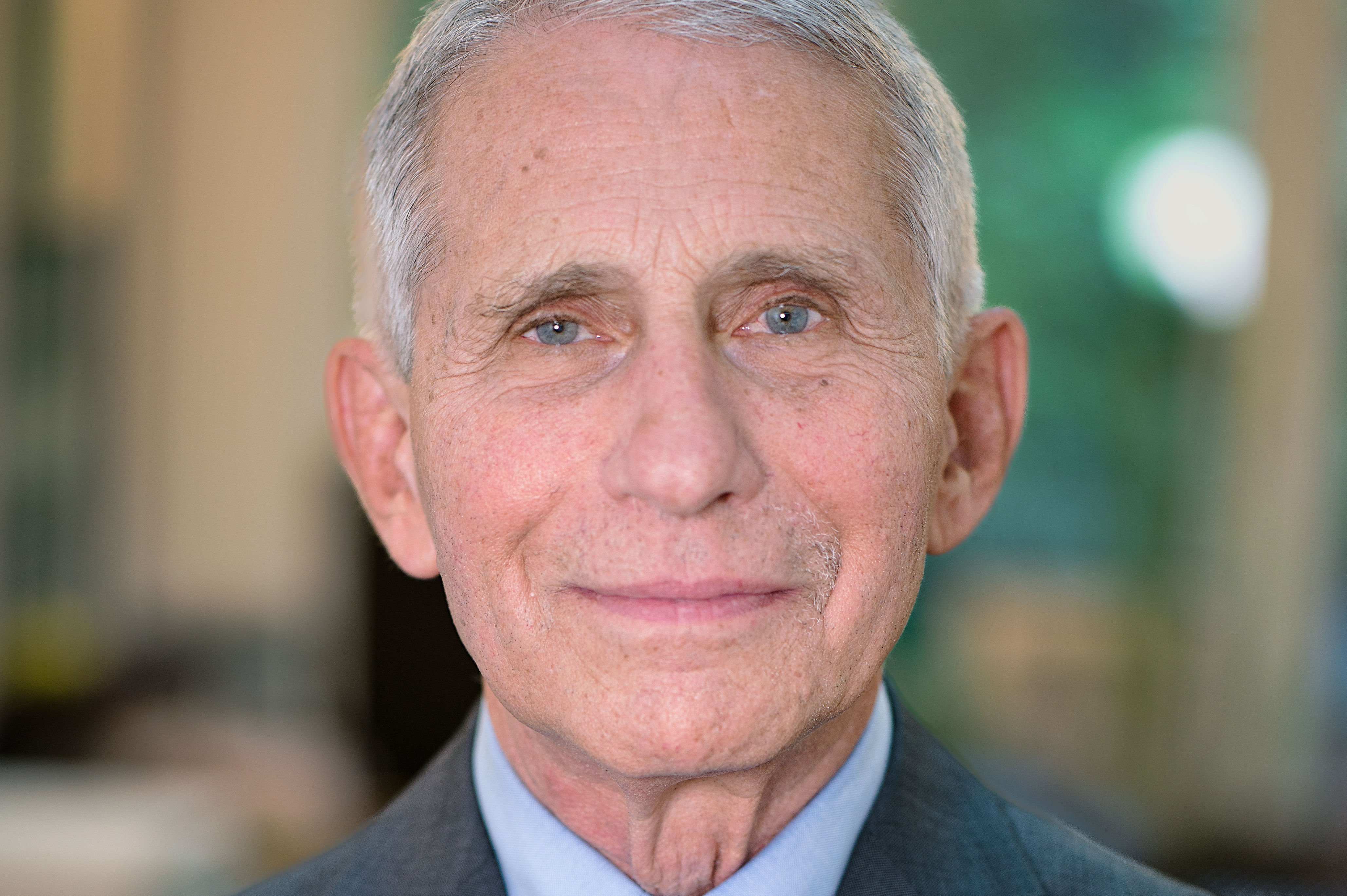

Shinique Smith at the opening reception for her show Parade at The Ringling.

Image: Courtesy Photo

It's no secret that many of the works at The Ringling were painted by white men. The galleries are filled with classic art by European Old Masters ranging from Rubens—whose five large-scale paintings from Triumph of the Eucharist greet visitors when they enter the museum—to Gainsborough, Tiepolo, Velázquez and Veronese.

Now, with her show Parade, Los Angeles artist Shinique Smith is inviting viewers to engage in a dialogue about those Old Masters, posing questions about classical and contemporary art, size and scale, and gender and ethnicity. The show, which opened in December, is on display until January 2025.

Image: Courtesy Photo

Smith is known for her large-scale sculptures, which she calls "bales" and which are made from clothing and other textiles like ribbon and rope, as well as family heirlooms like jewelry and even furniture. Those are on display in Parade, as are some of Smith's smaller pieces—all of which, she says, have "a whole universe" inside them.

"My view of the world definitely goes into the work," Smith says. "I often go from the micro to the macro in my thinking and in the way I view things, and I work that way, too. I create small and big, from small drawings or collages to [pieces that are] 150 feet. But I treat them the same way compositionally. I want the viewer to be able to step in [to a piece] and view the microcosms within it."

Image: Courtesy Photo

Image: Courtesy Photo

Smith, 53, credits her sensibility, sense of scale and ability to create worlds within her work to her upbringing in Baltimore. Her mother was a fashion designer, and "my whole family is creative," she says. "My grandfather had an amazing garden in the middle of urban Baltimore. He grew all kinds of stuff in this 8 foot by 10 foot yard with a chain link fence. My grandmom had roses and irises that were as tall as me. I didn't realize it was small. I went out there and thought I was in a wonderland.

"It molded how I view wonder in the everyday and in urban settings," she continues. "The poetic and the floral and the divine exist everywhere. My family impressed that on me even before I went to art school."

Image: Courtesy Photo

Image: Courtesy Photo

Smith's pieces—which have been displayed at museums like the Baltimore Museum of Art, MoMA PS1, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the National Portrait Gallery, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, The Newark Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art—often include graffiti and calligraphy, and she says that some early writing about her work focused on those elements.

"My work was discussed as being out of the streets," she says. "I talked about consumption and glut and overproduction and how clothes get shipped, but I also spoke about ritual and totems and different nomadic traditions where you take everything with you. The complexity of that was simplified. But there's a different conversation around Black art that's developed in the last 10 years. This is my 30th solo show, and I'm thinking about the future, and where I'm going from here, and I want to set the record straight: There's a lot more going on [in my work], and I'm a lot more vocal about it. Graffiti and Baltimore and growing up there in the '80s and the magic I experienced there with my family—all of that is potent and real, but there are other sides to that in me."

Image: Courtesy Photo

Smith says that when The Ringling approached her about doing a show, it took her back to her art education. "Within art history, especially Western art history, there's a lot of focus on European art," she says. "I have already been in that dialogue—there's always been art history behind my work. There's a classically trained hand that's fully aware of the figure and how to render it, an awareness of the history of fabric and the materials I use. There's a deeper conversation I'm having with our society—it's very deliberate how things are tied and draped and flounced. They're always relative to European art, in a way, because of the presence of cloth and the drape within those paintings. So it made absolute sense for [this exhibit] to be in dialogue to explore where they connect and where they diverge as far as timeline and culture.

"It's also about my gaze—most of these works were created or commissioned by white Europeans, and then there's me, a Black woman who grew up on the west side of Baltimore," she continues. "We're looking at each other. I think this show is bringing out nuances in the [Old Masters'] paintings that may not have been seen and in my work that may not have been seen. It's a lot of conversation. A lot of it is John Ringling's taste, too. He seemed to look at the world with a magical eye. I think of him as a ringmaster. He had an engagement with enchantment."

Image: Courtesy Photo

Smith says she hopes the show and the placement of her pieces at The Ringling will allow viewers to see themselves as a bridge between her work and the paintings. "I always consider the way the viewer looks—where the eye goes, how the body moves through space," she says. "That's emphasized in how the works are placed through these rooms, how you walk through that space. I hope that the viewer might start to feel themselves as part of all the art in the room—to see themselves, or feel a memory—and if they don't feel connected, to question why not and how we are different."

Shinique Smith: Parade is on view at The Ringling through January 2025. Smith will return to Sarasota as a keynote speaker for the Ringling's Wonder Symposium in June, as well as for a performance in the fall. For more information, click here.