Joe Volpe Has Big Plans for Sarasota Ballet

The date was Sept. 29, 1965, and Mirella Freni was pacing backstage at the Metropolitan Opera, her emotional temperature somewhere between paralyzing fear and abject terror. It wasn’t just that the Italian soprano had been cast as Mimi in Puccini’s La Boheme, the signature role of many a diva, Maria Callas among them. At the Met, Freni was also a fish out of water, awash in the loneliness and isolation that is the special province of first-time U.S. visitors who speak almost no English. Worst of all, she was about to perform on the biggest, most important stage in American opera, and before one of the world’s most unforgiving audiences.

“I can’t believe it, what I had inside,” Freni recalled many years later. It was epic anxiety of the sort that left one liable to superstition, and soon enough the soprano found herself scouring the stage floor for a bent nail, long considered a good-luck charm among Italian singers. (Luciano Pavarotti used to have them sewn into his costumes.) For some time, Freni’s search proved futile. Then:

“Suddenly, a man stood in front of me,” she remembered. “He said”—Freni descended to a basso, channeling the ghost in Don Giovanni—“‘are you looking for this?’” Seemingly out of thin air, a young Met carpenter had materialized before her. “Voilà” he said, handing her a nail. That the carpenter’s gift brought Freni abundant luck may be inferred from the rapturous reception the soprano received later that night (“the audience all but tore the house down” wrote one reviewer). But good fortune smiled on the giver, too. A few decades later, that same carpenter, Joseph Volpe, would be named head of the Metropolitan Opera.

None of which would matter very much to Sarasotans, were it not that Volpe has become the executive director of the city’s ballet company. Hiring one of the highest-profile, most successful arts leaders of our time last year was a coup for Sarasota Ballet, to say the least, and one that comes with consequences for the 30-year-old company. The ballet, like the Met before it, may well find itself transformed by Volpe, whose approach to arts leadership is as nuanced and compelling as the path he took to that leadership. Indeed, the one is unthinkable without the other.

“No,” he replies, when asked whether he ever attended the opera as a child. What about when he was older? “No.” So how did he fall in love with it? “I didn’t.”

We are on the third floor of the FSU Center for Performing Arts, in Volpe’s office, whose blue-green walls recall the Gulf waters and its occupant’s passion for sailing, no small part of Sarasota’s appeal for the 76-year-old. The space is modest, especially by comparison to Volpe’s former digs, the perfect setting for discussing the native New Yorker’s early years.

Volpe’s father dropped out after his Brooklyn high school caught fire—“they sent the other kids to different schools, and he never went back,” he says—before eventually becoming a successful clothier. Young Joe completed high school but went no farther, opening an auto repair shop and working as a Broadway stagehand before joining the Met as an apprentice in 1964. There, he worked his way up the ladder, but slowly and with stealth. Constructing sets and moving scenery were his concerns, not glittering opening nights or the glories of opera. Fittingly, his conversion came not while watching a production but while fixing one.

“Corelli and Nilsson were singing Turandot, and I was under the staircase,” recalls Volpe with a smile. The music stopped him short, his hammer silenced by two of the greatest voices in 20th-century opera. “I went out and looked, and said, ‘There is more to this opera stuff than building scenery.’ That’s when it hit me.”

In the years that followed, as he rose to become the Met’s technical director and finally, in 1990, its general manager, Volpe never forgot that opera, for all its divas and genius composers, is the consummate collaborative art form, which is to say that no moment on stage is possible without the dedicated efforts of many, many people—thousands of them, from singers to directors, musicians to crew, board presidents to audience members. During the 16 years he led what is the largest performing arts organization in the world, Volpe drew on the fierce and paradoxical humanism that his background and long years of apprenticeship had forged: Everyone mattered, and yet no one was irreplaceable.

That principle applied to ushers and stagehands, and it applied to soprano Kathleen Battle, whom Volpe famously fired from the Met in 1994.

“My wife didn’t want me to do it,” he remembers. “I said, ‘I have to do it. I have to show leadership to this company.’” Battle, at the time one of opera’s biggest stars, was “ill-behaved with her colleagues,” says Volpe. “She actually prevented the rehearsals from going on.” Battle’s dismissal for unprofessional behavior made front-page news, and Volpe received his share of hate mail. On the plus side, he says, “I got faxes from all over the world. The opera directors were so happy that finally somebody stood up and drew the line.”

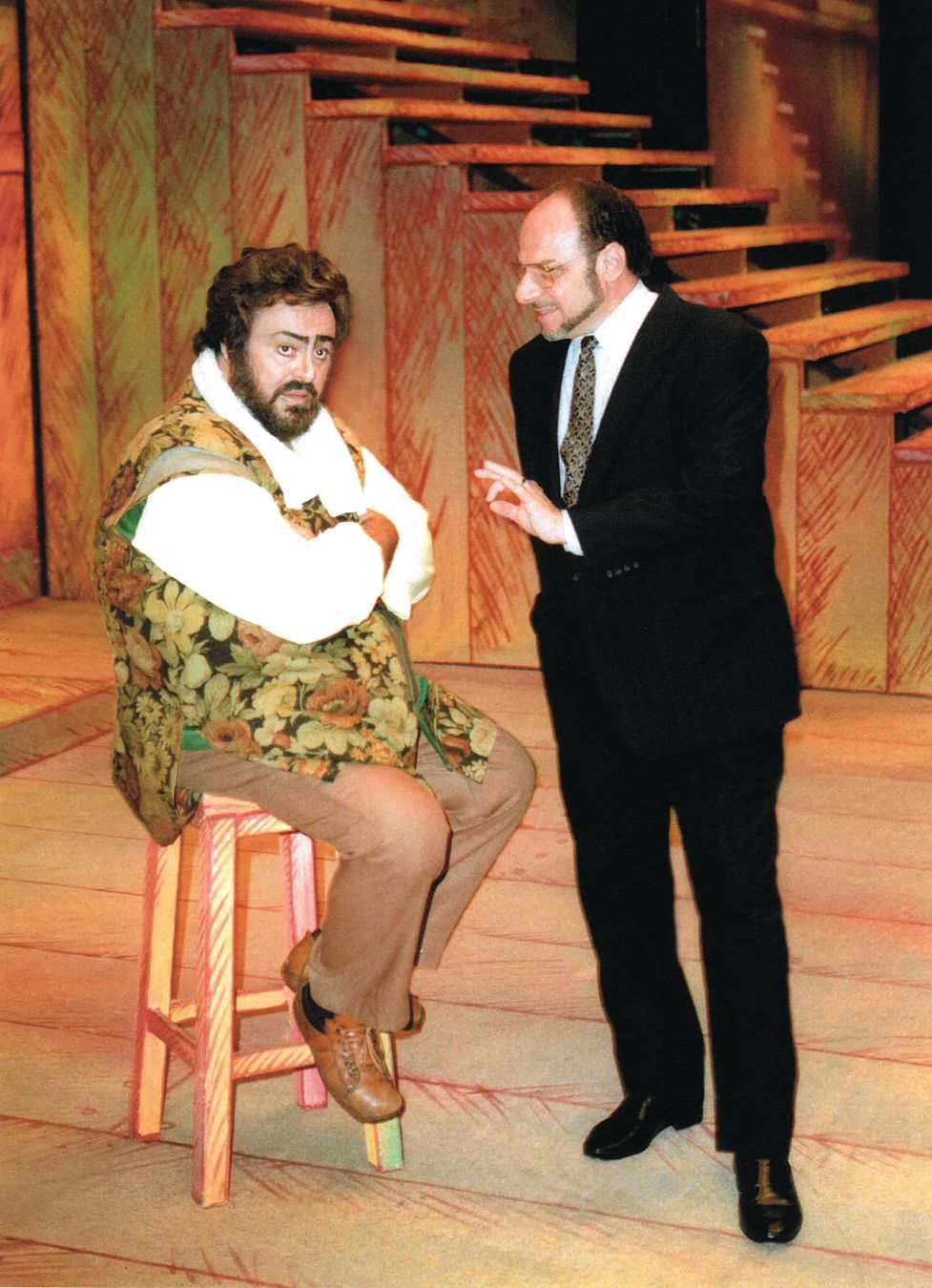

And what about that other notorious diva, or rather divo? “Look at this picture of Luciano,” Volpe says with a laugh, gesturing at a photo on the wall. Pavarotti, in full make-up, sits sulking atop a stool, perhaps threatening one of the many cancellations that were as much a part of the tenor’s career as his legendary voice. Nearby stands Volpe, delicately pleading his case.

“I’m saying, 'You know, Luciano, it’s time to go on now.'”

Volpe convincing a reluctant Pavarotti to take the stage at the Met.

Image: Courtesy Photo

There as elsewhere, Volpe was well-served by his tough-but-fair management style, that and a genius for negotiation whatever the adversary, be it one of the Met’s 16 unions, a billionaire board member or petulant director. For his efforts, the press branded Volpe a “notorious maverick” with a “legendary temper,” not to mention “feisty,” “demanding and raw-edged”—and that was just The New York Times. Still, there were no lockouts or strikes on his watch, and he left the Met with a healthy surplus. Some have contended that the institution was neither dynamic nor daring enough during his tenure, but Volpe is certain he left it better than he’d found it, which is more than he can say for his successor, Peter Gelb.

“Now the Met is really in a very bad position, and I think that’s quite unfortunate,” he says. For while Gelb has “done new and innovative things,” Volpe allows, “a lot of it isn’t working for the audience.”

To Volpe, who considers paying customers to be a constitutive part of an arts organization’s ecosystem, this is a cardinal sin. They are crucial to making powerful art possible, as crucial as anything that happens onstage. And healthy audiences, he maintains, require a diet rich in both the novel and the familiar, L’Amour de Loin and La Traviata, experimental and naturalistic, spare and opulent. “You have to balance it,” he says. Otherwise, well—“Today, Met ticket sales are the lowest they’ve been in the history of the Met,” he says. “You can blame the audience or the population only so much.”

As noted in his thoroughly entertaining autobiography (title: The Toughest Show on Earth), Volpe has been a visitor to Florida since childhood, but it was as an audience member, a few years back, that he truly fell in love with the place.

“I think he was quite shocked when he came to one of our performances,” says Iain Webb, Sarasota Ballet’s director. “He realized we’ve got something very different going on here, and he likes that. He likes that challenge.”

“This is a very unique company,” agrees Volpe, who joined the ballet board in 2014. “And Iain is a very unique director.” On the evidence of some critically acclaimed performances last year at New York’s Joyce Theater and New England’s Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in 2015, the dance world is beginning to share Volpe’s assessment. “The flame of dance inspiration passes from place to place,” wrote Alastair Macaulay in The New York Times last August. “Today I’m tempted to ask if the torch is being passed to Florida.”

Behind the scenes, meanwhile, Volpe and Webb appear to be getting along famously. The two men share a passion for growing Sarasota Ballet—its reputation and its audiences—as well as working-class, up-from-the-bootstraps biographies.

“He’s been there with his sleeves rolled up,” says Webb. “And to be honest, that’s kind of how I was brought up as well. [Webb grew up in the north of England with a fireman father who did not support his becoming a dancer.] There’s that connection of really knowing where you come from. I had to fight for every single thing I ever got.”

As for Volpe, “He came from a carpenter”—Webb goes on, his voice so awestruck, for a moment you aren’t sure if he’s talking about Volpe or Jesus—“and built himself up to run the most successful period of the Met’s life.”

Did Webb have any trepidation about hiring a man the Financial Times once called the “theater manager from hell”?

“I didn’t hear that quote,” he says with a laugh, recalling a phone conversation in which he told Anthony Russell-Roberts of Volpe’s hiring. “‘Wow, that’s something,’” replied the former administrative director at the Royal Ballet in Great Britain, who’d previously negotiated with the Met. “And then there was a silence,” Webb recalls.

“Then he said, ‘So, is he supporting you?’” Absolutely, Webb replied.

“‘Oh, perfect, because otherwise I was going to say start packing,’” said Russell-Roberts, calling Volpe “‘incredibly hard but fair.’”

It’s unclear how much of that hardness led to staff changes at the ballet over the past year. As the Sarasota Herald-Tribune reported in December, seven members of the company’s small staff either resigned or were let go, actions which Volpe termed “normal turnover,” according to the newspaper.

Webb is banking on more positive contributions from his executive director, and Volpe has delivered in ways big and small. For a January fund raiser, Volpe raided his rolodex, securing performances by American Ballet Theatre principals and mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade. Other efforts have focused on continuing to raise the company’s profile. “They only have six programs a year,” Volpe says. “I thought, to increase their visibility, they should do more touring, so we established a touring fund.”

The touring also ensures dancers have more work, he says. “That’s one thing. Second, I want to establish some kind of endowment to where they have financial stability, which the company doesn’t really have now.” In addition, Volpe has proposed relocating the ballet’s school and conservatory—currently housed in a building north of the airport—to a campus of its own. That would require the construction of more rehearsal studios and office space, and of course, another fund. And he is actively involved in discussions over Sarasota Bayfront 20:20, a project in which the ballet is a stakeholder. “I want the company to have a say in where the new performing arts center is located,” Volpe says.

Of course, almost everything the company envisions will require more money in the years ahead, from pay raises to health insurance for the dancers, both of which Volpe recently secured. And at press time, the company’s dancers voted to unionize, which could lead to more costs—although Volpe accepted the news with equanimity.

But here, as elsewhere, his managerial compass has hardly wavered since his Met days. He still favors personnel over profits, human capital over the other kind. For Volpe, the pleasure comes in going to his rolodex and soliciting a world-famous orthopedic surgeon’s advice on a dancer’s injury, or in telling Margaret Barbieri—Webb’s wife and the ballet’s assistant director—that she needs to stop pushing herself so hard, even if it is the middle of the season.

“He just puts his arm around her, hugs her, and says, ‘You’ve got to take some time,’” Webb says. “He’s got an amazing heart of gold.”

That and a keen sense of what great art demands. Which is to say people. Lots and lots of people.

Houston-based Scott Vogel, vice president of editorial content for SagaCity Media, is a former arts writer and editor at the Washington Post.