Finance Industry Vet Ed Swan Jr. on the Wealth Gap and the Healing Power of Art

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

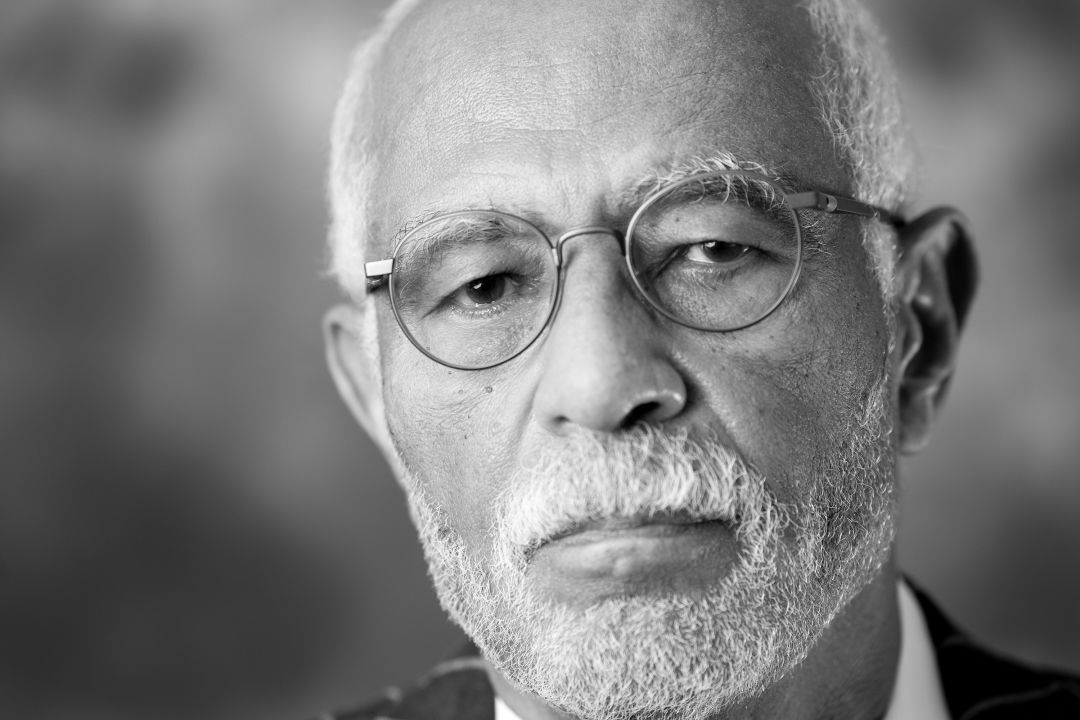

Ed Swan Jr.

Image: Michael Kinsey

Ed Swan Jr. was born and raised in Detroit. In 1959, he left for Tufts University in Boston, then went on to get his MBA at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He also served as a captain in the U.S. Air Force, stationed in Las Vegas.

Following his time in the Air Force, Swan worked in institutional asset management for more than 40 years with well-established financial firms such as MFS Investment Management and UBS Asset Management. From 2000-2002, he was a professor in Florida A&M University’s School of Business and Industry, where he developed innovative investment management courses.

Swan has served on many boards, including the New York City Industrial Development Agency, the Massachusetts State Finance Advisory Board and the boards of trustees for Dillard University and his alma mater, Tufts University. He is also active with the men’s fraternity Sigma Pi Phi, known as Boulé.

In 2011, Swan and wife Claudia moved to Sarasota, where he serves as treasurer for the Ringling Museum of Art, and works with the Hermitage Artist Retreat on marketing and outreach. Now 79, Swan is retired and enjoys time on the tennis courts and in his woodworking studio.

Tell us about your family.

“My mother grew up in Cleveland. In her era, Black women had few job options with upward mobility—mainly teachers or social workers—so she got her masters in social work, and worked for the American Red Cross, helping World War II and Korean War veterans. She was also active in picketing to desegregate Cleveland restaurants.

“My paternal grandfather brought his bride from Bermuda, and graduated from the University of Michigan Law School in the late 19th century. Our family believes that he was the school’s first Black graduate. He later became a Detroit judge with two children—my father and uncle. He died at an early age from cancer, and by the time their sons were in high school, my grandmother had died, too. My father and uncle worked on the Great Lakes as porters on summer cruise ships to put themselves through college. Often, they would have to drop a semester to bank enough money to go back.

“My father took a senior position with the Roosevelt administration at the Fair Employment Practices Commission in Michigan, where he helped place women and people of color in jobs after World War II. Later, he became the executive director of the Southeastern Michigan NAACP branch, which he built into one of the largest in the country.

“On a trip to Bermuda, when I was 7 years old, my father stopped into the NAACP offices in New York City. While there, I met Walter White, the longtime legendary leader of the organization. I feel lucky to remember that meeting.”

Civil unrest in Detroit began in the 1950s. Tell us about being a teenager during that time.

“There were fairly strict patterns of racial segregation in the 1940s and ‘50s. In that era, Detroit was a remarkable place to grow up. The city had a reasonably stable industry post-World War II, which helped evolve a middle-class Black community with Black doctors and lawyers.

“Dearborn, which borders Detroit, was a sundown town run by Mayor Orville Hubbard, who was strongly opposed to desegregation. It had such a terrible reputation that, nearly four decades later, when it was time for my mother to move into a retirement community, we looked at a very nice place there called Henry Ford Village. Even though she had friends there, she was reluctant to move because it was in Dearborn. The city evolved over the years, but just the idea of being there was repugnant for my mother. Those scars run deep.”

What was it like moving to Boston from Detroit to attend Tufts University?

“I had two interesting introductions—first, by a ‘random’ stroke of luck, the only other Black male student and I were placed as roommates. Either way, this was fortuitous because he was a wonderful human being.

“My family didn’t have money for me to visit the campus before I moved. I knew no one and felt totally lost. While registering, a little guy came up to me and asked if I was ‘coming out for track.’ I said that I didn’t know, but he pressed. ‘You oughta come out for track,’ he said. ‘I’ve never met a Black kid who can’t run.’ He had a local Black track star on the team, so he made a sweeping assumption.”

What inspired you to serve in the military?

“In high school, I was commander of the city-wide junior ROTC, which led me to join the organization in college; it was something familiar in that new environment. After two years, I joined the U.S. Air Force, where I accepted a second lieutenant commission that committed me to four years of service."

Were you embraced by your fellow white service members?

“I was stationed in Las Vegas where, as a Black man, it was difficult to find housing. I was one of five Black officers on the base and ran the base management information office. While there, I had only a few racial problems. One notable incident happened during summer training, when I received an award for ‘outstanding cadet.’ After the ceremony, while having dinner with three other cadets, one of the guys at the table dropped the N-word. It took great restraint for me not to talk about his mother and the status of his birth in return.

“Once in a while, a white airman would walk by without saluting me and I would ream them out. In the scheme of what was happening during the civil rights era at the time, it was annoying, but I didn’t see the worst of it. What I faced was minor in comparison to the Black people who were trying to ride buses and go to school and vote.”

According to Market Watch, only 6.9 percent of those in the financial world are Black. That number must have been significantly lower when you began working in 1975. What was it like getting into the business at that time?

“Diversity was not a relevant concept then, and the industry was not particularly welcoming. For the first five years of my corporate career, I was the only Black person in the room. During an interview with a well-known Wall Street firm partner, he said, ‘Well, we’ll hire you, but you won’t ever be a partner.’ While I appreciated the candor, it was shocking.

“Looking back, MFS Asset Management was more welcoming than any other institution I worked with, which was to the credit of the president and CEO Coy Eklund. It truly does trickle down from the top. He conveyed to the leadership team that in order to serve a broad population, from gender to ethnicity, meant the firm must embrace diversity while hiring the best employees.

“Like other business goals, this directive was measured by performance, and compensation reflected your success. That is how to inspire change. You’re not going to have change until people’s pay is tied to that change. It’s wonderful to affect people’s hearts and minds, but unless compensation is tied to meeting diversity goals, change may move at a slow pace.”

Did you experience any racial discrimination while climbing the corporate ladder?

“While I worked in New York City, it was a common occurrence for me to see a white woman clutch her purse as I approached, oftentimes while in an elevator. Now, I was presentable—I had my shirts and suits custom-made, with my shined shoes and briefcase. No matter the class signals I would send, as a person of color, the overriding caste signal of my skin color represented that I was a danger in this society.”

How did you balance your work life and your personal life?

“Being in the finance world is intense, but there’s more to life than just that. So I turned to the part of me that wanted to create something beautiful and functional, and I wanted to do that in a medium that allowed for contemplation. I’ve always enjoyed good design and, about 30 years ago, discovered that drawing furniture came naturally to me. Going into my woodworking studio to create in relative solitude—taking an image I designed and turning it into something tangible, from start to finish, on my own—was a rewarding artistic outlet.

“A third side of my psychic balance is helping people. Early in my career, I helped develop an organization called Minority Interchange that was dedicated to helping minorities with shared challenges succeed in the insurance industry in my community. We provided everything from career counseling to network-building support. Later, I created a similar model for the investment industry.”

It’s difficult for Black people to build wealth in this country. How can we level the playing field?

“We must begin by addressing unconscious bias, which is largely derived from a misunderstanding of folks who are not like us, or out of fear, or from being fed information that is less than complete. When we allow people to be diminished in our eyes without thinking critically, it hurts everybody.

“Because of this, I believe in universal national service for all between the ages of 17-25 years old—Black, white, tall, short, rich, poor, high school or college grad. Everyone should do a stint in a national service where they have to interact with people who are not like them. This would be a vehicle for our fellow Americans to become aware of everyone else’s essential humanity.

“Some may be irredeemable bigots, but those are few and far between. Most people fit somewhere on the positive side on the scale of human decency.”

What do you want your white friend/neighbor/colleague/community to be doing right now?

“My thoughts go beyond white folks and non-white folks. I want it to be recognized that how we treat and care for each other is more important than how much money we accumulate and attempt to protect.

“The reality, in its most stark terms, is that our society cannot grow healthier and more welcoming with a concentration of wealth and opportunity in the hands of a relative few. Especially when those few are defined by gender, ethnicity, religion or status at birth. All of us are in the same boat. If too many are on one side of that boat, eventually the boat will tip over.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill