Activist Barbara Nell Langston on the History of Newtown and the Importance of Voting

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

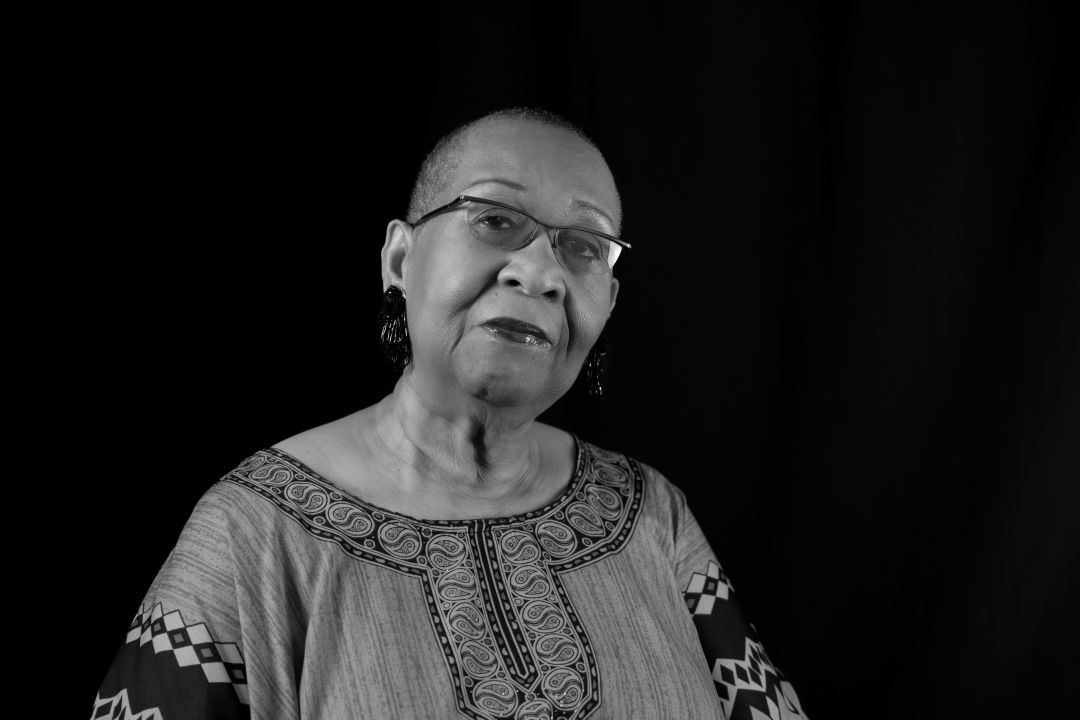

Barbara Nell Langston

Image: Michael Kinsey

Barbara Nell Langston has spent her life making sure a Black voice is always at the table when it comes to her beloved Newtown neighborhood, where she’s lived since 1953. Now 71, Langston is considered a village elder. “I live the village life, which is Newtown,” she says. “I live the stories of this community, and I love it here.”

Newtown leaders like John Rivers, Dorothy Smith, Robert Taylor, Carl Stevens, Ed James Sr., and Jerome Dupree were her personal mentors. They inspired her work with various city and county committees, including the Amaryllis Park Neighborhood Association and the Front Porch Florida program, an initiative by then-Gov. Jeb Bush to revitalize underserved communities around the state.

Langston’s work with the Front Porch partnership was instrumental in securing redevelopment funds for Fredd Atkins Park, Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Park, the Robert Taylor Community Complex, Booker High School, the construction of Janie’s Gardens, the Newtown Medical Clinic, and redevelopment of the Dr. Martin Luther King corridor.

Langston also championed a Black history room at Booker High School, which features memorabilia from Newtown’s rich history. “I tell every student that this is the history of your school,” she says. “If you don’t know where you’re coming from, then you don’t know where you’re going.”

What brought your family from Soperton, Georgia, to Sarasota?

“My mother, Pearl Jackson, wanted to get her three youngest children out of Georgia because of the lynchings. She never wanted us to witness one. I was 4 years old when she brought us to visit my aunt, who lived in Newtown. She liked the supportive Black community here. It was self-contained, with a supermarket, schools, a community center and citizens who stood together. My dad did not want to leave Georgia, so my mother moved without him. That’s how serious she was about refusing to raise her children in that environment.”

What was it like for you and your family here?

“I was raised on 32nd Street, where my mother rented a home that was owned by a white man but managed by a Black man. One day, the owner knocked on our door and told my mother that we were being evicted for non-payment. In the Black community we are taught to keep copies of all transactions. She invited him in and showed him copies of her receipts.

“The next part was one of my first experiences learning that there are good white people out there. It turns out that the manager had not been passing our rent money on to the owner. The owner said to my mother, ‘Ms. Jackson, I’m going to sell you this house. And all of the rent you have paid will be your down payment.’ That was something.”

Was it difficult as a child to grow up Black in Sarasota?

“When the Black community says, ‘It takes a village,’ it’s true. I remember our first nursery school—the Black teachers were like pied pipers going up and down the streets. Every morning and after school there would be a parade of children that the teachers would collect and return safely. I had a wonderful upbringing here. Everyone turned out for life events and intermingled.

“But we were not allowed to—and did not—cross the railroad tracks into the Central Cocoanut neighborhood, which was all white. To get around that, buses ran every 30 minutes so our parents could get to work in the white community. But when integration came in 1967, that changed. We could move into that neighborhood, but Black people were still terrorized.

“One day I was walking with some friends beyond the desegregated lines, when a carload of white people threw junk at us and told us to get our ‘Black pickaninny asses’ back across the tracks. I’ll never forget that. It still bothers me today.”

Why have you been a staunch proponent for preserving Sarasota’s Black history?

“If we don’t hold up and hold on to our history, it will be gone. I was so proud when it was my turn to step in and carry the community values that were instilled in me. The elders—who all called me ‘baby’—held me accountable. Even though the process was a battle, it was a proud moment for me to honor Newtown’s pioneers by sitting on the planning committees for Booker High School and the Robert Taylor park.

“I take my community liaison role seriously. I’ve sat on every board that I could and traveled all over the state. I educated myself and got training wherever available. One example is Asset Based Community Development (ABCD), a strategy for sustainable community-driven development co-founded by John McKnight with two famous graduates: Michelle and Barack Obama. McKnight taught us that change flows through and from citizens. ABCD trained us how to work with city leaders for economic development, to be ready with information when we sit at the table, and to fight for what we want in our community.

“Even so, it was a struggle with the City of Sarasota. Everything was a fight, like being told that funds were not there for the Black community’s schools, but that at the same time, the money was there for certain white schools. And when it came to our parks, they told us what kind we could have, but those parks were not what we wanted or needed, so we said no.

“With the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Park we were promised many things, but in the end the park barely looked like the original plan. We saw an income opportunity in having a building with a commercial kitchen on site. We could rent the space for festivals, cooking classes, family gatherings and even food truck vendors. That was agreed upon with the city, but instead of our commercial kitchen, we got a regular stove and refrigerator. And during a recent redesign, it was all torn out, because for some reason the city decided to expand the bathrooms. We no longer have a kitchen. Now it’s a small room with a commercial microwave. That was an insult.”

Until 2016, Newtown wasn't recognized by the Florida Department of Transportation. How did you work to literally put Newtown on Florida road maps?

“Bill Nichols of [the city’s] Public Works Capital Projects and I began our work in 2011, and it took five long years to receive the designation on Florida road maps. I was determined to make it happen. We had to overcome many roadblocks. One was when we learned that the City of Sarasota had overlooked incorporating Newtown when it was platted in 1914. It had originally been called Overtown—also known as Black Bottom—when settlers arrived in the late 1800s.

“In 2016, we were finally approved after meeting FDOT criteria, going through a permitting process and installing two community markers on U.S. 301. Now the community of Newtown appears on the Florida map. This was a significant achievement for our historic, century-old Black community.”

What do you say to Black youth, who might think their vote doesn’t matter?

“I’m dedicated to political education, the Get Out the Vote movement and making calls to encourage early voting. What’s happening in this country now has to be a lesson for those who don’t think their vote matters. Your vote is the most important thing you have. As important as the presidential election is, it’s also necessary to vote locally—from county and city commissioners to the governor—these people make decisions about what will happen in your city, and it will affect your everyday life.

“The Black community is often underestimated by politicians. What they don’t know is that we learn everything we can about the candidates—such as if they work for what our people need and who supports them financially. We know every developer’s candidate. As my mother told me in 1967, ‘Barbara Nell, you don’t vote party, you vote candidate.’

“All Black people have to learn that their vote is important. If it’s not, then why do they try so hard to take that vote away? Some didn’t vote in the last presidential election, and that’s why we got what we got. This is the moment for change. Voting is how we will have the country we want.”

What is your advice to the next generation of Newtown activists?

“Our future is in your hands. I can do for the young what my mentors did for me, but you have got to fight for what you are after. Marching without action won’t accomplish anything. The next generation must make sure someone is at that table—that’s what we did in my time. Don’t stop until you get what you came for. It is your time. You gotta be in the fight.”

What do you want your white friend, neighbor, colleague and community to be doing right now?

“Stamping out racism starts with each and every one of us, but its success will depend on everybody coming together. Racism is taught. I remember watching the civil rights movement on television in our home on 32nd Street. My mother was sure to point out all of the races and all of the colors fighting for justice. She told us that we don’t hate anyone, and that if we didn’t like what’s going on, it was our job to do something about it. I’m still like this today. So I share my mother’s advice here—don’t sit around and talk. The white community should get up and take action.”

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill