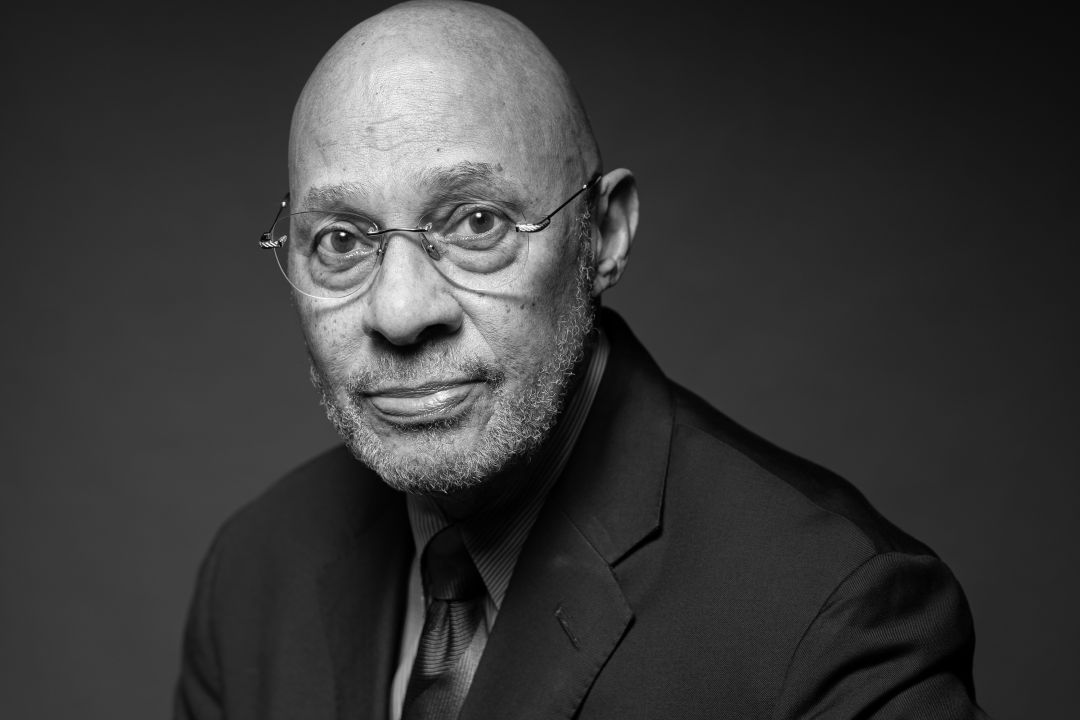

Former Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer on Public Service and Race Relations

This article is part of the series Listening to Diverse Voices, proudly presented by Gulf Coast Community Foundation.

Dennis Archer

Image: Michael Kinsey

Lawyer, author and former Detroit mayor Dennis Archer takes great pride in his Michigan roots. Born in Detroit, Archer earned his law degree from the Detroit College of Law, now the College of Law of Michigan State University, in 1970. In 1971, he opened an all-Black firm with three other partners.

In 1985, Gov. James Blanchard appointed Archer to Associate Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. Archer was elected to an eight-year term the following year; during his tenure, he was named the most respected judge in the state. In 1990, he stepped down to run for mayor; David Axelrod, who went on to become President Obama’s chief campaign strategist, ran Archer’s campaign.

During his time as mayor, from 1994 to 2001, Archer attracted billions in new business to Detroit and secured $100 million in federal Empowerment Zone funds, which are used to uplift distressed urban communities. He was named one of the 25 Most Dynamic Mayors in America by Newsweek, one of the 100 Most Influential Black Americans by Ebony, and one of the 100 Most Powerful Attorneys in the United States by the National Law Journal. In 2000, he was named Public Official of the Year by Governing magazine.

Archer has also served on four bar associations, including as president of the American Bar Association, which barred Black members until 1943. He was the first Black person to serve in the position.

Today, at 79, Archer is Chairman Emeritus of the Dickinson Wright law firm in Detroit and winters in Sarasota with his wife, Trudy DunCombe Archer, retired judge for Michigan’s 36th district court. Archer also serves on the board of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art and the advisory board for Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe.

What was your childhood like?

Cassopolis, where I grew up, was 187 miles from Detroit with a population of 1,200 and three factories. It was also a stop on the Underground Railroad for slaves to make their way to cross the Detroit River into Canada. I still remember the day that my father pulled the car over and pointed out the land where the railroad once was.

Tell us about your parents.

"My dad had a third-grade education and my mother had a high school diploma. They made it clear to me from an early age that I would go to college. But they couldn’t tell me where to go because they had never set foot on a campus.

"My dad worked for a man named Fern Westcott who owned a tool-and-die in South Bend, Indiana. He made $75 every two weeks for six months; after that it was reduced to $37.50 every two weeks. During those lean months, I’d hear my dad say that he had to go to the Department of Social Services. I didn’t know what he meant by that then, but now I know it was to put food on the table.

"He had a summer home on Diamond Lake in Cassopolis; it was a pristine, beautiful lake. Not one person of color owned property there, nor were we allowed to swim in the lake. We didn’t have running water at home, so I always enjoyed going with my dad to Westcott’s home where I could take a shower.

"Nearby Stone Lake is where we swam and where Black people owned cottages. Black kids would come in to go to Camp Baber in the summertime."

When did you become aware of the civil rights movement?

"In 1954, while at church, I learned about Brown v. the Board of Education. I listened as the folks in church talked about this lawyer named Thurgood Marshall who would make a difference by giving the Black community access to better education.

"Aside from that, I didn’t have a sense of it until high school when my uncle brought us an old television. That’s when I had the chance to watch the news. I learned about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Blacks conducting sit-ins at lunch counters, and the Black activists who were hosed and beaten because just because they wanted the right to vote. And it’s where I first heard of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr."

Tell us about experiencing Detroit’s speakeasy race riot in 1967.

"My father-in-law and I returned home from an round of golf that morning, and we could see smoke. As we drove closer, we could smell it. When I dropped him at home, I learned that in the early morning hours, the police had raided the blind pig, an after-hours joint where the city’s Black residents would go.

"The police arrested 85 people but didn’t have enough paddy wagons. By the time the transport arrived, a mob had gathered, and someone threw a bottle that launched five days of rebellion, riots, fires and destruction, leaving 43 people dead. Gov. George Romney called for thousands of Army troops, National Guardsman and police.

"At that time, I thought segregation was only in the South because of what I saw on television, but I quickly learned about discrimination against Blacks."

What did you learn about racial discrimination while working at a law firm?

"I saw for the first time how much power lawyers had to represent minorities who could not represent themselves.

"When I got ready to graduate law school, I was invited to interview with a big law firm. After the interviewer and I said hello, he politely told me that the firm didn’t hire lawyers from the Detroit College of Law—only from University of Michigan, Harvard, Yale, etc. I thanked him, and as I walked outside, I smiled to myself because I had done the research on the interviewer. He had graduated from the same college as me. There were no Black lawyers and even fewer women in any large law firm in the State of Michigan.

"Many Black lawyers didn’t get the respect they deserved at white law firms, so some started their own firms. But they would also have to work a full-time job until they built a clientele. Some had to practice law long after they should have retired."

In 1994, during your first year as mayor, Congress passed the controversial Crime Bill. Many say it undercuts justice reform. What do you think?

"I was one of the supporters of the Crime Bill, and then-President Clinton had the support of the United States Conference of Mayors. At that time, all major cities had a huge problem with crime and needed more police on the streets. And we all lobbied Joe Biden—then the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee—to get it passed.

"What nobody anticipated was conservative Republicans amending the bill and the unintended consequences that came on the state level, which negatively affected people of color. When I became American Bar Association president, 65 percent of those in U.S. prisons were Black or Hispanic. More time was being given to the minorities."

Tell us about your relationship with Clinton.

"When I became mayor, I got involved in Clinton’s presidential election. I met him through Rodney Slater, who later became President Clinton’s Secretary of Transportation, at a National Bar Association annual meeting.

"I grew close to the president—so much so that I stayed at the White House twice, once in the Lincoln bedroom. If I left a message for Clinton, he would return my call, even when he was out of the country."

Dennis Archer with civil rights icon Rosa Parks. Archer was appointed Parks' legal guardian in 2004.

Image: Courtesy Dennis Archer

In October 2004, you were appointed legal guardian to civil rights icon Rosa Parks. What was she like?

"Rosa Parks learned about a song named for her while she was at church. In March 1999, she filed a lawsuit—Rosa Parks v. LaFace Records—against American hip-hop duo OutKast and their record company over their song 'Rosa Parks.'

"I was asked to consider being her guardian by a federal judge, and I agreed to it. Rosa was someone I admired and respected long before I met her. When I was in high school, I read about when she was arrested because she wouldn’t give up her seat on a bus. She and her husband both lost their jobs as a result.

"She was just as wonderful and thoughtful as could be. Everybody loved and respected her. She started a foundation called the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development for youth development and civil rights education and advocacy. She was a remarkable person; it was humbling to represent her. Not long after the OutKast case was settled, she passed. By that time, we had been acquainted for nearly four decades."

As you consider the state of the U.S. today, what do you think would improve race relations?

"We have gone through a period that I’ve never seen the likes of. We have witnessed discrimination against everyone from lawyers of color to U.S. presidents. During this period, many have taken a closer and different look at society and racial issues. Diversity, equity and inclusion are important not only in terms of what we do and what we have, but what we want to change.

"Look at corporations that, after the events of Jan. 6, pulled funding from politicians who used money to perpetuate falsehoods. Corporations can make a difference on issues from race to gender, especially if they look at their hiring practices. One way is to put more women on boards—one study showed that when corporate boards had female representation, those boards did better for the shareholders.

"Throughout my career, it has been a priority to help minorities, including women. For those of us who have been successful, it’s important to open doors for those who come behind us. It will make a difference."

Listening to Black Voices is a series created by Heather Dunhill