Brilliant, Imperious and Public-Spirited, Philip Hiss Helped Establish Sarasota’s Claims to Fame

Of all the fabulous characters who made Sarasota what it is today, Philip Hanson Hiss is the great mystery. He’s been vilified, glorified, misunderstood and nowadays almost forgotten. Was he an architect? No—although the buildings he commissioned and helped design are now world famous. Was he a rich dilettante? Perhaps—but no dilettante ever worked so hard or got so much accomplished. A visionary educator? Definitely—New College, the institution he willed into being, has become a unique place of learning, in spite of the fact that a frustrated Hiss walked away from it and considered it a failure.

Hiss is an American archetype that hardly exists anymore, a rich man who devoted his life to public service. “He loved the community,” says architect Frank Folsom Smith, who knew him well in his heyday. “It wasn’t just his ego. He had the highest standards.”

A New Yorker by birth, Hiss hailed from an old-money, socially prominent family—several of them, in fact. One cousin was Seth Low, former mayor of New York and subsequently president of Columbia University. Another cousin was Alger Hiss, either a Russian spy or a martyr to the liberal cause, depending on your point of view. It was a connection that would bedevil Hiss at many points in his career.

After a somewhat chaotic early education (he attended four different prep schools and finally graduated from the Hill School in Pennsylvania), Hiss made an unusual decision for someone with his background. He would not go to college. He had inherited a substantial amount of money from a Low uncle, and he would educate himself. He then embarked on a series of adventures that read today like popular fiction. He bought a Harley and traveled throughout South America, keeping a journal. He journeyed to Bali, where he met Margaret Mead and studied the way the indigenous people lived, educated their young and built their houses. He published a well-received book of photographs taken in Bali and worked as a photographer in New York City. During World War II he served in the OSS, an early precursor of the CIA, and worked in the Netherlands. He also married, had two children, got divorced and then married the same woman again, then divorced her a second time.

Hiss on the yacht he sailed to Florida.

With the war and the marriages behind him, Hiss had a boat built, a 48-foot yacht named the Garuda, and he set sail for Florida, looking for a new beginning. He was 38 years old.

That was in 1948. Back then, Sarasota was a rather sophisticated place. It had an art museum, several theaters, a symphony orchestra, a group of wealthy residents and, most important to Hiss, intellectuals. Writers, painters and architects lived here. There was an active social life. He met and married Shirley Holt, whose family wintered here, and they began to raise a family: Philip Jr., Maynard, another Shirley (known by the old-WASP nickname of Muffi). Hiss bought a big, empty, beautiful stretch of sand on North Lido Key and soon found himself a real estate developer.

He was without a doubt the classiest real estate developer Sarasota had ever seen. He took a sandbar used as target practice during the war, named it Lido Shores, and turned it into the most stylish place in town. Its sleek modern houses, designed by local architects, became part of what is now known as the internationally recognized Sarasota School of Architecture. The architects were already friends of Shirley’s, and their homes began to dot the sandy landscape, built to principles Hiss had learned in Bali.

Breezeways and overhangs were used to control the sun and breezes from the Gulf of Mexico, with wide expanses of glass to bring in the views of turquoise water. Hiss and Shirley’s friend, Paul Rudolph, who became one of the most famous modern architects of all time, designed the Umbrella House, so named because of the wood lattice that shaded the swimming pool. The house served as a model for prospective buyers.

A Sarasota School of Architecture Hiss residence.

Hiss also designed a home for his family. It was large and elegant and soon became the most glamorous house in town. Also noteworthy was the studio Hiss and Tim Seibert, another Sarasota School practitioner, designed. It was built on stilts and had the novelty of being air-conditioned, a necessity to protect the papers and documents it housed.

The family soon became part of the life of the town. Their home was a perennial feature of house and garden tours, and both Hisses served on boards and committees. They were everything Sarasota aspired to: independently wealthy, great-looking, doing good deeds, with the most impeccable taste imaginable.

Hiss was often seen around town in his distinctive Mercedes sports car with gull-wing doors. The national press began to notice both Hiss and his buildings. The buildings were recognized as something new and important, and Hiss got publicity that sounded like his mother had written it. He was “tall and debonair” (Architectural Forum), not to mention “suave and cultivated” (Holiday Magazine). Writer Stephen Birmingham, known for his books about wealthy Americans, noted that “he is already rich and therefore has no particular interest in a quick profit.” In fact, throughout his career Hiss cultivated the image of a wealthy man in public service for the good of society, not to line his own pockets.

Hiss met all the celebrities visiting Sarasota. Here, he greets Bette Davis at The Players Theatre.

No one is quite certain why Hiss decided to run for the school board, then quaintly known as the Board of Public Instruction. Some say he did it as a bet. He certainly didn’t expect to win. But win he did, and he was appalled by what he discovered. “When I got the facts, I went wild,” he said. The schools were poorly designed and not kept up. “The restrooms were so bad the kids wouldn’t even go to the bathroom.”

Hiss was the only Republican on a board of Southern Democrats, and at first the going was tough. As architect Gene Leedy recalled, “Every vote was 4 to 1 and he was the 1.” But Hiss talked friends and allies into running for the board, and soon he became chairman. He was somewhat of an autocrat, Leedy said. “The meetings lasted just 15 minutes because he had it all worked out.”

Hiss’ views on education changed during his time on the board. At first he was conservative and railed against “progressive education.” But the more he learned, his views evolved into something much more liberal. He advocated for—and got—a much more creative educational program, with special classes for gifted students, an expanded art curriculum and more academic freedom for teachers.

But what made him noteworthy as an educator was the relationship he saw between education and architecture. He felt that a school building could actually “teach,” and went on to prove it with the construction of nine new Sarasota schools between 1952 and 1960, each one designed by the talented young architects who had been designing houses for him in Lido Shores.

Alta Vista Elementary School

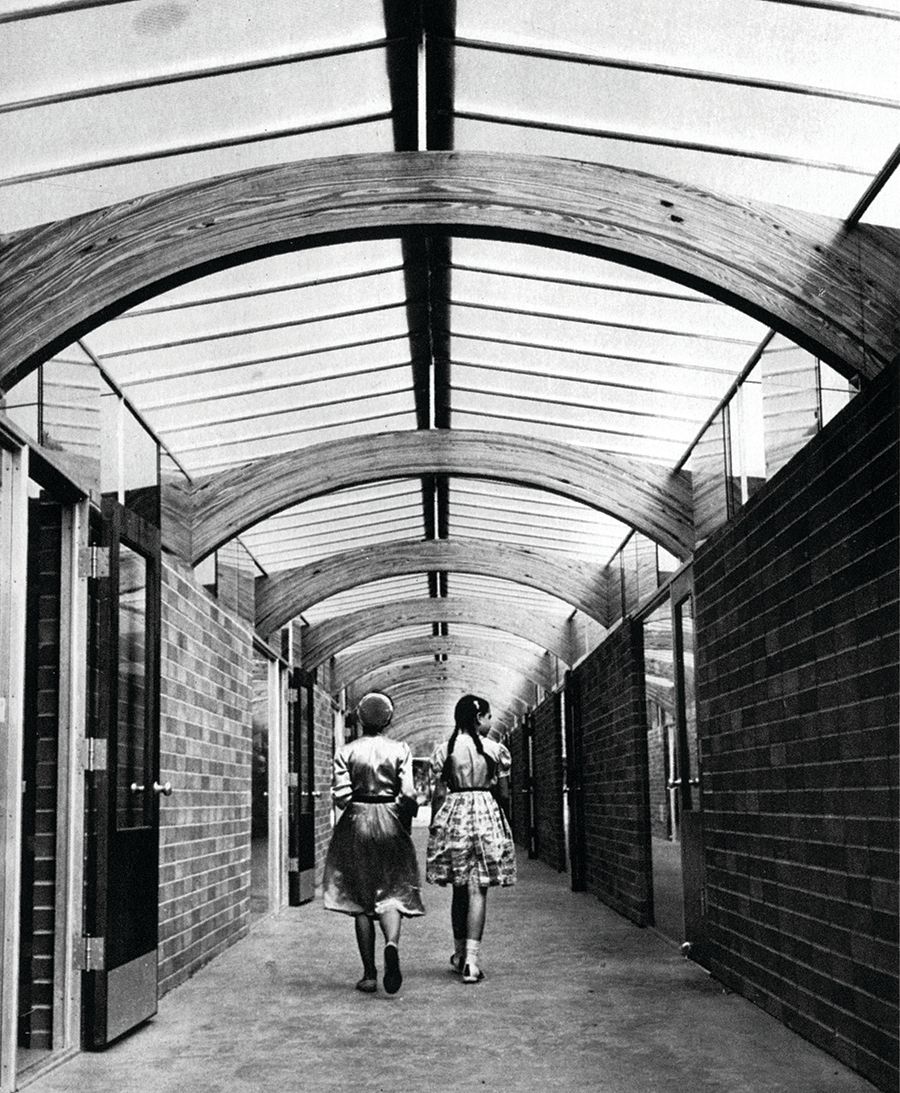

Some of these schools were remarkably innovative. Englewood Elementary, designed by Jack West in 1959, used a cluster plan with flexible spaces. The students were not put in grades but proceeded at their own pace, with teams of teachers. The building’s soaring roof became an icon of midcentury school design. Other schools featured “butterfly wings of laminated wood” (Alta Vista, designed by Victor Lundy); a curved and indoor-outdoor design scheme (Brentwood Elementary, designed by Gene Leedy and William Rupp). The high points of the Hiss building program were two extraordinary structures designed by Paul Rudolph. The first, a major addition to Sarasota High School, has recently been renovated and is becoming something of a tourist attraction. The other, Riverview High, a complex campus of elegant breezeways and outdoor corridors, was torn down after much controversy in 2009 and replaced with a completely new structure.

The schools gave Sarasota a starring role in the country’s architectural press, and Hiss’ educational innovations set the stage for what has become the county’s well-regarded educational system. But it was a strain on both Hiss and his family, and he lamented the pain that the “unpleasantness” caused them. Much like today, meetings could get rough, with insults slung around and tables pounded. The conservative Southern leadership of the county didn’t feel it needed improving, especially by a Yankee named Hiss.

Eventually it all became too polarizing and too political. In 1960, Hiss announced he would not run for the board again.

In a period of 12 years, from 1948 to 1960, Hiss had virtually invented the sleek modern look and the socially progressive attitude that have come to characterize today’s Sarasota. That should be enough for any man. He had dreamed big and it had paid off. Now he could rest on his laurels. But it turned out his biggest dream was just beginning.

Architect I. M. Pei and New College president George Baughman in front of a model of the Pei-designed residence halls.

Looking at the two institutions today, it’s hard to believe that famously free-spirited New College started out as a project of the Sarasota County Chamber of Commerce.

Back in the mid-1950s, the Chamber began extolling Sarasota as “a college town without a college.” This naturally prompted the idea that maybe we should get a college. Any college. A junior college was discussed. The state would pay for it. But local politics insisted it be put in Manatee County. University of South Florida was looking for a place, but they settled on Tampa. Likewise, Eckerd College decided on St. Pete. The right situation just wasn’t presenting itself.

Then a man named John Whitney McNeil got involved. He was a Congregationalist minister with a visionary bent. Today he would be called a social engineer. Plymouth Harbor, the innovative and highly influential retirement home just past the Ringling Causeway, was an earlier project. He and architect Frank Folsom Smith created a building—a campus, really—that re-thought housing for the elderly, with an emphasis on beauty and community.

It happened that the national branch of the Congregational Church had as part of its mission the founding and support of colleges. They had quite a track record. Harvard and Yale were developed with Congregationalist money. They had a special fund for colleges in the South, then considered somewhat of an educational backwater. Once McNeil got on board, the college project started to take off. Committees were formed and meetings held. One of the first meetings was attended by Philip Hiss.

Sitting in the audience, Hiss must have thought back to the glory days of his cousin Seth Low. Considered one of New York’s finest mayors, Low went on to another career after he left office, as president of Columbia College. Low turned the college into Columbia University and moved it from midtown Manhattan to a new location in Morningside Heights. The new campus was a great success and became a model of how to place a campus in an urban setting. Its centerpiece, Low Library, is a landmark known to every New Yorker.

Hiss, his school board career over and his imagination seized, immediately joined the executive committee for the college.

The idea of exactly what the college would be like was still very vague. It certainly wouldn’t be a religious institution. The Congregationalists had helped out many secular colleges, but they always stayed in the background. They did, however, have one stipulation. Every institution they did business with had to sign a pledge: Their enterprise, be it private or public, could not discriminate due to race. It was 1960 and Sarasota was just beginning desegregation, but it still remained a very Southern town. The committee thought it over long and hard. They finally decided to sign. In the context of the time and place, it cast New College as a very liberal institution.

The new college, which was conveniently named New College, was incorporated in 1959. The 18 trustees, half of them local businessmen, voted Hiss chairman. He was the logical person. In addition to his school board background and architectural expertise, he didn’t have a job to bother with (his school board term was ending), and he certainly believed in the project.

Three trustees made financial pledges. The largest by far—$100,000—was from Hiss.

They had a chairman. Now they needed a president. The search quickly narrowed to George Baughman, a Tampa native who had risen to become vice president for finance at New York University. Hiss was impressed with Baughman’s enthusiasm and financial acumen. He was offered the job and accepted.

Baughman was getting what sounded like a fabulous perk. As part of his $100,000 pledge, Hiss was donating his Lido Shores home, the glamorous modernistic mansion overlooking New Pass, to the college as a residence for the president. (The Hisses were building another house nearby.) The Baughmans arrived in due course, and with great fanfare, including a full-page interview in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. They had to stay at the Holiday Inn for a while, as it took longer than expected for the Hisses to move out. When the Baughmans finally did move into the Hiss home, it turned out there was a problem. They hated it.

Here, says New College historian Furman Arthur, the power struggle that dominated New College’s first 27 months began. The Baughmans insisted the house needed $25,000 in repairs. They wanted a French Provincial look, with the teak painted white and a crystal chandelier in the dining room. Hiss, his beautiful house insulted, was no longer so enthusiastic about the new president. From then on it was a subtle form of war, a classic battle between the modernist dreamer and the French Provincial realist.

From Hiss’ point of view, things were clear. He was in charge of the school’s educational mission and architectural development. Baughman was in charge of administration, finance and fund raising. Hiss, the veteran of school board politics, was not above stacking committees and changing the bylaws. Finally, their myriad disagreements found a focus. When would the college open? Baughman said 1964, just as the board had promised. Hiss said this was impossible. There was no educational program, there was no campus. It had to be done right. No, said Baughman. It had to be done right now.

Hiss’ ideas for the college’s educational mission were extremely ambitious. “I am quite serious, and I believe totally realistic, when I say that the quality of teaching should be every bit as good as that at Harvard or Yale, Stanford or Duke. In fact, there is no reason it should not be better,” he said.

Time magazine called his vision “Ivy League among the Spanish moss.” In actuality, Hiss was inspired by what were thought of as the “experimental” colleges of the era, places like Antioch, Sarah Lawrence and Oberlin. He began to outline the innovations: The school year would be 11 months long, allowing students to graduate in three years. Independent study, honors programs and years-abroad were part of the program. Students received narrative evaluations instead of grades.

Hiss made it clear that it was not to be a “local college.” All students would have to meet its rigorous admissions standards. “There will be no place for mediocrity,” Hiss wrote.

In 1964, the charter class of 100 idealistic, brainy students from all over the country walked onto campus, greeted by professors—including Arnold Toynbee, the famous British historian—who were willing to take a risk on a brand-new college.

The possibilities for amazing architecture were in Hiss’ mind from the beginning. The chance to design an entire campus would appeal to the finest architects in the country, and Hiss contacted eight prestigious firms, including Louis Kahn, Eero Saarinen, John Warneke and I.M. Pei. They were all invited down for discussions. Pei was chosen for the first structure, a sort of academic center with meeting spaces and accommodations, not for students but for people here for seminars and meetings.

Hiss and Pei quickly became friends and began brainstorming what the campus should be. It was not going to be easy. One side of the property abutted the airport, the other side the bay, where there were several old, but beautiful Ringling mansions. The 110 acres zigged and zagged, and the town’s major highway split the campus in two. Some sort of brilliant solution was necessary. It has been said that Hiss and Pei were planning to tear down College Hall, the Beaux Arts mansion built by Charles Ringling, and build the campus on stilts out in the bay, connected by little bridges.

But the conflict between Hiss and Baughman deepened. Hiss wrote long letters to the trustees about their differences, stating that he and the college president were “at separate poles in our ambitions, in our goals and in our beliefs.” He felt that his vision of the college was being compromised, and he was right. The demands of fund raising, of hiring a dean and staff, and of coming up with a campus, even if temporary, were outrunning him. In a last-ditch effort to regain control of the situation, Hiss offered his resignation.

If he thought the trustees would rally around him, he was wrong. On Feb. 14, 1964, Hiss’ resignation was accepted and his involvement with New College ceased.

The Pei Residence Halls as they appear today.

Hiss moved to London not long after, where he lived for a while, traveling, taking up photography again. Then he moved to California, first to Carmel, then to Monterey, where he died in 1988. He wrote a famous article for Architectural Forum in 1967, bemoaning what had happened to Sarasota. Greedy developers had moved in, the young architects had for the most part moved on, conservative forces had gained control of the school board. New College was a shadow of what it could have been. The brief glorious moment was over.

But what happened to New College, now in its 61st year, both proved and disproved Hiss’ theories. Yes, the campus is a hodge-podge of disparate elements—its beauty, plan and architecture did not become what Hiss had hoped. Yet somehow, it has turned out to be exactly what Hiss dreamed up educationally. Idealistic, intellectually gifted students still plan their own course of study, grades are still nonexistent, experimentation is encouraged and the value of being an intellectual is still prized. The plan that he dreamt up in 1960 has flourished.

So has his legacy. The architectural style he championed has come to define the town. And so has his own personal style—tasteful, elegant, progressive, intellectual. Much of the cachet Sarasota enjoys in the eyes of the world can be traced back to him.

“He was an amazing, amazing man,” says Carl Abbott, the last of the Sarasota School architects still practicing.

“He loved Sarasota,” says his daughter Muffi. “He loved being a part of it.”

The town is finally loving him back. An exhibit, organized by the new organization Architecture Sarasota, and entitled The Vision of Philip Hiss, is currently on display at Architecture Sarasota, 265 S. Orange Ave., through April 11, 2022.

Many thanks to Architecture Sarasota for its help in preparing this article.