Sarasota Architect Replicates Iconic Paul Rudolph Structure

In 1952, when Walt Walker commissioned the young Sarasota architect Paul Rudolph to design a winter cottage on Sanibel Island, he surely knew that he would get a unique structure. But could he have imagined that the little house would become world-famous? Or that generations of architects and scholars would study it as one the most original works of midcentury architecture?

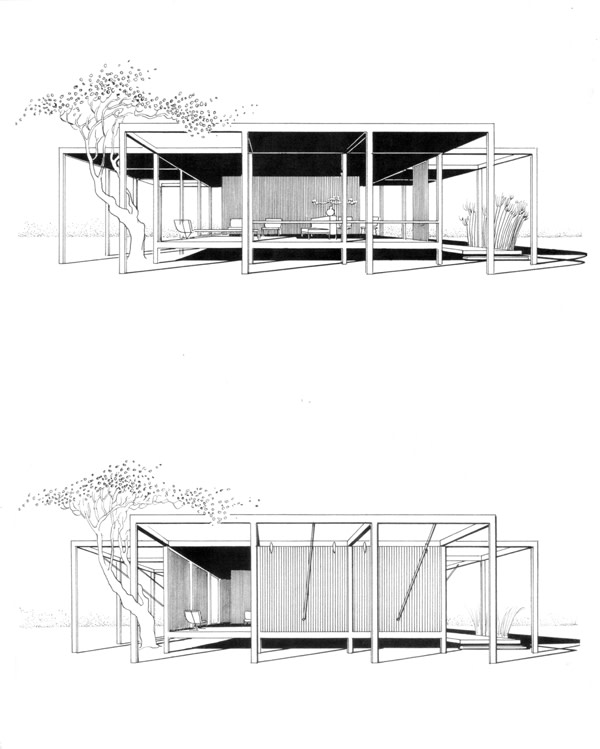

That all came true while Walker, far away from his cold native Minneapolis, lived in the house for 20 winters, enjoying the breezes and the feeling of an open-air pavilion when he raised the flaps, and a cozy cottage when he lowered them. Today the building is used as a guest house, and the Walker family continues to care for it. Because the house is private and in a fairly remote location, it’s been known mainly through Ezra Stoller’s wonderful photographs and Paul Rudolph’s renderings.

Recently, the Sarasota Architectural Foundation came up with the idea of building the Walker Guest House new—using Rudolph’s drawings and authentic materials—as an exhibit so anyone can visit and experience Rudolph’s great composition of flexible space. The exhibit is now installed on the grounds of the Ringling Museum and will open early next month and remain on exhibit until October 2016, eventually traveling around the country.

My construction team and I were charged with building the exhibit. What a challenge. And what a great opportunity to grapple with Rudolph’s ideas, design and technologies while building a temporary exhibit that can be taken apart, transported, and put back together at future venues.

It helped us to realize that every part of Rudolph’s design had a reason and purpose. More than any other architect of his generation, Paul Rudolph was able to combine historical knowledge, current ideas, extraordinary skills and natural talent to create works that were entirely new. As his friend Philip Johnson remarked, Rudolph was always admired for the speed of his mind.

So the little Walker Guest House is dense with meaning and intention, yet at the same time it’s physically light and delicate. Rudolph designed the house as white-painted wood frame construction to tap into the long tradition of such houses in the American South, where he grew up, with porches and a comfortable domestic feeling. But then, as an innovator, he stretched the capacities of wood to their limits. The outrigger columns, for example, are just 2x4s, unbraced, 10 feet long. As one might imagine, these columns sagged and twisted in the original structure and required reinforcing over the years.

We were committed to wood construction (though steel or aluminum would have been an obvious improvement) because we wanted the form of the exhibit to be as authentic to Rudolph’s intentions as possible. We ended up using laminated veneer lumber, milling it to 1950s’ 2-by-4 dimensions (1 5/8” by 3 5/8”) and applying bondo and wood filler, primer and paint, to give the rough structural members a finished surface.

Rudolph’s large hinged wood panels are the design’s most innovative element. When the flaps are down they function as walls, creating a closed box, and when open they become roofs for an extended porch. The occupant can adjust the flaps to any position in between, for breezes, shade and view.

Rudolph envisioned the flaps as a way to create dynamic architectural space, which he perceived as a fluid having both volume and velocity. By adjusting the flaps, the building and its space came into motion, and for Rudolph this could engender a rich perceptual and even emotional experience. He called this the psychology of space.

We built the flaps like large doors with wood framework and plywood skins. We wondered whether to apply wall paint or roofing material. (Is it a wall or a roof?) We chose white enamel paint everywhere inside and out to emphasize the abstraction of the form. We replicated Rudolph’s elaborate rigging system (Lt. Rudolph worked on ship construction during World War II), including crafting steel counterweights to match the originals’ size and weight, and using ropes faithful to the period. But we did reduce friction in the system by using ball bearing hinges and blocks. The flaps are much easier to use—and therefore better for experiencing the space—than in the original structure.

The Walker Guest House is designed on an 8-foot-by-8-foot grid, horizontally and vertically. This design of pure rationality and symmetry not only reflects Rudolph’s design discipline, it also acknowledges the role of history and Rudolph’s commitment to participating in the ongoing flow of architectural innovation. This was a radical position to espouse in 1952, as modernism purported to reject history (though it never really did). One can think of the four symmetrical outriggers/porches as a reinterpretation of the geometry and ordering principles of say, Andrea Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, which in turn represented a rediscovery of ancient architectural principles.

Today we can look to James Turrell’s Skyspace at The Ringling, where four-sided symmetry orients and grounds the visitor in a static environment, which then frames the continuous motion of the sky viewed above. At the Walker Guest House, Rudolph’s wood squares act as frames for the view of space in motion beyond; and better yet, you can actually walk through the frame and into the space.

The potential of the Walker Guest House as an architectural exhibit reminds me of Mies van der Rohe’s 1928 German Pavilion in Barcelona. It existed as an exhibit for a short time before it

was taken down, and then was known only through photographs for more than 50 years. It was rebuilt in the mid-1980s. I was fortunate enough to visit, and it helped inspire me to become an architect. I learned years later that Paul Rudolph also visited the rebuilt Barcelona Pavilion and it had a profound influence on him as well. I hope that, in turn, the Walker Guest House exhibit will inspire and influence visitors to think about how the art of architecture can affect and influence how they see and experience the world.

Joe King is a local architect and contractor. With Christopher Domin, he is co-author of Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses.